The latest trend in Kazakhstan’s attempt to project its relevance in international relations is the self-portrayal as a “middle power.” It is doing so through official channels, whether via the work of its embassies abroad, or via opinion pieces in government-friendly media outlets.

During a visit to Kazakhstan on August 1, European Commission Special Representative Josep Borrell repeated the “middle” refrain and reportedly said: “Kazakhstan used to be [considered to be] in the middle of nowhere. Now it is in the middle of everywhere.”

The upcoming conference at the annual Astana International Forum is titled: “Middle Powers in a Changing Global Order.”

When the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) published a report on “middle powers” on January 23, the government outlet The Astana Times jumped on the topic by writing a celebratory piece that announced that “Kazakhstan [had] secured a place among the world’s middle powers for the first time.”

In a piece published (evidently without editing) at the end of May at Euronews, Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev argued that “middle powers have the power to save multilateralism”.

In his article, Tokayev said the current global crises need “multilateral solutions” because “the traditional powerhouses are increasingly unable to work together.”

It is the role of middle powers, according to Tokayev, “to ensure greater stability, peace and development in their regions and beyond,” thanks to “economic strength, military capabilities, and, perhaps more importantly, political will and diplomatic acumen.”

Roman Vassilenko, deputy foreign minister, told Euractiv in February that “we need more robust multilateralism, [and] this responsibility [now falls] on a broader range of international players.”

