- ВКонтакте

- РћРТвЂВВВВВВВВнокласснРСвЂВВВВВВВВРєРСвЂВВВВВВВВ

President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev announced that elections for the lower chamber of the parliament, as well as regional and local assemblies, will take place on March 19. And although there seems to be more space for opposition forces, this could be another ceremony that only benefits the president: The lack of meaningful structural reforms and the ongoing political repression, in fact, continues to hinder representation.

Tokayev was re-elected on November 20 for another term in office. According to the latest constitutional reforms, this would be a single seven-year term, after which he will have to hand over his post.

But if last time, like the previous ones, we again did not witness free and fair elections, why should we expect any change in the future?

Aisultan Seitov, a film director that recently debuted his first movie, Qash (Kazakh for “Run”), said in a podcast that “only one person needed these elections, and that person is Tokayev.”

There is truth in this statement, because Tokayev was the only one who benefited from this electoral campaign, which legitimized the referendum organized earlier in June.

Though always called before the term expires, snap elections surprised many, including the opposition movements. Activists were not prepared, as they are still barred from participating in politics: Just the basic requirement to have worked in government for at least five years excludes a priori a vast number of potential alternative candidates.

Independent observers and their organizations were also not ready. They were still grappling with recent threats to their existence, as NGOs came under fire from the government and its affiliated political commentators for their connections with the West and will now face harsher conditions to achieve accreditation.

Amendments to the law On Elections now require NGOs to apply for an official registration for every campaign they wish to observe, rendering the process more cumbersome and subject to arbitrary denial. This bill came into force on January 1.

Irina Mednikova, chair of the board of trustees at the Youth Information Service of Kazakhstan (MISK), a youth organization that is often involved in election observation, said observers could now face stricter restrictions.

“At the parliamentary elections in 2021, out of 230 of our observers, 120 could not enter the polling stations due to pressure and rejections on the spot. 15 people were not allowed inside due to problems with documents and a ‘lack of space’ at the polling stations. Seven human rights organizations faced unreasonable tax audits concerning foreign funding.”

With the new rules, Mednikova said the Central Election Committee could stall their requests and then just arbitrarily reject them.

Since former President Nursultan Nazarbayev resigned, and since Tokayev proclaimed a new course, under the moniker “New Kazakhstan”, the electoral and juridical infrastructure of the country have not changed. The promised reforms have not materialized.

Observing Elections

I have monitored the political situation since the snap presidential elections of June 2019, which Tokayev won by a landslide. He had served as interim president since March, when he secured Nazarbayev’s endorsement.

My sister and I observed the polling station at Asfendiyarov Medical University in Almaty. There, the self-proclaimed opposition candidate Amirzhan Kossanov garnered 1,052 votes, almost four times more than Tokayev’s 287. The voter turnout was comparatively low at 54%.

The network of independent observers proved not powerful enough to effectively poll voters across the whole country. For the first time after decades of shrugging elections off, in fact, in 2019 people were moved by a real drive to express their preference. Sure, there was a passive boycott and a rejection of the political circus, but these were the only weapons in the hands of a population whose human and civic rights are constantly under attack.

In 2019, Kossanov introduced himself as the alternative, although he quickly conceded defeat, too quickly for those who had believed in him. At the 2022 presidential elections, Tokayev had no real opposition or contenders.

