Осы мақаланың қазақша нұсқасын оқыңыз.

Читайте этот материал на русском.

The overwhelming approval for the construction of a nuclear power plant in Kazakhstan shown at the October 6 referendum was, to say the least, doubtful, according to experts and observers, who pointed to gross violations during the polls as well as to waning political participation.

A string of unfulfilled promises since Qandy Qantar (Kazakh for ‘Bloody January’, the violent repression of urban protests in 2022) disappointed Kazakhstanis, who showed little interest in the referendum, which President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev pushed for already in 2023.

Ever since taking power in 2019, Tokayev had also announced a number of reforms, but the changes only further stifled opposition and political participation. Тhe trend continued during the referendum, as police arrested and filed criminal cases against dozens of activists.

While the authorities said the referendum would represent an example of direct democracy, political scientist Dosym Satpayev and sociologist Serik Beissembayev told Vlast that this was an instrument to rubber stamp a decision that had been already made. A track record of increasingly intense repression against the opposition, both experts argued, was inevitable, given a growing dissatisfaction across society towards the institutions.

For about a year, the central and regional governments have scrambled to put together public hearings and expert discussions, to which they only invited specialists loyal to the government. Government agencies repeatedly said they had nothing to do with the hearings, attributing them to the goodwill of civic activists. In fact, these events were organized by groups such as the pro-government Civil Alliance.

The main refrain at each of these events was the issue of energy security: The country’s increasing electricity consumption would put it at risk unless a nuclear power plant was built. Neither the authorities nor the government-friendly groups offered any alternative options to make up for the increased electricity demand. The “yes” side of the referendum also routinely ignored and marginalized the experts who came out against the nuclear project.

A few days before the referendum, police detained about 40 activists across the country. They had voiced their criticism towards the planned nuclear power plant. Some of them now face criminal charges, while a handful were given a two-months detention sentence for allegedly “organizing mass unrest.”

Lawyer Galym Nurpeissov told Vlast the latter case was classified and the lawyers were required to sign a non-disclosure agreement regarding the case materials.

