Читайте этот материал на русском.

On Sunday, October 6, Kazakhstan will hold a referendum on the construction of its first nuclear power plant. Based on the messages coming from local state-owned and private media, one would only hear arguments coming from local state-owned and private media, they would only know the arguments in support of atomic energy. Even bloggers and influencers have flooded the Internet with posts and viral videos campaigning for a “yes” vote.

Vlast analyzed how the state propaganda in favor of the nuclear power plant is set up and the rationale behind such a campaign.

State Broadcast

Kazakhstanskaya Pravda, the state-owned newspaper, provides the clearest example of government propaganda.

In a reportage from an August 20 public discussion in Astana, the KazPravda authors completely disregarded the opinions of the opponents to the construction of a nuclear power plant (NPP). Eyewitnesses reported that critics were not allowed into the hall, and the microphones of those speaking against the NPP were turned off. If one only looked at the article, they would think that "an open microphone was available to all in attendance."

The article also fails to mention that opposing voices were barred from participating as speakers in these public discussions. Instead, the piece referenced their interventions in a derogatory way, labeling them as “advocates of the saxaul” and “people afraid of devilish [shaitan] machines” – essentially denigrating their scientific knowledge and dismissing them as gullible conspiracy theorists.

Speakers in support of the construction of the NPP were treated differently, with their arguments carefully spelled out.

“Today there is no alternative to it [nuclear energy – ed.]” said the author of the piece toward the bottom. “Wind energy is not enough to cover the electricity deficit in Kazakhstan,” was the main refrain.

"It's the 21st century. Gone are the days when people were afraid of shaitan machines, when Indians were afraid of conquistador ships," the author writes.

The cover photo for this article shows a poster “SAY YES TO NPP” held by students.

This is just one of many pieces on the KazPravda website. On September 24 alone, the newspaper published nine articles about the NPP. From August to September, more than 100 pieces were published, four times more than in the previous seven months.

Other state-owned outlets such as Kazinform, Egemen Kazakhstan, and Elorda.info published between 63 and 100 stories in the two months prior to the referendum, a dramatic increase compared to their previous coverage.

“No need to be afraid of peaceful atoms”, “Nuclear power plants are our development, our future!”, “Wonders of the Universe: A nuclear power plant will be built on the Moon ”, and “The Sun is also a nuclear reactor” are just some of the headlines that these newspapers featured.

Once President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev endorsed this plan, the path towards this kind of coverage was paved, argued political analyst Dosym Satpayev.

“The government is working according to old patterns. The entire government apparatus has received a clear signal to direct all its resources to promoting the construction of the NPP,” Satpayev told Vlast.

Assem Zhapisheva, who founded and edits the independent media outlet “Til kespek zhok”, said that these pieces contain the standard characteristics of propaganda.

"The propaganda around the NPP project hides, distorts, and manipulates facts. We are not presented with the risks of environmental damage, especially concerning Lake Balkhash, or with alternative contractors other than [the Russian state company] Rosatom. We are not allowed to learn about alternative points of view," Zhapisheva said in an interview.

A Looming Energy Deficit

Propaganda articles are aimed at convincing readers of the need to build a NPP, mostly using the argument that since without it the country will experience an “energy deficit.”

An Egemen Kazakhstan piece starts off with the warning: “If a nuclear power plant is not built, we may face difficulties in ensuring the country’s energy security.”

