After the start of the war in Ukraine, Russian media and Telegram channels broadcast fake news regarding the actions of Kazakhstan’s government and about Kazakhstanis’ attitude towards Russians. Reached by Vlast, experts highlighted issues concerning access to propaganda channels and Kazakhstan’s potential counter-strategies.

Disinformation Flow

In May, Russian TV presenter Tigran Keosayan threatened Kazakhstan during a broadcast, after criticizing the government for not holding a Victory Day parade. Keosayan was later declared persona non grata in Kazakhstan.

Speaking at a panel at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum in June, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev drew attention to the inappropriate statements circulating in Russian media. Margarita Simonyan, director of Russia Today and Keosayan’s wife, who moderated the panel, quipped: “I even know who you are talking about.”

On August 20, Daria Dugina, a Russian propagandist who repeatedly expressed support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, was killed in a car bomb attack near Moscow. Two days later, Russian authorities accused a Ukrainian woman, allegedly holding a Kazakhstani passport and driving a car with Kazakhstani plates, of the murder. Kazakhstan’s ministry of internal affairs swiftly denied the statement.

On October 4, the Russian ministry of foreign affairs summoned Yermek Kosherbayev, Kazakhstan’s ambassador to Moscow, complaining that Ukraine’s ambassador to Kazakhstan Pyotr Vrublevsky had not yet been expelled from the country. In an interview in August, Vrublevsky said that the Ukrainian forces had set out to “kill as many Russians as possible.” In September, Vrublevsky had left Astana on a flight to Kyiv, a move that many read as his quiet exit. Vrublevsky, however, reappeared in his diplomatic capacity weeks later, enraging the Russian authorities. On October 5, Kazakhstan’s ministry of foreign affairs announced that Vrublevsky would no longer serve as the Ukrainian ambassador in Astana.

These are just a few of the many instances of pressure, disinformation, and threats that Kazakhstan has had to withstand since the start of the war.

A Media Literacy Problem

Media freedom watchdog Internews surveyed Kazakhstan’s media consumers in 2019 and in 2021, and found that most respondents obtain their news from social media and internet sources, while only 30% keep up-to-date through TV broadcasts. The survey showed that social media consumption is on the rise, while TV use has decreased sharply in the country, as it only remains popular among older strata of the population.

MISK, the Youth Information Service of Kazakhstan, a media literacy NGO, surveyed disinformation among the Kazakhstani public in 2022, finding that users seldom double-check the information they read on social media. Around 60% say they are sure they have never seen fake news.

Shalkar Nurseitov, a political analyst, believes that information warfare is key to the Kremlin’s foreign policy. “Through their propaganda, autocrats try to convince people that ‘foreign agents’ are the fifth column of external enemies that are trying to prevent the development of their country. With Russia, we saw it clearly in 2014 after the occupation of Crimea and we see it again now.”

Dimash Alzhanov, a political analyst who traveled to Ukraine in the summer, argued that Russian propaganda is designed to polarize the population. “Almost all the TV and internet providers in Kazakhstan offer Russian channels in their packages. This has become a very dangerous tool in the hands of the Kremlin. And that is in addition to our own lack of freedom of speech and the spreading of propaganda from our own government.”

According to Alzhanov, the Russian propaganda machine has also spelled out its messages through political parties. “We have already heard pro-Russian rhetoric from the People’s Party, which is completely controlled by Akorda.”

In the same vein, Nurseitov argued that the government should counteract this trend.

“It’s high time that Kazakhstan’s authorities come up with a counter-strategy, because there might be an increase in people who, by being exposed to Russian media, would espouse a pro-Russian position. We need to improve the quality of our journalism and promote independent media. Our citizens sometimes don’t even realize that they are victims of propaganda,” Nurseitov said.

A Language Issue

Serik Beisembayev, a sociologist at the think-tank Paper Lab, said that the number of Kazakhstanis exposed to Russian media could decrease as a result of the war in Ukraine.

“Since independence, the Russian-language media space has survived, but we saw that in the past couple of years the situation has started to change,” Beisembayev said.

Alzhanov stated that alongside the expansion of the role of Kazakh language, a bilingual society would be better suited to have an informed exchange of information and to foster political freedom. “Our only options to counter the lack of freedom of speech in Russia are to ban Russian propaganda outlets and simultaneously demand press freedom here in Kazakhstan.”

Several countries in the ex-Soviet space have been the target of Russian propaganda and Beisembayev argues that Ukraine is a good example of a country that has resisted effectively.