The Results

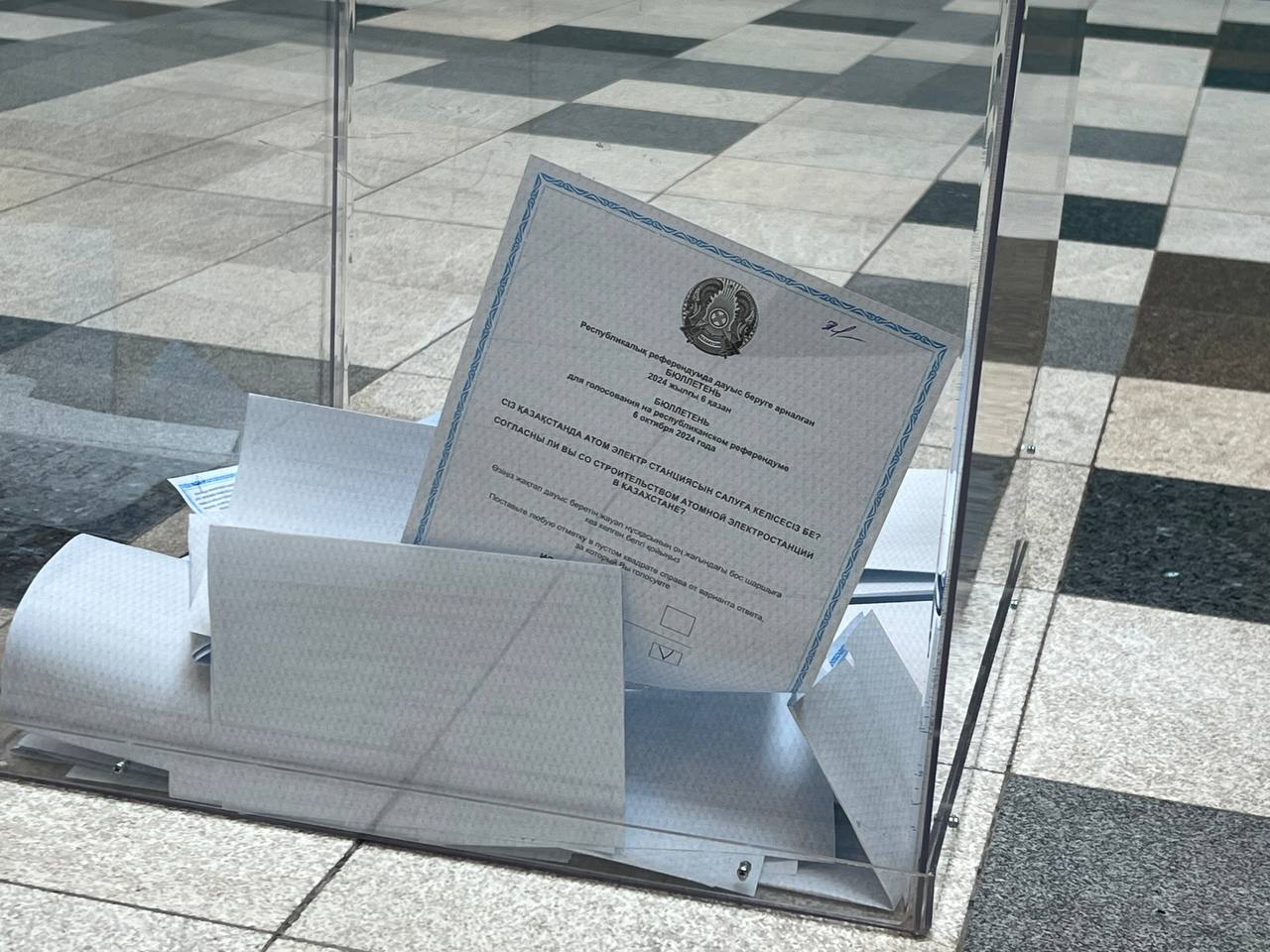

More than 5.5 million people (71.12% of the total) voted in support of the construction of the nuclear power plant at the referendum, according to official data. Independent observers, however, said the numbers for both the turnout and the voting results are unreliable.