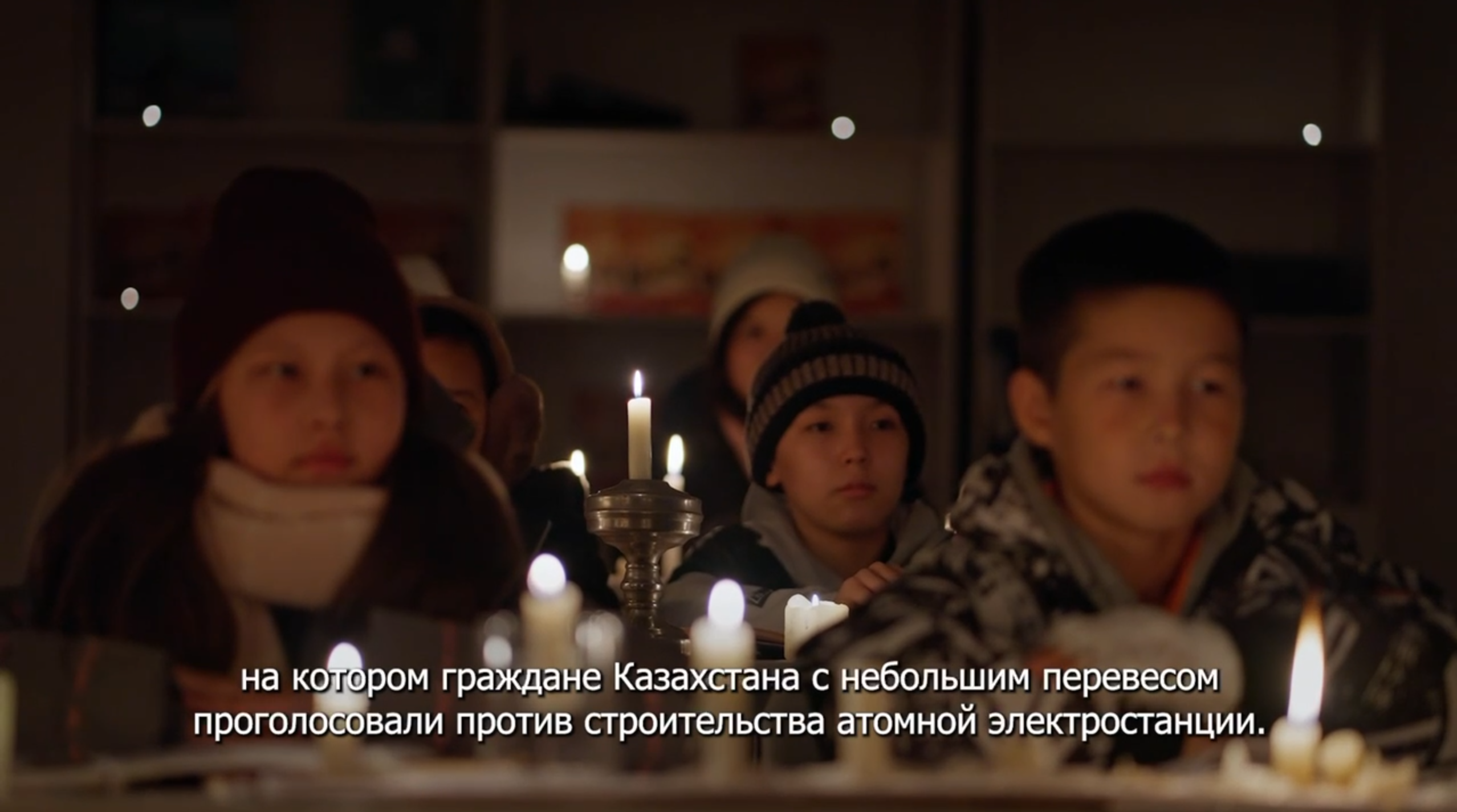

Professional video clips depicting a “future crisis for Kazakhstan” have begun to spread on social networks.

In one of them, children sit in a classroom in the winter by candlelight, and one student pedals a bicycle to turn on a heater. A history teacher tells them that during the 2024 referendum, citizens of Kazakhstan voted against the construction of a nuclear power plant “by a small margin.”

"The energy crisis, which had been brewing for a long time, reached its peak by 2030 and threw Kazakhstan back several years," the teacher says. The video ends with an appeal to vote “yes” in the referendum.

Sociologist Serik Beisembayev told Vlast that all this clearly shows that “the government is conducting an organized campaign.”

“If all of them present the same theses and arguments, it’s clear that this is a coordinated effort from the center,” Beisembayev said.

According to Satpayev, however, the people are not easily swayed by such propaganda. He argues that distrust towards the government has now reached its peak.

Real Expertise

The experts quoted in state propaganda pieces are almost exclusively supporters of nuclear power.

"Our republic is now, figuratively speaking, on the edge. Either we get lost in the ‘fan darkness’ [a derogatory metaphor against wind energy – ed.], or we build a nuclear power plant and make a civilized transition to a new technological order," the chairman of the board of the chamber of energy auditors, managers and experts, Marat Yessekin, told KazPravda.

State media often quotes Vadim Titov, a Rosatom representative. Both Kazinform and KazPravda featured him, essentially lobbying for the “benefits” that his company could bring in building Kazakhstan’s first NPP.

Rosatom is one of the companies that Kazakhstan is considering as potential partners in the construction project. The government of Uzbekistan has already signed an agreement to begin construction of several low-capacity nuclear power plants with Rosatom.

"I think the NPP project is connected with geopolitical pressure.There is significant pressure from Russia to speed up the process," Satpayev told Vlast.

Other experts, often quoted by state media, have little to no connection to the energy industry. Kazinform often refers to Ravshan Nazarov, a senior research fellow at the Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan, whose philosophy degree makes him a questionable voice on the topic of nuclear energy.

The media also published the results of various social surveys, which show that the number of supporters is “steadily growing”: from 53.1% at the beginning of August to 72.9% just a week ahead of the referendum.

Beisembayev said these numbers are hardly reliable and urged caution:

These surveys were in fact conducted by state-affiliated organizations.

"I don't think they can independently conduct research and publish data without the top-level approval. Our independent organization submitted documents to the Central Election Commission together with MediaNet earlier this year, but we still haven't received a response," he said.

Dismissing, Discrediting, and Denigrating Opponents

The propaganda machine brands opponents of the NPP as manipulators, accusing them of lobbying for “foreign” interests.

KazPravda pointed to them – without mentioning anyone making these arguments – saying that “they use dishonest methods of comparing nuclear power plants with nuclear weapon testing grounds.”

Other pundits who have sided with the construction of the NPP and have been featured in the media include controversial talking head Marat Shibutov, who became famous in 2022 for his comments on Qandy Qantar (the violent repression of urban protests of January 2022) and political analyst Gaziz Abishev, whose media outlet Turan Times published fakes about independent candidates during the 2023 parliamentary elections.

