At Vlast, since December 8, we received four letters from Roskomnadzor, the Russian agency responsible for censorship. The censor demands that we remove some of the news we published about the war that Russia waged on Ukraine. Vlast is not the first media in Kazakhstan to receive such demands, and obviously not the last.

Yet, many were surprised by this, as Roskomnadzor once again tried to “meddle into the affairs of a foreign country”. Which is exactly what happened, and not just yesterday and not only since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Even before the war, Russian authorities considered it possible to demand that media writing in Russian outside of Russia rewrote or deleted some of the materials. The excuse could be, for example, stories about suicide - as was the case for our Kyrgyz colleagues at Kloop.

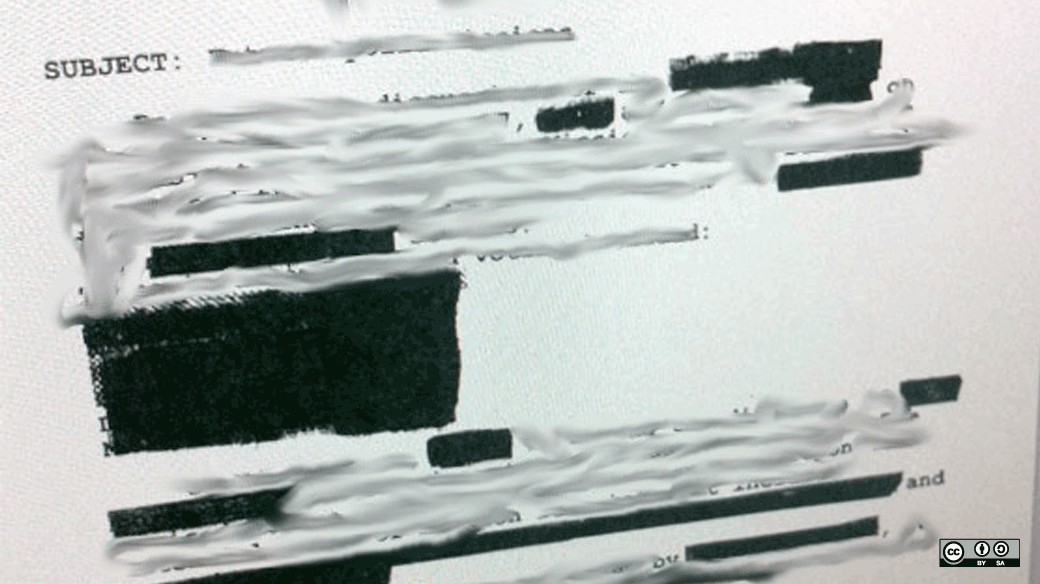

For many years and under various pretexts, Roskomnadzor effectively censored publications in Russian and foreign media. Outlets were required to change the wording when mentioning ISIS, to use certain definitions for drug trafficking, to avoid writing about methods of suicides, and so on. In Russia, the practice of media interference became massive.

Since the outbreak of the war, censorship within Russia reached a whole new level: Anyone who would not toe the line would be banned. Propaganda was on duty, day and night, from TV to newspapers to the internet, telling Russians that the war is not a war and Ukrainians are not people. The list of “foreign agents” has grown to phone book-size and an increasing number of websites have been blocked in Russia.

Should we then be surprised that Russian officials try to control what the media writes in Russian around the world? Of course not. Is it worth resisting these demands? Most certainly.

Kazakh media works for the Kazakh audience. We should not be concerned about what Russian officials, propagandists, or “military correspondents” think of us when they rush to their Telegram channels to react to our publications. For us, it is important to write for our audience, and mostly about our country. And when a neighboring country invades another, we call a spade a spade, without inventing new words.

The price to pay is not just that Kazakh media misses out on a marginal readership in Russia (in our case, it always floated between 5% and 10% and will now, obviously, disappear). The real cost is making sure that our readers have access to real news and do not only read reports churned out by the Russian propaganda machine, which still has full access to the Kazakh audience. And which keeps spreading hatred and justifying the war, without even calling it a war.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.