- ВКонтакте

- РћРТвЂВВВВВВВВнокласснРСвЂВВВВВВВВРєРСвЂВВВВВВВВ

Erden Zikibay, an artist, activist, and ally of the HeForShe Central Asia gender equality movement, for Vlast.

When I returned to Almaty after studying abroad, I initially had the impression that there was no catcalling in the city, such as street harassment expressed in whistling, car honks, lewd jokes, and indecent compliments. In large US cities, this is quite widespread, and there is a loud public campaign against it. And yet, the women I know in Kazakhstan told me that this happens constantly to them. The truth was that my presence had hindered catcalling towards the women that I accompanied. When men enter any space, they change the context. Men can use their privileges and support women with their words or even just their presence. When a man speaks out against sexism, other men are more likely to take his words seriously. On the other hand, our masculinity has “blind spots.” When discussing women, men cannot judge based on themselves and their experiences. We simply do not experience what they face. Men should just listen to women and believe them.

Many men fail to consciously perceive themselves as privileged. People in dominant groups often cannot see their advantages: Unearned privileges are invisible to those who benefit from them. Just as the sighted cannot grasp the experience of the blind and people without disabilities cannot understand those with special needs.

Canadian activist Janaya Khan formulated it this way: “Privilege isn't about what you've gone through; it's about what you haven't had to go through.”

As a man, what do you experience when a woman walks towards you as you are going down the street at night? Anything but fear. Ask a woman and she will probably answer with worries and fear.

A comparison with the animal world can be useful. Our ancestors passed to us the fear of spiders and snakes. But the number of dangerous spiders and snakes is anything but massive: around 10-15% of all snakes are poisonous, and the share of spiders that can harm humans is even smaller. That is, not every spider or snake you encounter will be poisonous, but why would you take the risk?

Men have a similarly bad reputation. Every man is part of a group that has historically posed a threat to women. And this imposes a moral responsibility on every man, whether he wants it or not. Sure, “not all men are oppressors and abusers.” But practically all women have experienced gender discrimination and violence in one form or another. And if we deny this, we betray women.

We can split men into two categories: A silent majority of “good men” and a loud minority of “bad men”, that is abusers, rapists, murderers. Many will say, “I’m not sexist, I’m not a rapist,” as if this were an issue about personal qualities and not about systems and structures.

More than once I caught myself allowing sexist words, phrases, or jokes to be heard without a reprimand. Men much older than me made fun of their spouses, sometimes even in front of them, and I thought it was not my place to stand up to them, so I awkwardly smiled and kept quiet.

But this silence is not neutral, it is also a position. Silence in response to discrimination is a sign of agreement with that discrimination. In the West, the slogan “silence is violence” means that inaction or indifference to any kind of violence against oppressed groups is equivalent to violence against those same groups. The German psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers believed that Germans who committed war crimes in World War II were guilty “morally”, and those who tolerated and did not resist them were guilty “politically”, thereby placing collective guilt on all.

Why are so many of the “good” men silent when women are hurt, either physically or verbally? How will we go down in history – as silent participants or active allies? Men are raised to be brave and defend the weak, but I believe that authentic male bravery is not silently going along with the flow of patriarchy and sexism but going against the current.

The main trap of the patriarchy is self-doubt and fear. Fear that you will be attacked, beaten, robbed, raped and/or killed. Patriarchy exploits these complexes and fears, offering people a simple model: The weak are beaten, therefore you need to be strong and strike first.

Many traditionally masculine men also view women as helpless, whom they need to defend from “bad” men. However, in most cases, violence against women comes from their intimate partners, who should be defending them.

When conversations center the prevention of violence against women, there is a demand to tighten laws, criminalize domestic violence, and more strictly sentence abusers. However, there are few who are ready to reconsider their own views on how boys are raised and relationships with men in general. For example, do not teach children that problems need to be solved with aggression and violence. Do not shame a man when he experiences hurt, disappointment, tears, fear, vulnerability and shares his worries. It seems that it is easier for society to endure sexists and find ways to appease them than to genuinely respect the rights of women.

Many seem to welcome such half-measures as women-only taxis and women-only carriages. However, I believe that this will lead to greater gender segregation, which, in turn, will inevitably reinforce the idea that women and men are different at their core and, therefore, cannot be equals.

Men are raised from birth to use violence, conquer, and if necessary, to kill. If we raise a boy from birth as a potential oppressor and rapist, how can we complain when he, having become a man, beats, rapes, and kills someone?

In fact, violence is not a strength, but a weakness. According to Leon F. Seltzer, the demonstration of force through anger signifies a lack of inner strength, resilience, self-confidence, or self-acceptance, an inability to maintain mental and emotional balance in the face of perceived difficulties. Anger is the ultimate bluff.

