In November 2021, when I first met her, Katerina Suvorova, or Katya, was making waves. Her debut feature documentary Sea Tomorrow which she produced in 2016 was streaming on Netflix’s European platform. The documentary, about the ecological disaster in the Aral Sea, is the first film from Kazakhstan to stream on the platform. With her Netflix deal in the bag, the stage was set for Katya’s future prospects.

In late 2022, we met again at her new studio – a cozy spot in Almaty’s city center to talk about the present and future of Kazakhstan’s documentary film scene.

Documentaries are not typically the kind of blockbuster films that earn producers a lot of money, so how can they be made more popular in Kazakhstan and thus attract more local investment? Kazakhstan, after all, has its share of very wealthy, prominent entrepreneurs, who have the personal income to take the monetary risk.

In Kazakhstan, we have to work primarily with international money. It sounds sad because, I think, the process would go faster with local money.

I see that popular music and contemporary arts are evolving remarkably fast and are gaining support. And I know that film producers are moving to music because it's a more reactive sphere of work. Feedback and money can be turned around a lot quicker there.

Instead, cinema is only supported if commercially viable. Cinema must make money back. Every year, Kazakhstan is supplying huge amounts of money towards cinema. But I can’t say that the end result is something equivalent to music or contemporary art. The films coming out, they're not about art, are they? It's more of a business.

How can you then have state support without it being translated into mere propaganda?

In Kazakhstan, we are having our own Baby Boom. Our population is young. The youth are creative and want to explore. I see it! So as I'm going around the world with my projects I'm meeting many interesting people from different countries, especially from Eastern Europe. At a festival in Croatia, they were distributing documentaries for their local audiences as well as bringing in documentaries from abroad. This program cost them tons of money, but they insisted on doing it. Their government did not, or perhaps could not, stop them.

I encountered a similar practice when I was in Taiwan for another film festival. In Taiwan, producers and private investors were spending lots of money on these events. There, we discussed, promoted each other there. The government didn’t stop it. Didn’t regulate it. In this example, the government actually encouraged and sponsored it too. In Taiwan, it feels like it's all about shooting what you feel, and spreading it globally so people will understand that Taiwan is an individual culture, place, country, home. Hope.

These are festivals and programs where money and personal sacrifice are put on the line to see this section of the art industry grow.

I believe that our contemporary political structure in Kazakhstan simply doesn't understand this. The government set up the “State Center for Support of National Cinema” [colloquially called KazakhCinema, not to be confused with the state-owned studios KazakhFilm, ed.], but for now I'm not seeing anything artistic about the whole thing. They use art for their own purposes. Last year, there were changes to the rules for financing local films via KazakhCinema. Now something like 80% of films funded by the state need to reflect a positive view of the country. In one word, it’s propaganda. And the remaining 20% can be auteur, art films.

It goes like this: A talented newcomer goes to film school. Either here or abroad through family money. Then they come back home, make a name by doing commercials, and after that secure a decent budget – maybe government, maybe not – to make a first full-length feature. And that’s how one makes money in this industry. It's still individuals, individuals, individuals.

You're describing a Kazakhstani film industry that is individual-centric, but Hollywood-machine in nature.

Yes! I think that all people in charge of the structures funding cinema in Kazakhstan really dream about being Hollywood producers overseeing a Hollywood production. But Hollywood productions are totally different – they're separate from the government.

It’s actually not about “culture” when our Ministry of Culture’s money goes to ideas of making business out of the creative and cultural potentials of local artists. That money isn’t used to support culture or develop language, represent local attitudes, thoughts, pain…

How do local audiences factor into this?

Local audiences want to watch films and television shows that are of good quality. Who can blame them? But local audiences don't consume local films. The bigger budget things we have here cannot compete against Hollywood products, so it’s no surprise we are losing their interest.

Our audiences don’t want to watch the big budget local productions because of their low quality or because their messages aren’t appealing to critical cultural thinking. Forget trying to get them to watch our little movies that actually try to inspire viewers to ask questions, to debate our culture.

Instead, it is the government that must be proactive in how they promote culture and cultural discourse, rather than just being motivated by money, and imposing their own priorities as if it is a definition of culture. A good national reputation is not culture.

There seems to be a communication gap between the government and society.

