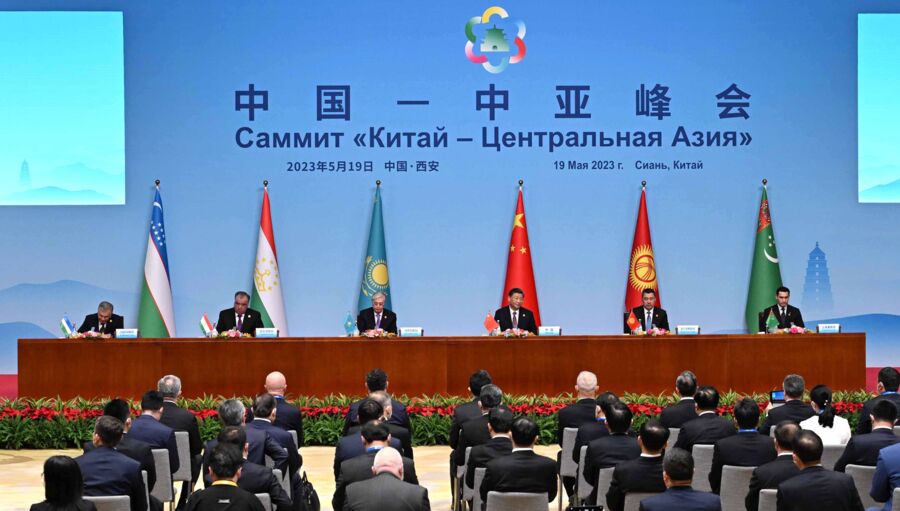

At a two-day summit, Chinese and Central Asian leaders met to discuss the future development of their cooperation, which China looks to strengthen via investment and institutional cooperation.

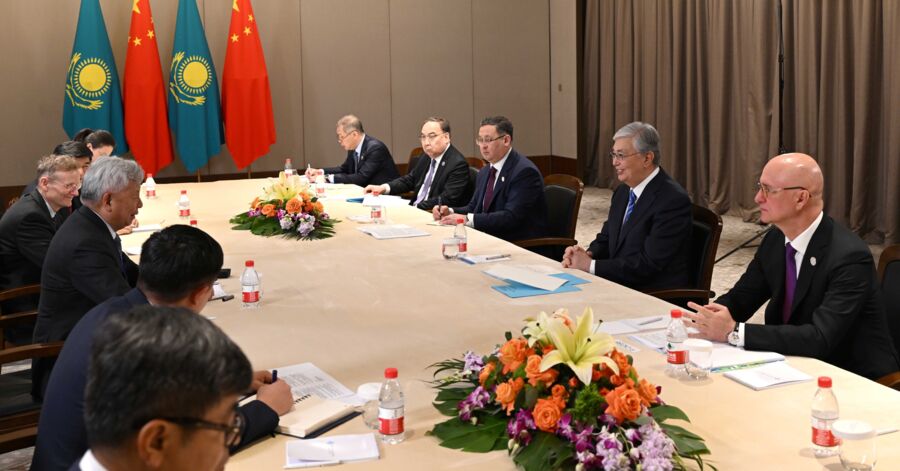

In the lead up to the summit, China’s President Xi Jinping met with some of his Central Asian counterparts on a bilateral basis, the typical format of China-Central Asia cooperation until recent years.

During these talks and the joint sessions on May 18 and 19, the participants announced the signing of deals and proposals that were already months in the making.

“This is an act of political pageantry, which China does very well,” Tristan Kenderdine, research director at political-risk consulting firm Future Risk, told Vlast.

Giulia Sciorati, postdoctoral fellow at the University of Trento, where she researches China-Central Asia relations, agreed that this event is more of the same.

“This event was bound to be grandiose, but I believe this is business as usual for China and Central Asian participants,” Sciorati told Vlast via phone from Astana.

In his keynote speech, Xi said that China and Central Asia “should fully unlock our potentials in traditional areas of cooperation such as economy, trade, industrial capacity, energy and transportation.”

In 2020, a Chinese initiative kick-started a 1+5 format for summits with the five Central Asian countries. After the inaugural two summits held virtually because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the meeting in Xian is the first in-person gathering of the kind.

Much Ado

China’s economic presence is already felt in Central Asia due to large-scale investments and infrastructure projects. Most of these initiatives stemmed out of the 2013 Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which Xi announced during a speech at Nazarbayev University in Astana.

Now, China’s new global policy looks to upgrade and renew their efforts in the neighborhood.

“The BRI has changed, but China’s approach to Central Asia remains much the same,” Kenderdine said. “The Global Development Initiative holds a more assertive focus on aspects of security and civilisation in the areas of international development, finance, and industry”.

When China makes a step towards a neighboring region, observers immediately prick up their ears and forecast a burgeoning influence from the economic superpower.

Ahead of the China-Central Asia summit, analysts said that the initiative signals an intention for China to substitute Russia’s hegemony on its former Soviet underbelly.

Experts said that the war in Ukraine accelerated the ongoing processes in the region, “the largest of which is China pushing out Russia as the largest hegemon in the region,” Bradley Jardine, managing director of the Washington-based think tank Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs, told Al Jazeera.

The thesis that China is actively pushing out Russia is contested in the expert community.

“I am skeptical that this sends any message to Russia, this seems more like a way for China to present a supportive image to the region,” Sciorati said.