Behind the roaring external lion, there might be a frightened, trembling inner kitten. Seltzer believes that authentic strength lies in such qualities as patience, tolerance, compassion, strength of spirit, acceptance, and forgiveness. Many of these qualities are traditionally considered feminine qualities.

If every society will cultivate exactly these qualities, then the level of violence would inevitably wane. Without violence, the traditional patriarchy will not persist, because there will no longer be a need for “defenders,” and ossified gender roles will lose meaning.

In an ideal feminist world, there would be no war. Feminism is a kind of vaccination against violence, and collective immunity will develop when a significant part of humanity is vaccinated.

In Kazakhstan, many people carry the painful experience of centuries of occupation and colonization in their bodies, not to mention the terrible years of Stalinism. In addition, many Kazakhs feel deep pain and anxiety about demographics. I believe that this is a painful reaction to tragic historical events when the ethnicity was existentially reduced as a result of the man-made mass famine in the early 20th century.

Due to these historical traumas, the Kazakh society is undergoing re-traditionalization and idealization of its pre-colonial history. This, by the way, was an era when the value of Kazakh women was literally half that of men (in customary law, the ransom for killing a man was set at 1000 sheep, while for a woman, it was 500).

Today’s attempts by traditionalists to control women and their resistance to globalization and novelty are, in many ways, symptoms of colonial and totalitarian fears of losing freedom and independence once again, losing their identity, and becoming helpless victims of violence and terror. We cannot continue to deny, ignore or undervalue collective suffering, complexes and fears; we must accept and overcome them with a sense of love and compassion. Without this difficult collective work, we will forever remain hostages of our past and generational traumas.

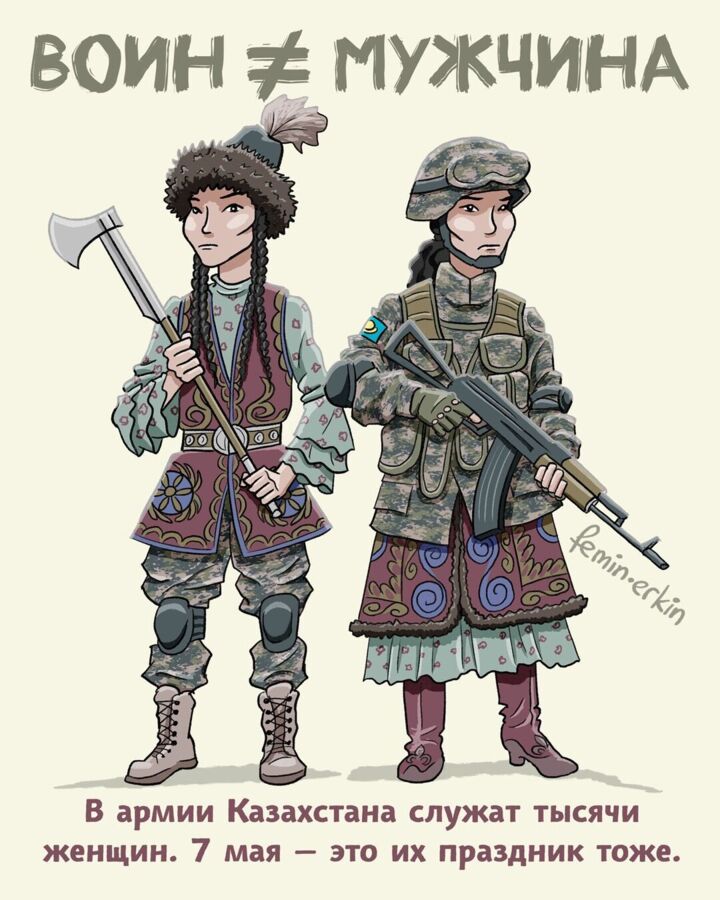

Feminism has a place in Kazakh society. It is possible to unite useful traditions and modern knowledge in one’s identity. A Kazakh woman can be the head of a company and breadwinner of the family, while a Kazakh man can be a homemaker and “god in the kitchen”. This won’t make Kazakh language and culture disappear.

It’s time to start viewing gender not as something innate, unbending, and inevitable, but as something acquired, variable, and preventable.

To understand the essence of the patriarchy, our roles and participation in it, and our moral responsibility to change it, we, as men, need to go through clean pain. This pain is the understanding that much of what you have said and done was wrong.

If men begin to understand their privileges and use them to support of vulnerable groups, find real strength in their vulnerabilities and self-compassion, allow themselves to experience and express the full range of human emotions, refuse to be hostages of far-fetched fears and political manipulations, listen to women, trust them, and learn from them, then they will undoubtedly improve their relationship with others, strengthen their mental and physical health, extend their lives, stand on the humane and just side of history, and find true freedom.

Yes, it will be painful, challenging, and confusing, but this is the path worth treading.

This is an abridged version of an article we originally published in Russian. It was translated into English by Dakota Crookston.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.