These have been turbulent years for us. The transition from our first president to our current one. The arrests. The game of "is the regime changing or not?" It's absolutely unclear. So the government pours money into culture to make the current regime stronger. The agenda isn’t free, it’s dictated by decree.

So you and many others admit that at the end of the day you'd all prefer being funded by your own government?

Absolutely. Yes.

Do you see any way in which the government is changing its approach?

The rules changed in 2022 such that no newcomer filmmaker can apply for government funding with their own bank account. This new regulation just works in service of those who are already in. And of course they say that these new regulations came about in the name of anti-corruption. Sure, maybe.

I met with the government, together with other fellow filmmakers. We voiced our opinion. "These rules are bullshit. They deny opportunities for those looking to get into the industry in any meaningful way,” we said. And we aren't newcomers. We've all produced films, we have the experience to back up what we say.

Who was with you at the meeting with the minister of culture?

They were mostly producers, working with directors such as Farkhat Sharipov and Aisultan Seitov. And then there was me, representing myself as a producer.

I wouldn't say this sit down with the minister was a ‘big meeting’. I realized that the system hasn't been evaluated for years. Some bureaucrats weren't doing their job 10 years ago. Five years ago.

Things didn’t become more transparent, more efficient, and definitely did not become more accessible. And it's like an iceberg. We see only the tip of the mass of things that are wrong with the system. At the beginning of 2022, I had a lot of hopes for pitching to KazakhCinema. But now I realized that until the political system changes, nothing else will actually change. Unless we overhaul the system of sending money first from banks and ministries to cultural ministries and then to foundations, nothing will change.

Can you find room for optimism in these circumstances?

I know, this sounds terrible, sad, bleak… yet I believe it can be improved. It will not be easy, but I’m reminded of these dances originating from South America. Tango took off when several men were waiting in line at a brothel and, while they waited, they danced with each other. It was born out of circumstances, rather than deliberately orchestrated. Or like capoeira in Brazil where the national fighting art was banned by colonialists, so men started to practice it moving as if they were dancing.

To outsiders it may look like we're dancing, but really we're practicing our fighting so we don't forget what it is… Art under oppression can find a way to thrive. So if we talk about our film industry in a major sense, then I am sure in the long term it will find a way.

Without access to state money, how do you raise funds for your projects?

When I couldn’t get government money, I was going the independent route, applying to local, private Kazakhstani foundations. I didn’t manage to attract funds, so I moved on to international organizations. But they cannot give me the money to fully finance the project. It's against their policies. In short, I have to fund my own films piece by piece.

Traditionally, however, the Kazakhstani government retains all the rights from international co-productions. In the global film industry, this is crazy nonsense. It should work like this: One party brings 30%, another party brings 40%, and someone else brings the remainder.

Right now, we essentially cannot combine international and local money, otherwise the project will be stalled. The rules are unworkable. That’s why I'm forced to go straight to the international level, which offers support without any censorship or special requests.

But this way, because of foreign funding, the audience can say the topic was pushed from abroad.

Exactly! I'd be happier to produce with only Kazakhstani ownership. But we are not going to see the changes my fellow artists and I wish for within a year, or two or three. Should each of us put everything on the line for these changes? No. It’s just not something any one person can do, I think. If we want to change the system for the benefit of the creators, we have to be united too.

At the beginning of 2022, I started working with producer Yulia Kim, we were both angry at new industry rules. We shared both a common frustration and a commitment to making art. I try to always let other peers have a look at my new projects. When we get together, we have so many channels to communicate and seek support. I'm glad that I have this gang.

Besides individual support, do you feel there is also a lack of creative spaces?

