“Every neighbor had someone in the camps or ‘taken to study,’ as they call it.”

“…the worst thing was that you never knew when you would be let out.”

“I haven’t talked to my family because I was told not to contact them or else they would be sent to re-education.”

These are but a handful of the accounts in an August report published by Michelle Bachelet, the then-UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, describing egregious and widespread abuses by the Chinese government against Uyghurs and other Turkic communities in Xinjiang, western China.

The abuses may amount to crimes against humanity, “requiring urgent attention by the United Nations intergovernmental bodies and human rights system,” she said in the report.

China tried to block publication of the report, but it is important for other governments to give it the urgent attention it deserves and have the chance to discuss its findings in a UN setting.

Governments, including Kazakhstan, will decide if such a discussion is possible.

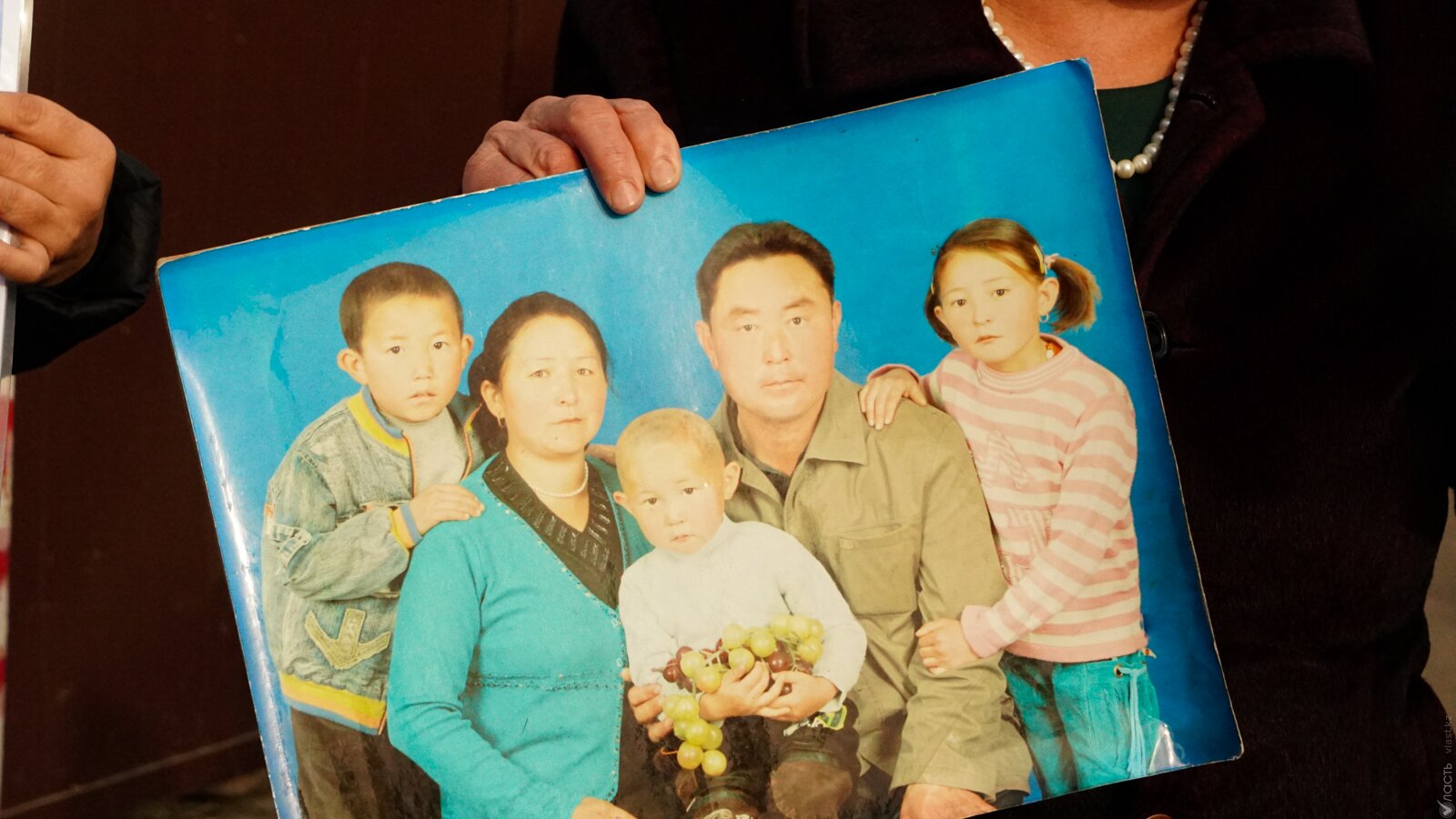

The situation in Xinjiang is important for Kazakhstan. Ethnic Kazakhs, including residents and citizens of Kazakhstan, have been among those who have been detained and abused in the detention camps across the border in China. In recent years many have fled to Kazakhstan and sought refuge there.

In early October the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) in Geneva, the top UN body handling human rights issues, will vote on a procedural motion proposing a discussion in the Council early next year of the UN’s Xinjiang report. Kazakhstan is currently a member of the Council and has an important voice on this issue. It is vitally important for Kazakhstan to help clear the way for open debate on this key human rights issue.

People quoted in the report described being held in mass arbitrary detention facilities for months—with no indication of how long they would be held or what conduct landed them there, and without contact with family members. They described beatings, being deprived of adequate food, and being forced to regularly take unidentified medication, which made them drowsy.

One woman described a forced gynecological examination performed in front of other people: it “made old women ashamed and young girls cry.” The majority of the people interviewed had been threatened by authorities not to tell anyone about their experiences.

The UN analysis also details the government’s deliberate misuse of “terrorism” and “extremism” legislation, in which authorities treat legitimate behavior—including wearing “irregular beards,” “having too many children,” or “resisting…sports activities such as football”— as aspects that can lead to arbitrary detention.

Since the publication of the report, the UN’s most authoritative assessment of human rights in Xinjiang, Beijing has rejected its contents, arguing it should not be discussed within the UN. It euphemistically refers to the abusive detention centers as “vocational education and training centers” – though it refused to produce a copy of any curriculum when asked by the UN rights office.

Kazakhstan seeks close and constructive relations with its neighbors as part of its multi-vector foreign policy. It has also said it is committed to upholding international human rights standards based on UN norms.

Kazakhstan should do its part to ensure that Bachelet’s report is debated at the Human Rights Council. It would show Kazakhstan’s support for the values of the United Nation, including the Council, at a time when those values are under threat. No human rights issue should be beyond discussion at the Council.

President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev himself knows the importance of mechanisms for international human rights, from his years working in Geneva as director-general of the United Nations office.

Kazakhstan has the chance to do the right thing regarding Xinjiang and international human rights. It should not let this opportunity pass.

Hugh Williamson is director, Europe & Central Asia division, Human Rights Watch.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.