Private media outlets, especially those that publish articles through a state tender program, also feature propaganda pieces.

Abishev’s comments, for example, were published in popular private outlets such as TengriNews, Orda, and Informburo.

Orda cites Abishev as saying that “the opposing side is highlighting the dangers of nuclear power plants rather on an emotional level, without substantive evidence.”

Orda was in the spotlight in September 2023 after publishing a smear piece against the opponents of the NPP. The piece, titled “Foreign trace: who is behind the opponents of the construction of a nuclear power plant in Kazakhstan,” claimed that the opponents part of an organized group associated with opposition politician Mukhtar Ablyazov, who was convicted in Kazakhstan for embezzlement from his time as the owner of BTA Bank.

"Thus, it can be confidently stated that the Kazakhstanis protesting against the nuclear power plant are being centrally directed and supported by opposition figures associated with Mukhtar Ablyazov. Whether Ablyazov himself is involved in this is another question. But the existence of a single organized group that is trying to set Kazakhstanis against nuclear energy is an objective fact," the article, in its original version, argued.

The piece named and shamed members of the unregistered party "Alga, Kazakhstan!", whose leader Marat Zhylanbayev had been jailed for allegedly "financing extremist activities." The piece failed to mention that human rights groups have criticized both the charges and the trial against Zhylanbayev as politically motivated.

Orda also reported on Ablyazov’s connections with energy specialist Asset Nauryzbayev, who is an outspoken opponent of the nuclear power plant project. In response, Nauryzbayev wrote that he “had not seen or communicated with Ablyazov either directly or through intermediaries for more than 20 years.”

Following criticism on social media, Orda first withdrew the article and then reprinted it, amending some of the most controversial parts.

Orda's editor-in-chief, Gulnara Bazhkenova, said that she did not have time to look over the piece before publication and that it was ultimately redacted for being too "one-sided."

"But the conclusions were correct: Many activists who are pushing against the NPP are members of Alga Kazakhstan. Just like the activists who went to speak out for the NPP are either sent by the government or by Amanat or members [of the ruling party],” she wrote.

Media outlets that are either owned or linked to the government also avoid reporting on the de-facto ban on holding rallies that the opponents of the NPP project face, or about the detention of activists, or about the press conferences held by the “NPP Kerek Emes!” (Kazakh for “No Need for NPP”) platform.

Satpayev believes that such a negative attitude towards the opposing side is fueled by “fear.”

“They are afraid: If the opponents of the NPP become more active, more public, and more numerous, then their entire project could be jeopardized if a large part of the population votes against it. This could lead to protests,” the political analyst told Vlast.

Beisembayev said that this is a “familiar pattern” of government behavior during all electoral processes.

"There is a chronic inability to establish dialogue, a lack of understanding that a referendum presupposes public discussion, and that it’s normal to have an opposing opinion. Instead, they immediately label you as part of the opposition, and law enforcement agencies react accordingly. Literally yesterday, those speaking out against the activists were detained," Beisembayev said, referring to the detention of 12 activists on September 30.

Anti-Mobilization

Another method of promoting the idea of building a NPP was the alleged “public support” of various civic groups, which gained traction across the media.

These groups include the pro-government Federation of Trade Unions, young scientists, workers at a cardboard factory, members of Atameken (the national chamber of entrepreneurs), various parties, and a group of “mothers of multiple children”.

“We have become convinced that nuclear energy is truly environmentally friendly,” Azamatkhan Amirtai, the chairman of the green party Baytak, told TengriNews.

The propaganda has also recently filled the social media pages of various organizations, especially through viral advertising. In a popular video, students from Taraz Regional University hold a flash mob, lining up to form the inscription “NPP” alongside the symbol of a heart.

Even famous singer Kairat Nurtas chimed in, calling for people to vote in favor: "The head of state said that Kazakhstan needs to build a nuclear power plant. Of course, we all support this."

Propaganda and Money

“The government is both stressing the importance of ‘listening to people’s opinions and weighing different points of view’ while at the same time paying for an aggressive propaganda in favor of the NPP, waging a powerful information war against its opponents,” Satpayev said.

Satpayev believes that Tokayev and his entourage fear social tension.

Beisembayev believes that propaganda is the government’s default tactic.

"At each poll, the institutional memory of the bureaucratic machine kicks in – propaganda has become a tradition before elections. Also, the propaganda machine involves a lot of money and keeps friendly media and bloggers in the loop,” Beisembayev said.

Satpayev added that such advertising budgets and campaigns are a cash cow for a portion of the political elite.

“Even under [former President Nursultan] Nazarbayev at certain junctures the government allocated a lot of money for advertising presidential elections, parties, and so on, but it was tempting to use this money for other purposes,” he said.

Zhapisheva is concerned that society is in the dark about just how much money is spent on such campaigns, “thanks to the efforts of [former minister of information and culture] Dauren Abayev,” who made government contracts in the information sector less accessible and transparent.

“But the fact that under Tokayev, spending on propaganda has increased several times over can be seen by how many people are employed both through traditional and social media,” Zhapisheva told Vlast.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.