Since the beginning of Russia’s war in Ukraine in February 2022, experts have repeatedly said that Russia’s influence in Central Asia could weaken and that China would try to strengthen economic cooperation. Yet, more than two years later, there has been no major restructuring of regional relations. On the contrary, the parties are expanding their interaction, covering the military field in addition to politics and economics. International relations scholars and analysts convened at CAPS Unlock to discuss recent trends.

According to Temur Umarov, research fellow at the Carnegie Berlin Center, a certain stereotype has developed in both expert and public discussions. The stereotype is that China and Russia dictate the dynamics of all political and economic processes in Central Asia and that the countries of the region passively follow their lead. For example, China allegedly influenced their vote at the UN General Assembly to serve its own interests.

Instead, Umarov argues that “Central Asian countries act out of their own pragmatic interests.”

“We underestimate the extent to which elites control the situation inside their own countries. Any action [influenced] by China or Russia is only possible if it fits with the local regime’s political agenda. That is, when Kyrgyzstan adopts the law on foreign agents, it does so because Kyrgyzstan, not Russia, needs it," Umarov said.

An important aspect in the policy of the countries of Central Asia is that they do not want to see conflicts between China and Russia. Therefore, they try to balance their positions by avoiding competition with each other. This includes the involvement of third parties in some issues. For example, Tajikistan, in addition to Russia, is asking India for help in ensuring security on the border with Afghanistan.

And this balancing act often allows Central Asian countries to turn any possible tension between Russia and China to their advantage.