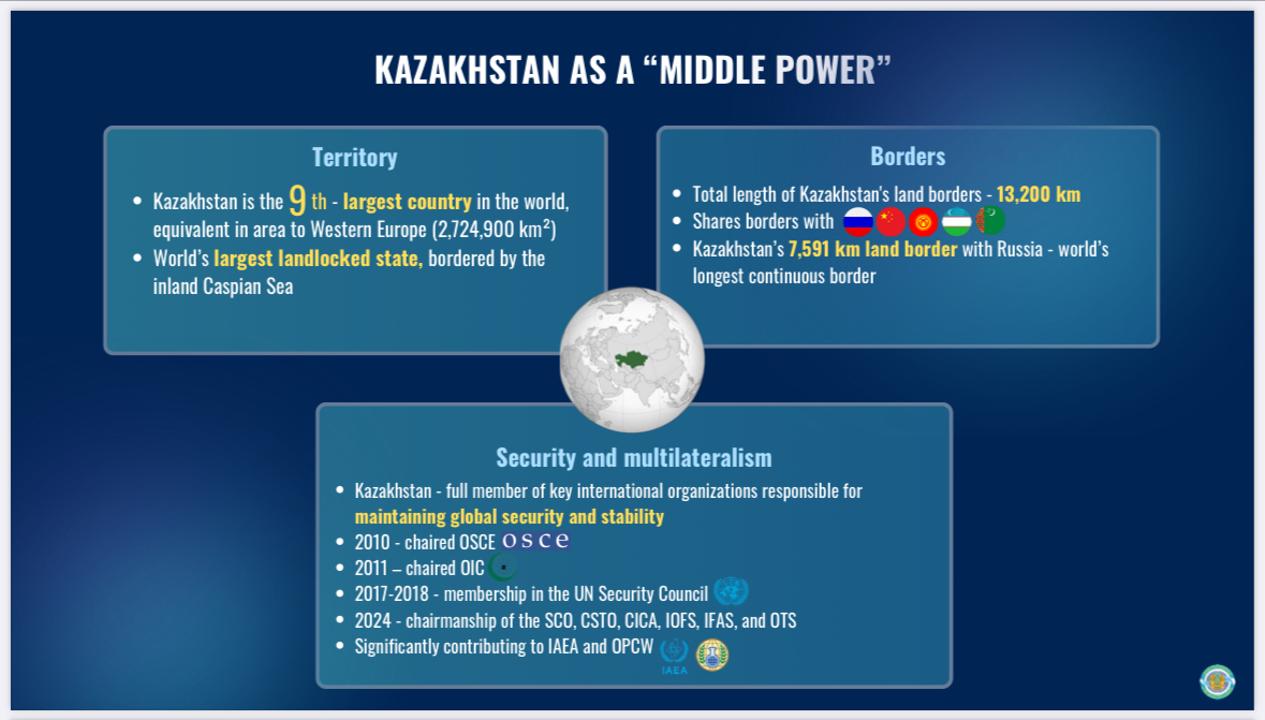

In June, Madi Atamkulov, Kazakhstan’s ambassador to Serbia, held a lecture titled “Kazakhstan as a Middle Power” in Belgrade. Kazakhstan’s embassy in Canada published in May a web page of general statistical indicators (country size, population, GDP, among others) titled “Kazakhstan as a Middle Power,” almost pandering to the algorithm.

In a piece for Modern Diplomacy entitled “From Backwater to Beacon: Kazakhstan’s Identity as a Middle Power”, Miras Zhiyenbayev, a foreign policy expert at a think tank within the Maqsut Narikbayev University in Astana, listed several achievements and focuses solely on Tokayev’s role in building such a “middle power” profile for Kazakhstan.

Notably, Modern Diplomacy’s advisory board features former ambassador to the US Yerzhan Kazykhanov, deputy head of the Presidential Administration since January 2022.

These few examples are part of a concerted effort by the government to build a new image for Kazakhstan’s foreign policy, though this changes little in Kazakhstan’s quest for visibility on the global stage, which started under former President Nursultan Nazarbayev.

In an interview with Vlast, Nargis Kassenova, director of the Central Asia program at Harvard University’s Davis Center, said that vanity played a big role under Nazarbayev.

“Kazakhstan considers itself as a ‘good citizen’ in international relations, focusing on cooperation and a progressive international agenda. There was definitely a vanity element about it during the Nazarbayev times, when the efforts to make Kazakhstan more important, relevant, and central in global affairs were carried out to please him,” Kassenova said.

This led to an excessive use of resources towards these goals, said Kassenova. “Resources that could be used for other purposes for society.”

A Tiny Shift, but a Shift Nonetheless

In a piece praising Tokayev’s reforms, Jamestown Foundation’s Janusz Bugajski wrote that “Central Asia was once on the periphery of Western diplomatic priorities,” while Asia Society’s Genevieve Donnellon-May wrote in February that at independence, “a little over 30 years ago [Kazakhstan] played an unassuming role in international relations.”

Both of these articles consider Tokayev’s policies to portray Kazakhstan as a middle power a success. Other academics disagree, calling into question the real extent of the role of middle powers as well as the magnitude of the shift in Kazakhstan foreign policy since the power transition in 2019.

Filippo Costa Buranelli, senior lecturer in International Relations at the University of St. Andrews, argued that Nazarbayev set a tone that was highly personalized.

“Nazarbayev focused on internationalism in an effort to be accepted as a reliable actor and a legitimate UN member. This approach, centered around his figure, also helped him consolidate power domestically,” Costa Buranelli told Vlast in an interview.

A screenshot of Nazarbayev's congratulatory remarks in 2016 after Kazakhstan's bid for a temporary seat at the UN Security Council was accepted. Source: Akorda.kz

Luca Anceschi, professor of Eurasian Studies at the University of Glasgow, sees more continuity than change in Kazakhstan’s foreign policy.

“I don’t see a substantial change in Kazakhstan’s foreign policy since the changing of the guard. Nazarbayev’s foreign policy aimed to grow Kazakhstan’s international stature just by announcing it. And at the time, Tokayev was the executor of Nazarbayev’s foreign policy,” Anceschi argued.

Tokayev served as prime minister, foreign minister (twice), and Senate speaker (twice) during Nazarbayev’s three decade-long reign. He also held the position of Deputy Secretary-General of the UN (2011-2013).

Anastassiya Reshetnyak, a foreign policy and security expert at the Astana-based think tank Paperlab, said that Tokayev was a “man of the system” under Nazarbayev and thus influenced foreign policy within the general guidelines of the government.

“In the early 2010s, for example, we studied Kazakhstan’s diplomacy in Tokayev's books,” Reshetnyak told Vlast.