Silk Road Symbols

The leaders met in Xian, the capital of Shaanxi, a province in central China. Always meticulous in their choices, Chinese diplomats selected Xian because of its historical role as a departure point for the ancient Silk Road connection between imperial China and the Central Asian realms.

This narrative about Xian’s symbolism on the surface masks a concrete reason for the choice of the city, says Kenderdine.

“Had it been purely symbolic, then the natural choice would have been Lanzhou, the traditional gateway to the Silk Road at the China side of the Gansu corridor. The choice of Xian is much more closely related to industrial and logistics integration. Almost all Central Asian exports to China must pass through Xian”.

Beyond the symbolism of the location, however, analysts found little novelties in the announcements made.

“For China to announce a new project, new policy, new bilateral agreement would mean that that process had effectively been completed. The announced ‘opening’ of the third rail crossing? It has been operational since 2021,” said Kenderdine of Future Risk.

Brotherly Relations

In his speech, Xi quoted a Central Asian proverb, saying that “Brotherhood is more precious than any treasure,” emphasizing the need to cooperate among brotherly nations.

China and Central Asia boast a growing trade turnover, which reached $70 billion last year. Kazakhstan accounted for the lion’s share, with around $31 billion.

Albert Park, chief economist at the Asian Development Bank in Beijing, told Reuters that their goal is to support initiatives that reduce trade barriers and harmonize trading standards, and, importantly, “more forums where government officials can talk and try to develop standards to promote more trade”.

Some of the more concrete deals that were announced within the framework of the renewed cooperation concerned Kazakhstan.

State holding Samruk-Kazyna said in a press release that the capacity of the oil pipeline linking Kazakhstan to China will be almost doubled to 20 million tons per year at a cost of $200 million. State-owned Kazmunaigas and China’s CNPC co-own the pipeline.

At the summit, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev endorsed a plan to make Khorgos, the dry port at the Kazakh-Chinese border, a food trading and distribution hub. On the same day, he attended the ceremony for the construction of a “Kazakhstan Logistics Center” at the dry port of Xian.

“Agricultural exports from Central Asia to China are a key ingredient in the BRI, and clearly beneficial to both China and its partner countries. Yet, the seeming ‘win-win’ potential here has mostly remained unrealized,” Kenderdine argued.

Differently from Western diplomacies or the Kremlin, China’s plans for Central Asia seem to span decades, if not centuries, according to Kenderdine.

“This summit is another step in a long road. Not necessarily important for what might happen over this week, but what the institutionalization of these relationships may mean over the longer-term,” he told Vlast.

Constant Repression

In 2016, thousands of people protested across Kazakhstan against proposed amendments to the Land Code, which they said would have granted increased access to Chinese nationals into their territory. Conspiracy theories about the country’s leadership having “sold chunks of land to the Chinese” are widespread among the population. The protesters, one thousand of which had gathered in Atyrau, thousands of kilometers west of the Chinese border, dispersed peacefully, but the topic remained in the nationalist political agenda.

At the height of the Chinese government’s repression of the Muslim population in Xinjiang, the autonomous region across the border, people in Kazakhstan questioned the policy allegedly aimed to “re-educate” certain strata of potentially-extremist population. When information about “re-education camps” where the Chinese government kept tens of thousands of people without their consent, Kazakhstanis started protesting publicly the treatment of their brethren, some of whom held Kazakhstani passports.

Nowadays, a number of people has been gathering outside the Chinese consulate in Almaty almost daily, to ask about the fate of their relatives, who are believed to be detained in the camps. The police often asks them to disperse and sometimes prevents journalists from covering the protests.

When Nagyz Atajurt Volunteers, a civic association that has repeatedly tried, without success, to register as a party, applied to hold a public protest on the first day of the China-Central Asia summit, the local authorities did not allow it. On May 17, in an effort to prevent a possible unsanctioned rally, the police detained Nagyz Atajurt’s leader, Bekzat Maksutkhanuly, for a 15-day administrative arrest.

Kazakhstan’s government policy seems to be focused on nipping in the bud any sign of dissent against China.

And it has done so also with the help of Chinese technology and institutional cooperation.

“Security integration is really advanced between China and the Central Asian states,” said Kenderdine. “The connection among security apparatuses demonstrates the importance placed on Central Asia, as an extension of China’s domestic security policy from Xinjiang into its neighbors. China’s security integration with Central Asia looks very different to anything seen in the Pacific or Indian Ocean.”

In October 2013, Xi chose Kazakhstan’s capital Astana to announce the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative, which led to hundreds of billions of dollars in investments across the globe, especially in infrastructure and industrial facilities.

Ten years later, the Xian summit played the role of yet another geopolitical prism through which both existing and future cooperation will be analyzed.

Sciorati said that this framework of cooperation demonstrates China’s maturity in its approach to Central Asia.

“China's first interactions with the region were often filtered through Russia's mediation. Even with joint initiatives like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. The BRI has shown China's willingness to be more autonomous in developing ties with its Central Asian neighbors,” Sciorati said.

A few days before, the Central Asian leaders had traveled to Moscow to attend the Victory Day parade hosted by their Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin. The May 9 event focused on Putin’s effort to show that his former Soviet allies still support him, despite the ongoing war in Ukraine. But it was also an occasion to hold a joint talk about Russia-Central Asia relations.

While it is hardly a zero-sum game, as Russia and China do not seem in an open competition for Central Asia’s attention, it is clear that by institutionalizing regional talks China is treating Central Asia as a reliable trading partner. Through increased economic and infrastructure ties, China’s influence in the region is growing.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.