Julia Halušková was guilty of being married to a Ukrainian writer who fell victim to the Stalinist repression wave in 1937. He was executed, one among around a million political prisoners that were killed during the so-called Great Purge. She then spent five years in a prison camp in today’s Kazakhstan, not far from the capital Astana, along with her daughter and around 18,000 wives and children “of the traitors to the homeland”, the infamous ALZHIR camp.

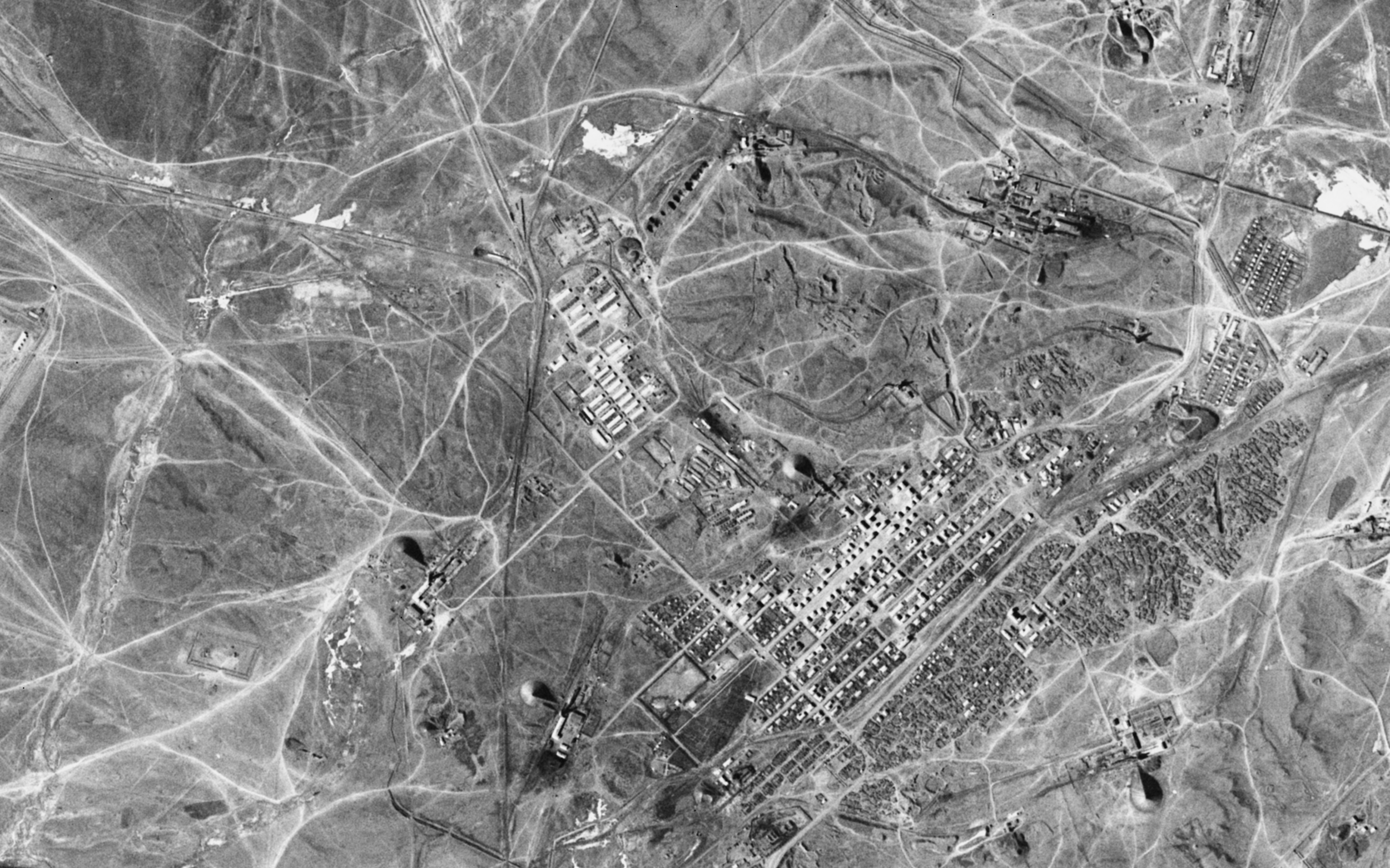

Within the massive Gulag system of prison camps, ALZHIR operated between 1937 and 1953. With the help of newly declassified CIA satellite imagery, a Czech crew traveled to Kazakhstan in 2021 to shoot a new documentary on ALZHIR and the massive nearby camps of KarLag and StepLag. The documentary, produced by Gulag.cz, premiered in Prague on March 5.