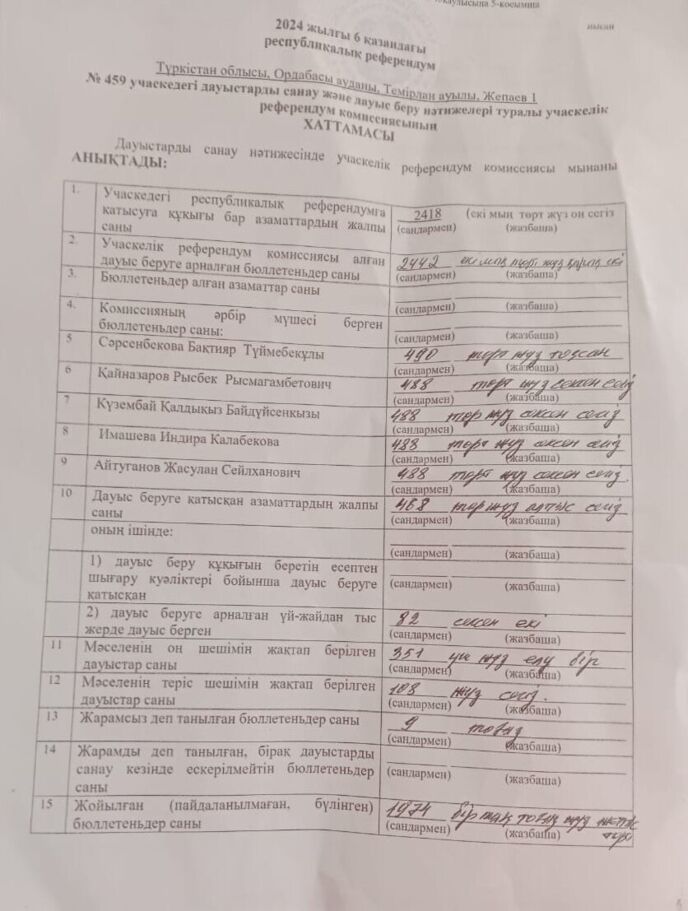

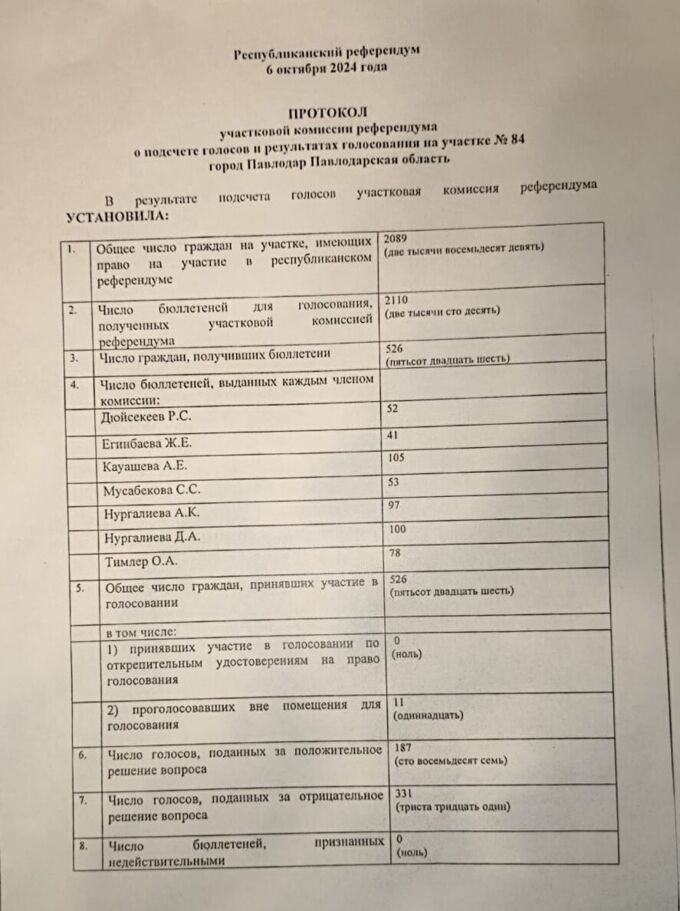

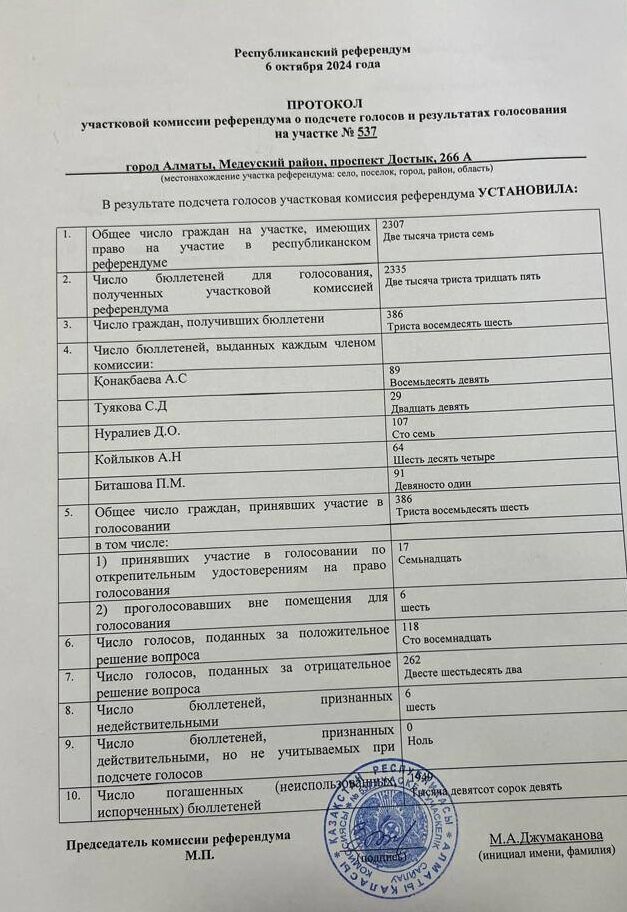

Vlast collected voting protocols from independent observers and open sources, showing that the “no” vote stood at 57% at 31 polling stations in Almaty, Uralsk, Astana, Pavlodar, Semey, Shymkent, and the Turkestan region.

In Almaty, while the official statistics give a 54:46 “yes” victory, the evidence we found says that 55% of the voters were against.

Observers also recorded a number of gross procedural violations. Berik Abenov, from the Uly Kosh Foundation, filmed a woman in the village of Temirlan in the Turkestan region throwing a stack of ballots into a ballot box and then running away.