Then-President Nazarbayev meeting with Tokayev, then-Deputy Secretary General of the UN, in November 2012. Photo: Akorda.kz

A New-Old Policy

Kazakhstan achieved its most notable foreign policy success during the twilight of Nazarbayev’s tenure, according to Reshetnyak.

“The peak in the image-making efforts of Kazakhstan was its non-permanent membership in the UN Security Council in 2017-2018. At the time, Kazakhstan proposed initiatives on global peacebuilding, through which it could draw the attention of the world community towards regional problems in Central Asia,” Reshetnyak said.

In 2017, Kazakhstan also hosted a specialized EXPO in Astana. Pleading to Nazarbayev’s vanity, in 2013 the country also bid, unsuccessfully, to host the World Petroleum Congress in 2017. To the disappointment of Kazakhstan’s diplomats and energy elites, the Congress was assigned to Istanbul. The snub on the oil front, however, paled in comparison to Nazarbayev’s attempt to enshrine his name in global politics by bidding for the Nobel Peace Prize, also in 2017 (a repeat of several fumbled attempts to nominate Nazarbayev by the Assembly of People of Kazakhstan in 2006, by two US congressmen in 2008, and the World Assembly of Turkic People in 2010).

Since coming to power in 2019, Tokayev has ridden the wave of the old regime’s foreign policy.

“Immediately after the power transition, we saw unsuccessful attempts to cash in on Nazarbayev’s potential. Such initiatives include, for example, a statement about Kazakhstan’s potential to stabilize the situation in Afghanistan after the Taliban seized power in 2021, as well as Nazarbayev’s offer to mediate between [Russia’s President Vladimir] Putin and [Ukraine’s President Volodymyr] Zelenskyy,” Reshetnyak said.

Costa Buranelli argued that results are not as crucial in the newly-found middle power paradigm as the process itself.

“Kazakhstan’s efforts are mostly aimed at creating platforms for dialogue, rather than necessarily achieving immediate results,” Costa Buranelli said. “This is a rather smart approach because it entails low risks, but potentially high returns: Kazakhstan does not in fact claim the role of mediator - who shares a responsibility towards the outcome - and only reaps the benefits if the negotiations are successful. Should they fail, at least Kazakhstan offered a credible platform.”

Kassenova agreed: “The key is that the label ‘middle power’ doesn’t come with any kind of requirement.”

The continuation of a responsibility-free foreign policy, according to Anceschi, signals the unwillingness to take the decisive step to throw Kazakhstan into the ring of relevant international players.

“Kazakhstan has an extensive diplomatic tradition at this point. It also has spent serious budget money in training its diplomatic cadre and has spent a lot of effort in outreach. It should be high time for Kazakhstan to move from its ‘teenage years’ into adulthood, diplomatically,” Anceschi said.

“Despite possessing the most sophisticated array of foreign policy tools in the region, Kazakhstan has not made the jump from declaration to action, from representation to reality,” Ansceschi argued.

A Vintage Concept

In the academic world, the Middle Power concept seems now surpassed by more sophisticated theories. It was born as a response to the idea that the world was divided between Great Powers and the rest. This trend gave rise to a theorization of both Australia and Canada as “middle powers” after World War II. The two governments exploited the concept, which set them apart from “the rest” and could help “secure [their] country’s national interest in a new world order”

Despite a general lack of agreement in terms of definitions for both academics and practitioners, “middle powers” can be defined as the countries that can influence certain sectors and regions in international affairs, or that can “behave” like a Middle Power, or that rank in the middle according to their capabilities.

The latter is the definition applied by Olivier Arifon, a French professor, who presented his preliminary research in June in Almaty on Kazakhstan’s public policy as a Middle Power saying: “If you look at where Kazakhstan is across several global rankings, you’ll find that it’s often in the middle!”

Such a shallow analysis, however, provides little evidence that the concept of Middle Power is anything more than a nation-branding tool.

In their 2023 academic analysis of the concept of Middle Power, published by the prestigious journal International Theory, Jeffrey Robertson and Andrew Carr argued that “middle power theory no longer helps us distinguish or interpret these states.” In their research on Canada, Australia, South Korea, Indonesia, Turkey, and Mexico, Robertson and Carr conclude that the concept “lost real-world application”.