“I felt that there was something missing in these museums and that the history of these places was still pretty much unknown. When satellite images became available, I searched for Gulag sites and found many unknown ones,” Štěpán Černoušek, the head of the expedition in Kazakhstan told Vlast.

Černoušek had previously traveled across the former Soviet Union to find the places of repression and shine a light on the Gulag system.

The camps in Kazakhstan have been researched, documented, and filmed in the 70 years since their closure. But the end of the Cold War and the availability of increasingly more declassified documents has helped greatly in recent years to piece together the puzzle of such a systemic repression.

The Czech documentary “Step a Mráz” (Steppe and Frost) shows how the three camps (KarLag, StepLag, and ALZHIR) looked in the 1960s and 1970s as opposed to their current state of decay. Extreme weather conditions and lack of interest in preserving the buildings since their closure has turned them almost into ruins. Some of the buildings seen in the documentary were demolished shortly thereafter.

The documentary shows examples of Gulag architecture: Barracks built with the simplest materials and often poorly insulated, as well as more elaborate buildings which belonged to the camps’ administration. After the Gulag system was shut down, some of the buildings were, and some still are, used for different purposes, thus guaranteeing their partial preservation, although not always in their original form.

In an attempt to preserve the memory of Soviet repression in Kazakhstan, the expedition used 3D technology to produce digital renderings of the camps. These are now accessible on the web and could represent invaluable information for researchers of the Gulag system, especially in the face of ongoing demolition.

The Czech Inmates of the Gulags

The documentary follows the traces of Czech inmates in these three camps. New data, such as the one regarding Halušková, emerged through a collaboration with Memorial, an organization researching Soviet history that is now banned in Russia.

Details about the imprisonment of Halušková and her daughter are scant. She hailed from a Czech community outside the territory of today’s Czech Republic. She was married to Denis Haluškov, a Ukrainian writer, who was killed in 1937. Her husband’s alleged counterrevolutionary activities determined her fate. She was sent to the ALZHIR camp for five years and was only rehabilitated after Stalin’s death.

The stories of other ALZHIR inmates, Albína Zikmundová, Gabriela Zábranská-Ravva, and Evženie Věsniková, were better preserved. These women were all sent to the camps in the Kazakh SSR just because they were married to so-called “enemies of the people”, according to the Soviet secret police. The definitive history of the women and children who were detained in ALZHIR, however, has yet to be written. Most archival material is still under lock and key and until it becomes accessible it would be difficult to properly assess the scale of the repression and the atrocities. We only know a few names of the more than 18,000 women and children who went through the ALZHIR camp.

Preserving and Restoring Memory

The documentary was shot in the month of November, leading to several challenges due to extreme weather conditions. The battery-powered equipment would only work for a few minutes before powering off due to the extreme cold. The winter temperatures and landscape were ideal to convey a feeling of the conditions the inmates had to endure.

In Rudnik, a camp within StepLag, inmates had tried to protect their barracks from the harsh temperatures. They used soil to insulate their walls.

Černoušek and his crew received support from local universities and researchers during their expedition. Academic work on the memory of the Stalinist repression has continued in Kazakhstan, especially since independence in 1991.

Talking to Vlast, Černoušek highlighted the role of Turganbek Allaniyazov, professor at Zhezkazgan University, as well as other local museums and universities, in preserving both the historical memory and the physical sites.

“At one of the sites in Zhezkazgan, the ruins are being transformed into an open-air museum. When I was there the last time in 2016 everything was abandoned and there was a lot of trash. The preservation work is invaluable. There is even a fresco in Zhezkazgan’s former clubhouse, a rare case of Gulag artwork,” Černoušek said.

The archives could be crucial troves of documents that would bring to light both the inner workings of the system of repression and the personal stories of the inmates, who were sent to the Gulags from all over the former Soviet Union.

“It’s likely that the archives also contain more information on Czechoslovaks that ended up in the system. An easier access to the archives would make it easier to research the topic. The descendants of former guards in Dolinka with whom we spoke did not really have a grasp of the history of the place,” Černoušek said.

Luca Zucchetti is a contributing writer living in Prague.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.