A criminal court in Astana concluded Kazakhstan’s most groundbreaking trial on May 13, when the judge sentenced former minister of economy Kuandyk Bishimbayev to 24 years in prison for the murder of his wife, Saltanat Nukenova. The trial spanned for weeks and attracted widespread attention, with millions of viewers tuning in to watch the court’s live-streaming from across the post-Soviet region and beyond. This incident has sparked country-wide conversations about the state of domestic violence in Kazakhstan and the effectiveness of law enforcement institutions meant to protect women.

Despite public outcry, the government had resisted making decisive changes to the legislative framework regulating domestic violence. Finally, in mid-April, during the Bishimbayev trial, the government decreed that domestic violence should once again be regulated through the Criminal Code. [Note: In 2008, the government had moved domestic violence to the Civil Code] As the country watched the first live-streamed court proceedings in Nukenova's case, a groundswell of support emerged, with online flashmob actions under the hashtag #zaSaltanat and rallies both in Kazakhstan and abroad held by Kazakhstanis living in Europe and the United States.

The sweeping legal amendments adopted on April 15 expanded the definition of domestic violence and significantly increased punishments for offenders. The new laws impose harsher prison sentences for crimes ranging from intentional bodily harm to torture, rape, and even driving victims to suicide. In cases involving minors, the possibility of reconciliation between parties is now excluded, and life imprisonment will be imposed for violent sexual acts, murder, and sexual harassment of persons under 16.

One of the loudest voices calling for the legislative reform was Dina Tansari, the founder of NeMolchi.kz (Don’t Be Silent) civic organization. She has faced increased pressure for her activism following Nukenova’s death, with the prosecutor lodging six criminal charges against her related to an alleged fraud and embezzlement case. Widely known in the country, her organization helps bring spotlight to cases of rape and violence mishandled by police. In frequent posts that gain hundreds of thousands of likes and collect millions of tenge in donations, Tansari criticizes the ministry of internal affairs, specifically the police’s inadequate handling of sexualized violence cases. Due to the latest prosecution in November, Tansari’s accounts were frozen, she was declared wanted, and placed on the international wanted list. The government’s actions towards Tansari seem out of touch with public demands and even strategic goals Kazakhstan has set forward.

Having Experienced multiple waves of geopolitical and economic instability in recent years, resource-rich Kazakhstan has aimed for decades to become one of the most developed nations in the world. Alongside economic and institutional factors, the government needs to pay close attention to policies and issues that specifically impact women.

Official statistics reveal a growing trend in the male population, with a particular surplus of males under 27 years old. The proportion of women, though still slightly higher than that of men among older people, has been gradually decreasing year by year. Over the past five years, the average annual growth rate for women was 1.2%, lower than the 1.4% increase observed for men. The number of young women aged 14 to 28 dropped by 0.1%, totaling 1.83 million, while the number of young men in the same age group increased by 0.1%, reaching 1.92 million. The family institution is also weakening, with Kazakhstan ranking 16th in the world for divorce rate, possibly reflecting the casual attitude towards domestic violence. The problem of gender imbalance is not unique to Kazakhstan – other countries in Asia, notably China and India, face similar challenges. Some argue that this imbalance might have implications related to increased violence, crime, and even armed conflict.