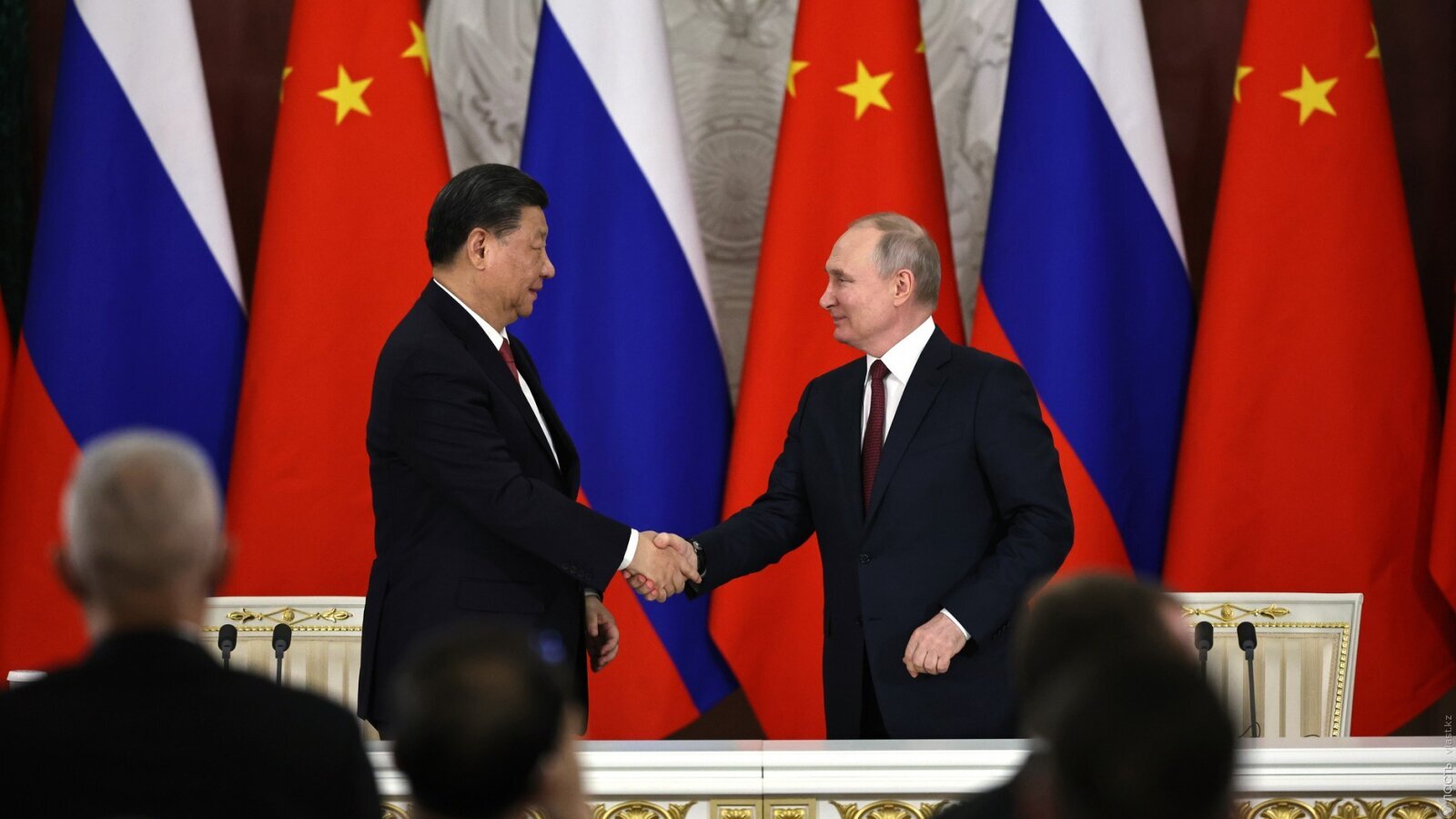

But now, it appears that lines of cooperation are emerging between Moscow and Beijing in the region, according to Umarov. And they do not just concern the economic side, for example, the uranium industry in Kazakhstan.

In particular, judging by the diplomatic documents they sign, Russia and China seem to coordinate their actions in Central Asia in an effort to prevent the spreading of so-called “color revolutions” into the region.

Emerging forms of military cooperation have also emerged, with delegations of Chinese military personnel visiting Russian bases in Tajikistan, or Russia and China hosting joint training exercises within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Russia and China also seem to want to avoid stepping on each other’s foot in Central Asia.

As an example, Umarov cited the “Gas Union” between Russia, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan, through which Russia purportedly wanted to increase its gas supplies to China. Yet, Russia is unlikely to be able to acquire the entire infrastructure network, because it is partly owned by China, through joint ventures with pipeline companies in Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan.

Moreover, the ambitions of both China and Russia are limited by how they are perceived by the Central Asian public. China is seen by many as an external threat, while Russia is seen as a country that has violated its own security commitments in the region with its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

This attitude towards Russia is confirmed by a study conducted by an assistant professor at Nazarbayev University Zhanibek Aryn. He conducted a series of focus groups to study how citizens of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Armenia perceive the activities of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO).

According to Aryn, although the organization is not limited to Russia’s participation alone, it is perceived as an institution of Russian foreign policy. And each side has complaints to one degree or another towards the CSTO.

Just a few years ago, the CSTO was not a matter of public discussion among residents of its member countries. Everything changed after the events of January 2022 in Kazakhstan, the border conflict between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, and the clash between Azerbaijan and Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh.

In Kazakhstan, some citizens claimed that Kazakhstan could have lost its sovereignty because of the intervention of CSTO troops during the turmoil of January 2022, after they were officially invited into the country to protect key infrastructure.

Kyrgyzstan’s government, for its part, was dissatisfied that Russia implicitly took Tajikistan's side during their border conflict in 2022.

Armenia was outraged that the CSTO did not defend the country when Azerbaijan shelled its territory and annexed Nagorno-Karabakh in 2023.

“The people of Kazakhstan said unequivocally that it is time to leave the CSTO, because it is not beneficial. In Armenia and Kyrgyzstan, opinions were divided. In Kyrgyzstan, there are two views: The CSTO is useless and inactive and so it makes sense to leave; or the opposite, that it would be unreasonable to withdraw. In Armenia, a lot of people believe it’s not necessary to leave," Aryn said.

According to Aryn, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia hold divided positions because they both face a threat from a third party, one from Tajikistan and one from Azerbaijan. Opponents of the CSTO in all three countries say that Turkey could replace Russia’s role.

Despite this, only Armenia has recently said it is willing to leave the CSTO, and many believe it was a form of bargaining. The country has threatened closer ties with the European Union if Russia does not change its attitude toward its security commitments.

Umarov believes that the balance of power between Russia and China in Central Asia is unlikely to change significantly in the next few years.

“As long as the current political regimes exist, coexistence [of all sides with each other] is possible. It seems to me that cooperation will only increase. But we don't know that for sure.”

According to Nargis Kassenova, senior research fellow at Harvard University’s Davis Center, major events such as a potential war in Taiwan represent key points of uncertainty.

Instead, Russia’s interest in Central Asia could be waning.

“If you read Russian experts, there is a big emphasis on working with the ‘global majority’, Africa, Latin America, and Arab countries. It is quite possible that Russia could shift their focus to those countries and pay less attention to the countries of the region,” Kassenova said.

According to Kassenova, Russia could increasingly push its influence through soft power in Central Asia. Following the example of its actions in the South Caucasus, this strategy may involve local NGOs, political movements, activists, journalists, and other channels.

“Although a lot of what Russia does is inefficient, in Central Asia it finds a fertile ground. On the other hand, for China it is difficult to work here,” Kassenova concluded.

This is a translation of an article we originally published in Russian. It was translated into English by Fatima Yerbolek.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.