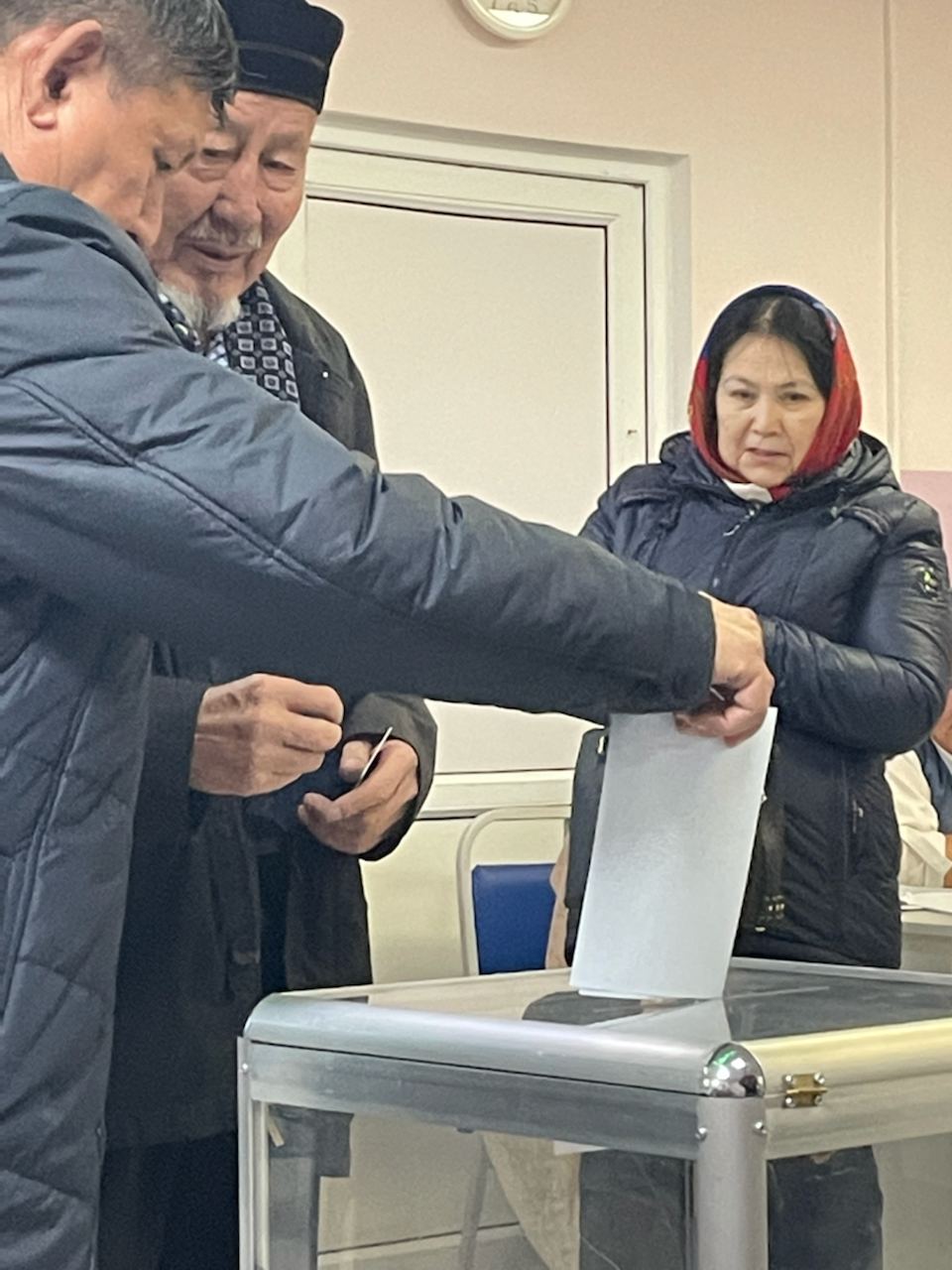

In November, I was stationed at the City Polyclinic n. 26 in Almaty. There, Tokayev won 509 out of 579 votes, with a meager 26% voter turnout. It is difficult to imagine that most of the people that I saw casting their vote would have still chosen Tokayev had they had an alternative. And who knows if they actually did vote for him, or if their ballots were tampered. Or whether they were pressured to vote. After complaints from commission members, some voters justified their practice of taking pictures of their ballots saying “it’s for a report to my boss at work.”

Observers from Below vs Observers from Above

If in 2019 I observed elections with MISK, in 2022 I decided to join another organization, Tauelsiz Baqylaushy (Kazakh for “Independent Observer”). I had met some of their activists during the rallies in the aftermath of Qandy Qantar (Kazakh for “Bloody January”, the violent repression of urban protests across the country). At the rallies, they demanded a transparent investigation into the killings and the torture that occurred in January 2022. I was also attracted by their grassroots spirit, given that they survive only through membership fees and donations by fellow citizens.

Their plan was to focus on one specific district in Almaty, in an effort to paint a representative picture even just of a small sample in the country’s largest city. In their report, Tauelsiz Baqylaushy said the voter turnout they observed was below 18%. On November 22, at a press conference organized by several NGOs, Tauelsiz Baqylaushy representatives said they would file 11 complaints to the court regarding the “gross violations of the electoral process” that they witnessed.

The Central Election Commission said that 28.7% of eligible voters came to the polls in Almaty. Whether we believe the official number or the more realistic 18% observed by Tauelsiz Baqylaushy, the turnout is too small for the results to be truly representative of the will of society. Naturally, elsewhere the turnout was shown to be much higher, with a countrywide total participation of 69.4%.

At the polling station I observed in November, there was pressure both from the authorities and from the authorities-backed “observers”. The observers’ seats were in fact packed with so-called observers who refused to name the NGO they were working for. There was an atmosphere of total distrust.

One of the ostensible observers yelled at me twice for moving around the polling station and for taking pictures. This person was more eager to prevent me from documenting violations than the electoral commission members, who are known to be the stricter ones. The government workers (among whom teachers, doctors, and nurses) selected for the commission were annoyed by my efforts in documenting the process, but I had clearly recited my rights, as the law allows observers to film.

The tension rose higher when I started filming the pretend-observer for yelling at me. He became furious and took a swing that hit the hand with which I was holding my phone. I filed a report on this incident and took the head of the commission to court for failing to protect the observation process. In the end, however, I lost the case. I was not backed by the other commission members or by any of the other so-called observers, who took his side. One of them denied the hitting, although there is video documentation.

My goal in taking the case to court was to clarify the rights of observers when documenting electoral violations. Do we have the full rights to record on camera? Can we freely observe without external or official interference? Can we move beyond the retractable barrier where they unlawfully confine us or should we sit quietly in a corner?

Mine was not the only case that was dismissed by the courts. Tauelsiz Baqylaushy had all of its 11 court filings struck out. Yet, we all saw violations documented by official and unofficial observers and posted to social media.

The most glaring example was perhaps a Facebook livestream by a Tauelsiz Baqylaushy observer, who was forced to leave the polling station when the count started. He then followed and filmed the commission chairwoman who had allegedly removed a large stack of ballots and was taking them to an unmarked car.

Such is the state of our electoral processes, made just to confirm one man’s power onto our country. This circus is only interesting to around 20% of Almaty denizens, most of whom were forced to go anyway.

In March, we are going to the polls again for another election. Based on my experience observing how these are held, I believe we will witness another attempt to falsificate the people’s will.

Suinbike Suleimenova is an art-activist, filmmaker, curator and author living in Almaty.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.