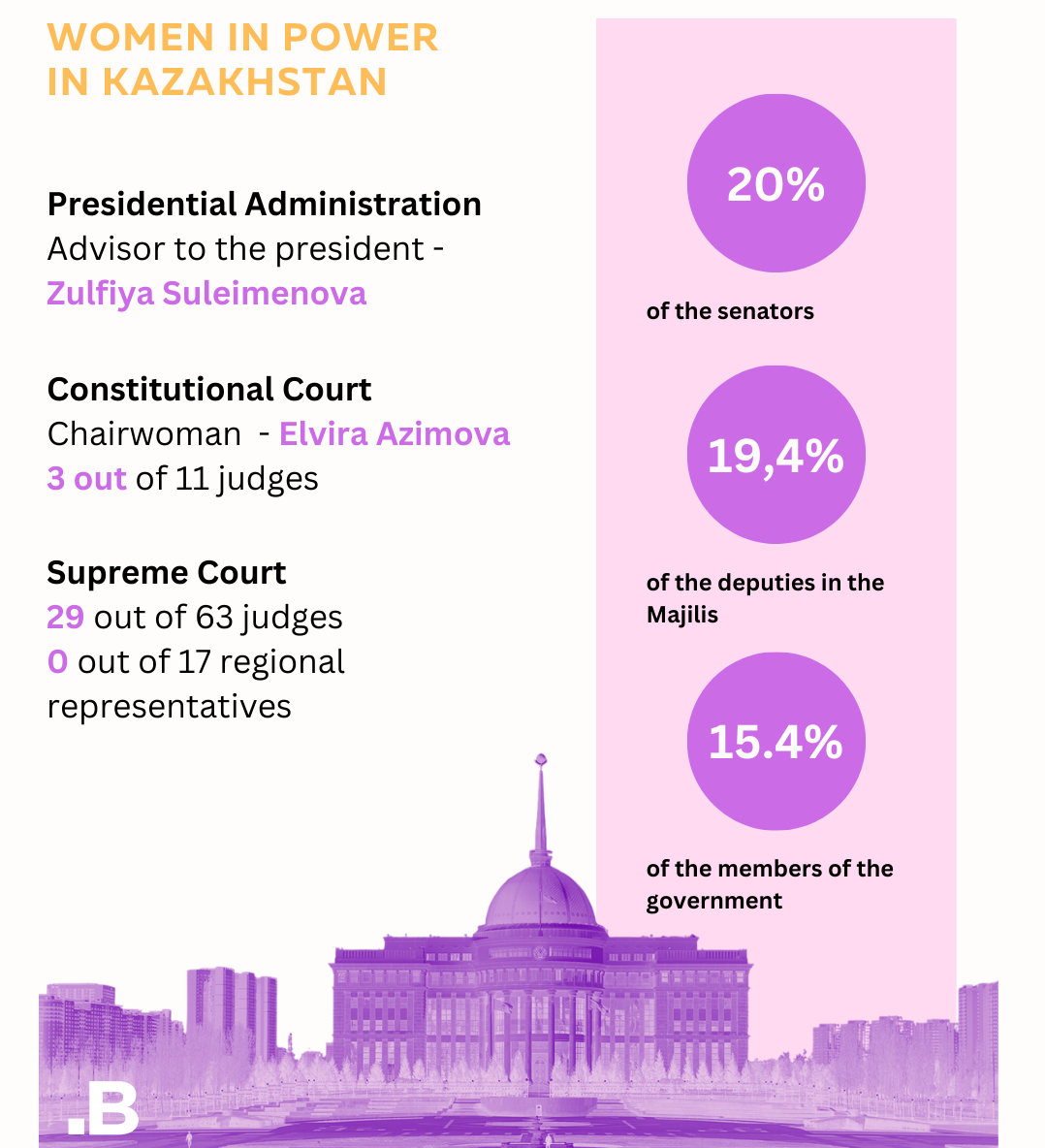

Along with the rise in male population, Kazakhstan faces another potential demographic challenge that could impede the government's aspirations. Despite women performing similarly or better than men in many metrics, these accomplishments are not translating into tangible benefits, including high-ranking posts. The official numbers provided by the Kazakhstan’s Statistics Committee are indicative of this paradox. While women outnumber men in higher education degrees at all levels, constitute the majority in science, and lead research and development programs, they are missing in the major decision-making positions. In 2022, for example, women occupied only 21% of leadership positions in higher educational institutions, with men holding the remaining 79%. This pattern is mirrored in other decision-making structures across industries, including the highest positions within the government, where only four women are part of the cabinet, or the meager 20% presence of women in both the Senate and the lower house of parliament.

If Kazakhstan fails to address the need for safety and create equal opportunities for career advancement, it risks exacerbating the issue of brain drain among women. This is particularly true for highly educated women, who face systemic barriers despite their qualifications and earning potential and might opt out to seek opportunities abroad. This situation is further worsened by institutional failures to protect women from violence, adding another layer of complexity to their challenges.

In this context, the new amendments to the law on domestic violence in a country hungry for government action are welcome. However, some question the effectiveness of their implementation, particularly in remote villages where patriarchal norms remain deeply entrenched. Support centers for victims of violence are already overwhelmed, receiving more calls than they can handle each day. The ministry of internal affairs has also raised concerns about the practicality of the new laws, arguing that authorities may struggle to keep all abusers under arrest. Their calculations suggest that around 5,000 people could end up in pre-trial detention centers following the adoption of these amendments.

Nukenova’s case has brought momentum to the overlooked crisis of domestic violence and women’s rights in Kazakhstan. While the new legal amendments are a step in the right direction, true progress will require a fundamental shift in societal attitudes and a commitment to justice that extends beyond the letter of the law. As Bishimbayev’s trial was wrapping up, another case of domestic violence involving a high level official has emerged. Karina Mamash, the spouse of an advisor to Kazakhstan’s Ambassador to the United Arab Emirates, accused her husband of perpetrating violence against her for nearly 10 years. It is yet to be seen if the government will be able to carry forward the progress shown in Bishimbayev’s case.

Raushan Zhandayeva is a PhD candidate at George Washington University studying Eurasian politics, with a specific focus on Central Asia. Aliya Askar is an independent researcher based in Kazakhstan.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.