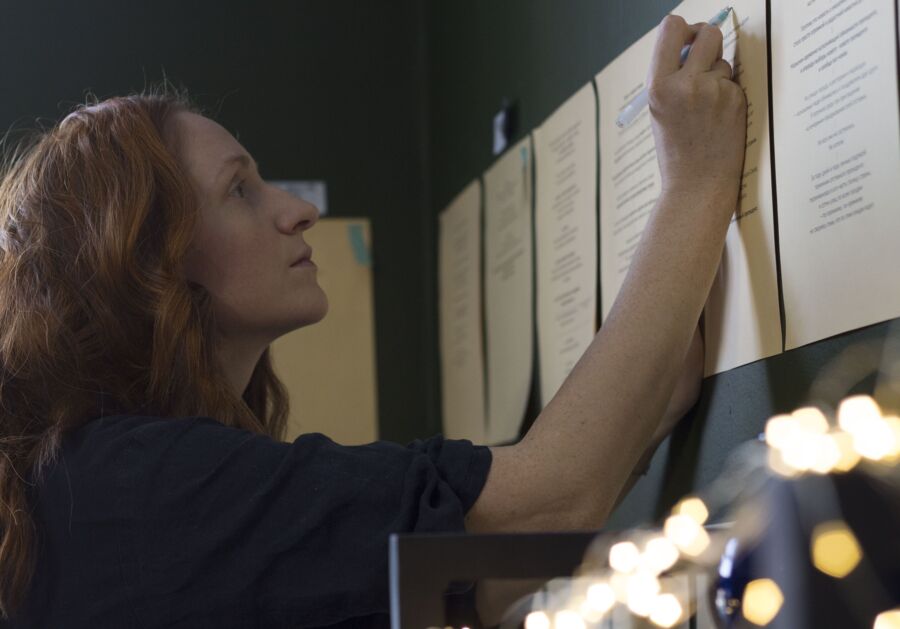

My work makes me feel abandoned sometimes. I'm cooped up here in my studio working on my films. It takes years to edit them. I worked on my current project for three years. Doing it by yourself in your own studio can be isolating.

You’ve established how you feel about interacting with KazakhCinema. But what about the biggest studio in the country KazakhFilm? Has your opinion of them changed?

I’m afraid of the bureaucratic vibes at KazakhFilm's studios, so I don’t even go there. I would prefer being in some studio, having other filmmakers around. I'm now working in an office building where my neighbor sells smartphones and my other neighbor is a concrete supplier. It's not a cultural space.

I also feel a vibe of competition among some of my colleagues. I just personally don't want this to be a rat race, I’d rather we came together.

Can the younger population be the catalyst of society coming together?

It looks like we are used to thinking that it's all about being led by strong hands, right? That's probably from where the common sayings like, broadly speaking, "Russia needs a strong President. Strong hands lead it." We imitate many things from Russia because of our Soviet past. We think we need a strong leader who would decide for us because we can’t communicate with each other. But I don't believe in that.

I noticed that young people in this country, especially those who are educated and have developed a global mindset, realize that there isn't only one version of life. They don’t accept that societal relations should be as vertical as the relationship between our government and its citizens has become.

We are moving from a highly regulated space to a place where people can communicate horizontally and form a community. But we're not there yet.

In the film industry, what I hope for is to see a circle of authors who are asking questions to each other about their work. The creation of a platform for discussion, not just to show off.

How can internationalization benefit Kazakhstan’s cinema and the global discussion about some of the most important topics in the country?

Whenever I go abroad to festivals I get that comment, "Oh my god, it's been so long since we've watched a documentary from Kazakhstan. We're glad to see you guys here! Let's talk." Sometimes I'm invited to give lectures. People abroad are interested in seeing what is happening here. We can do it by holding a mirror to ourselves and sharing its reflection. We can try to uncover a mystery, to fill in the blanks. We are bombarded with commercial products that showcase Kazakhstan as a place of horses, green steppes, blue skies, qymyz, and all that. But come on, what's actually going on here?

When I presented Sea Tomorrow in Taiwan, there was a huge discussion amongst the audience, because they have their own problems with ocean levels. They found something in common that sparked a discussion. We talked for an hour. In Paris, we were screening it on a Saturday and the hall was full. Tickets were sold out. And after the screening, the audience remained seated and wanted to talk about the people living near the Aral sea. Parisians!

These people have read about us, and have formed their own thoughts. They would challenge my view with theirs. It was amazing.

Let's work for ourselves, but also let's be in dialogue with the world.

Katerina Suvorova earned accolades with her debut documentary Sea Tomorrow (2016). In her current project, she is chronicling Kazakhstan's ever-changing civil society. The film will debut in the next few months. Her next scheduled project, Qyzbolsyn, is a feminist piece documenting the lives of women named Ulbolsyn (Kazakh for “Let it be a boy").

Eric Song is a writer and researcher interested in critical analysis of popular culture and entertainment in Kazakhstan and Central Asia. Originally from the US, he lives in Almaty.

Correction: The article was amended to reflect the state support for the Taiwanese film festival mentioned herein and to accurately describe Suvorova's upcoming project in her blurb.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.