Last year, academics Stephen Nagy and Jonathan Ping, wrote that “the heyday of normative middle power diplomacy is on life support and possibly even dead.”

Focusing on the Neighbors

Kazakhstan has tried to use the newfound Middle Power tool to boost its international image. And it seems to have worked, to a certain extent.

“While there are certainly overpitched elements of this ‘middle power’ image, it looks like this strategy of self promotion is working. It tells the big power, from East to West, that Kazakhstan is not just a land of transit and resources, but has agency in global affairs. This is definitely a rebuke of the Great Game narrative,” Costa Buranelli said.

Reshetnyak agreed: “In order not to look like a ‘pawn’ in the game of the great powers, Kazakhstan chose the role of a relatively independent mediator.”

In highlighting the efforts Kazakhstan has made to distance itself from Russia, Robertson argued last year that “to impact a great power, a middle power does not need to switch sides, it just needs to indicate that the great power no longer has its support.”

The government’s diplomatic decisions since the February 2022 Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine gave Robertson the impression that this impact was being felt and could continue to be relevant.

“Kazakhstan’s relevance lies less in how it fits the academic category [of Middle Power], and more in how it practices the role,” Robertson wrote in a piece for the Australian think tank The Lowy Institute.

Talking to Vlast, Kassenova said this is the niche that Kazakhstan can carve for itself.

“Kazakhstan has the resources and the capacity to do more, and can try to create new coalitions and partnerships. When there are growing divisions at the top, you can make up for it by creating solidarity networks among middle powers,” Kassenova said.

Diplomatic Snubs

Without tangible results, however, Kazakhstan’s attempts to sculpt its own image as a reliable diplomatic facilitator has routinely been put to question.

According to Reshetnyak, Kazakhstan lacks the “willingness to accept responsibility,” a crucial aspect of its Middle Power ambition.

Anceschi points to the absence of a proactive attitude beyond the organization of meetings, such as the Astana Talks on Syria or this year’s meeting in Almaty between representatives of Armenia and Azerbaijan.

“When one introduces themselves as a ‘middle power’, this presupposes an active approach. Which of the many conflicts around the world has it helped solve concretely? A change in rhetoric without concrete steps is not enough to turn Kazakhstan into a credible diplomatic platform,” Anceschi argued.

Kassenova pointed to the shift from Nazarbayev’s ambition to become recognized by the bigger powers - such as with the bid for the OSCE chairmanship in 2010 - and today’s diplomatic plans, which do not include promises in terms of democratic progress.

“The chairmanship of the OSCE is a prime example of a project driven by vanity, for which Kazakhstan took commitments and then failed at keeping them. Now, it’s less dangerous, because there are fewer commitments in promoting democracy, rule of law, and human rights [in Kazakhstan’s foreign policy],” Kassenova said.

Bolstering Kazakhstan’s own profile as a reliable trade partner remains one of the main objectives, it seems.

“It’s important for Kazakhstan to be taken seriously and attract more attention and investment,” Kassenova said.

Kazakhstan’s ambition could also get in the way of the unwritten rule of Central Asian diplomacy, by which none of the neighbors plays the role of the protagonist, argued Costa Buranelli.

“Relations in the region since independence have hinged on the principle that none of the neighbors should claim to be a ‘big brother’ to the others. Recently, however, there have been some concerns in the region that Kazakhstan is trying to steal the show and become a protagonist,” Costa Buranelli told Vlast.

While relations with Uzbekistan, the other regional power with diplomatic ambitions, have gradually improved, Kazakhstan seems to have learned from Chinese diplomatic conventions in terms of treating its regional partners with respect, despite their limited experience in international platforms, Kassenova argued.

“The Chinese leadership has been really effective in making smaller powers feel more like important actors in the global stage. There are certain aspects of diplomatic culture that Kazakhstan is taking from the Chinese [rulebook]. It’s a very subtle difference from the Russia-dominated Soviet past, but it’s a noticeable change in narrative, rhetoric, and ceremonies.”

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.