Kural Seytkhanuly, also from Uly Kosh, noticed a person in Turkestan trying to stuff a handful of ballots into a ballot box. He reported this to the commission chairwoman, who refused to take action. The prosecutor's office also left this case unchecked.

Some observers, including Seytkhanuly, were removed from the polling stations.

“My only fault is that I did not remain silent after seeing violations. If I remain silent, what kind of observer am I?,” Seytkhanuly wrote on his Facebook page.

Another case involved journalists Lukpan Akhmedyarov and Raul Uporov, who were listed as observers in Astana for the Erkindik Kanaty Foundation. Other observers, however, asked the commission to remove them.

“There were no grounds for Lukpan and Raul to be removed. These decisions were made arbitrarily and illegally. Observers do not even have the right to petition for the removal of their colleagues,” an Erkindik Kanaty spokesperson told Vlast.

Inactive Activists

This past referendum, if anything, was a sign of a weakening public participation across the country.

Vadim Ni, an environmental law specialist and a co-founder of the platform AES Kerek Emes (Kazakh for ‘No Need for NPP’), said that only a limited circle of people was involved in their public discussions during their campaign for the “no” at the referendum.

"The lively Almaty activist community was only there to oversee the voting process. Unfortunately, there was no active participation earlier. Activists failed to coalesce," Ni told Vlast.

Roman Reimer, co-founder of Erkindik Kanaty, agreed: “Ahead of the referendum, there were only isolated attempts to register groups and create a coalition among those who oppose the construction of the nuclear power plant.”

According to Ni, there was simply too little time to organize a campaign. On September 2, during his speech to the nation, Tokayev set the date to October 6, just five weeks later. This was not enough for a detailed discussion on such a complex topic, Ni quipped.

Trust Me, I’m Listening

Political scientist Dosym Satpayev told Vlast that the recent referendum has nothing to do with direct democracy, as touted by the government. He argued that referendums are a tool often used in authoritarian regimes to create the illusion of democracy. In Kazakhstan, this strategy already had various names since Tokayev came to power: from “New Kazakhstan” to "Listening State".

"This referendum was the fourth in the history of Kazakhstan and the second after Qandy Qantar. All of them were a tool for manipulating public opinion in order to legitimize a decision that had already been made. Ahead of the vote, there was always strict control and pressure on opponents," Satpayev said.

Sociologist Serik Beissembayev said that a 63.6% turnout was unrealistic. Turnout had shown a constant decline in previous electoral rounds.

"It wasn’t a nail biter. Government officials at all levels echoed the president's mandate, calling for a ‘yes’ vote. The people understood that the country's leadership had already made a decision. Citizens who expressed the opposite point of view were stigmatized," the Beissembayev noted.

Tokayev’s unfulfilled promises after Qandy Qantar were the reason for society’s apathy and disappointment, which should have translated into a lower turnout.

"What was under [former President Nursultan] Nazarbayev has quietly merged into the current reality. Referendums and elections in our authoritarian system have remained a tool of political technology, not public policy. Therefore, we see harsh pressure on any anti-government activist," Satpayev added.

Beissembayev and the Demoscope, a research organization, planned to conduct a telephone survey that could provide alternative data on turnout and the level of support for the construction of the nuclear power plant. However, the Central Election Commission refused to accredit them.

"This amounts to censorship. This is the government ordering to hinder the work of an independent research organization. I think that the entire system is set up to control the media space and suppress independent sources of information," Beissembayev told Vlast.

The government fears society, Satpayev argued.

"The elites are currently discussing whether Tokayev will extend his term of office by changing the Constitution or find a successor. The construction of the nuclear power plant will overlap with the next transition period, and those who will build it need a stable regime,” Satpayev said.

Against the backdrop of the transition, Satpayev expects more repression. According to him, the authorities will do everything in their power to silence discontent, because they see them as a source of instability.

Beissembayev also expects a strengthening of the current authoritarianism.

"There is a growing distrust towards the entire political system of Kazakhstan. We have returned to the same system that was under Nazarbayev. And this could be the fuel of future protests. When people do not trust the political system, they are more prone to radicalization," Beissembayev said.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.