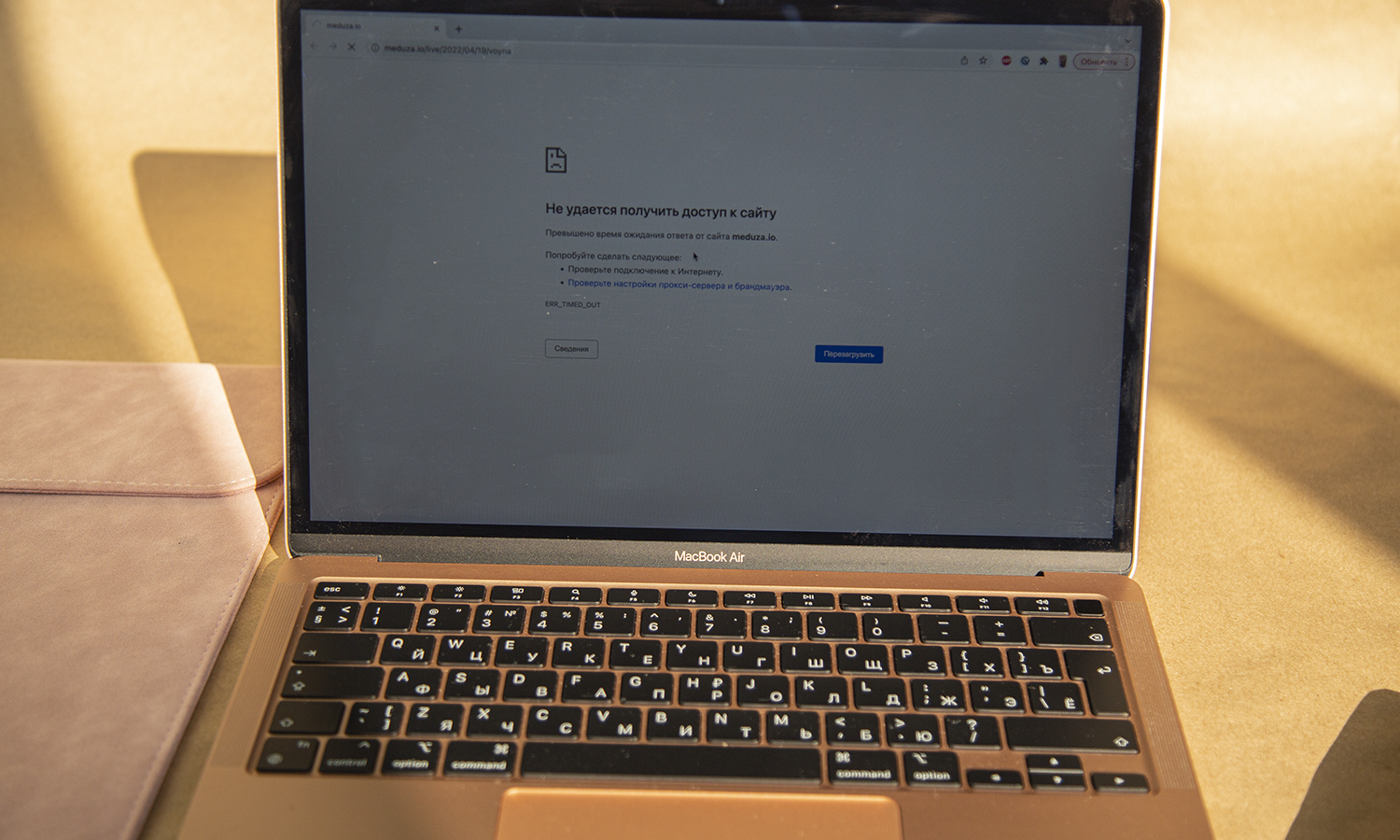

Shutting down Russian TV and blocking Russian websites, however, might not be a wise strategy, Beisembayev argues.

“It is impossible to keep these outlets at the door. YouTube and Telegram channels would still broadcast propaganda. We need to strengthen our own media space.”

Nurseitov said that the influence of Russian propaganda can only spread because there are too few independent media outlets in the country, who publish fact-checked information in Russian and Kazakh. Threats to freedom of the press, together with low levels of media literacy, expose the public to propaganda in both languages.

“In Kazakhstan, most people can easily access Russian media, which spreads the Kremlin’s propaganda. This is a problem, because some believe the propaganda. The fact that the Russian language is still widespread exposes many to misinformation from across the border.”

In addition, the country’s bilingual heritage leads most to seek information in Russian, according to Beisembayev.

“If we look at the analytics, people who are bilingual tend to look for materials in Russian, simply because the offer is wider. As the Kazakh-speaking proportion of the population grows, Russian propaganda might lose its influence in the future.”

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.