- ВКонтакте

- РћРТвЂВВВВВВВВнокласснРСвЂВВВВВВВВРєРСвЂВВВВВВВВ

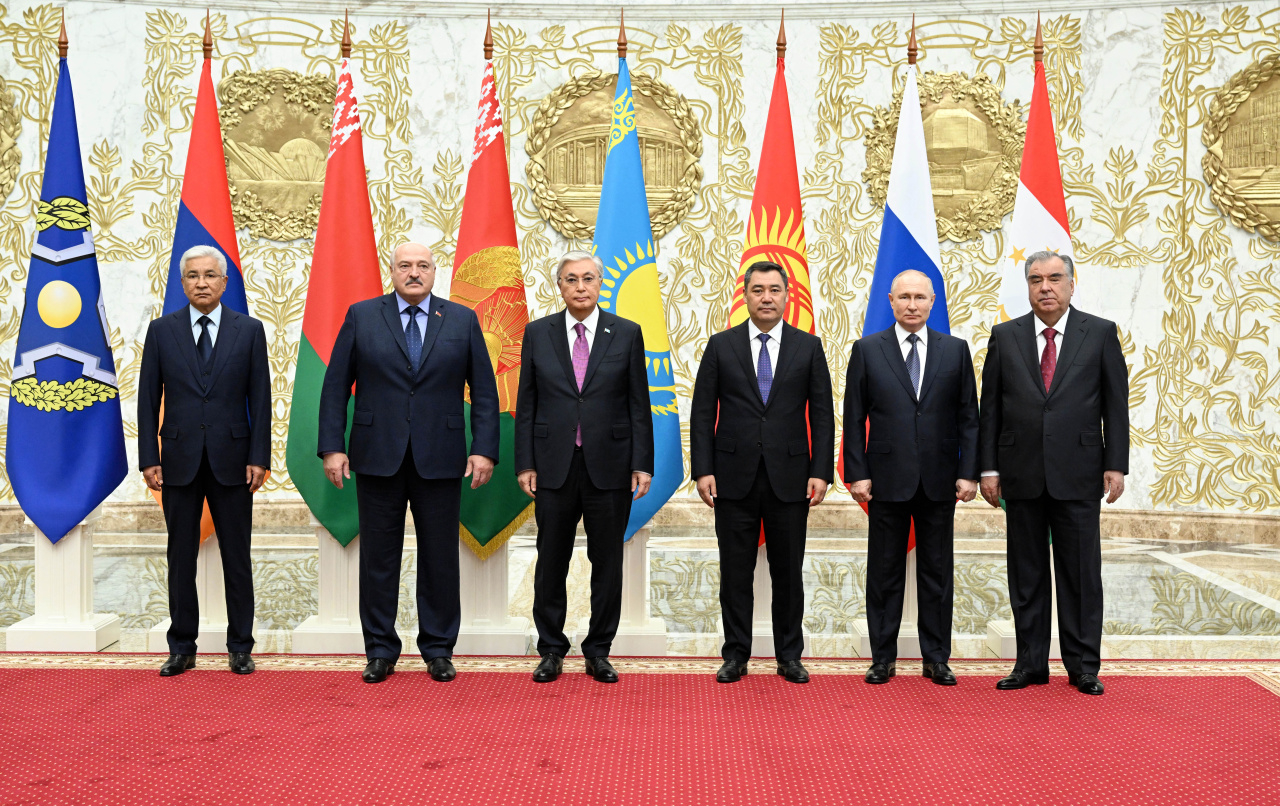

“Kazakhstan has no plans to leave this organization”. With these words, on November 23, deputy foreign minister Kairat Umarov wanted to dispel the rumors of a possible disgregation of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). On the same day, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev flew to Minsk for a meeting of CSTO heads of state.

Such rumors would not exist without the ongoing controversy over the weight and the role of the organization in the military security of its members.

Armenia, which had grown increasingly dissatisfied with CSTO’s cold reactions in the past, seems now to be gradually moving away from the alliance, something that became even more evident when Armenian prime minister Nikol Pashinyan missed consecutive meetings of both the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and the CSTO in the past two months, the latest of which in Belarus on Thursday.

When it was time to defend the territorial integrity of Armenia, in the framework of its heated conflict with Azerbaijan in September, in fact, Yerevan’s call for a CSTO military contingent fell on deaf ears.

Experts agree that the latest decisions from Armenia’s leadership represent a bump in the road that might affect the future of these Russia-led alliances.

Ups and Downs

A small contingent of troops had traveled to Kazakhstan in January 2022, after the CSTO agreed to send military help during Qandy Qantar (Kazakh for “Bloody January”, the violent repression of urban protests across the country).

In a message celebrating Kazakhstan’s Republic Day on October 25, the Russian embassy in Astana reiterated that it is willing to support and defend Kazakhstan’s sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity.

Last year, Pashinyan called the CSTO a crucial organization for regional security.

“Armenia, as a founding member of the CSTO, is committed to the further development of the Organization and considers it a key factor for stability and security in the Eurasian region, as well as for the security of the Republic of Armenia,” Pashinyan said, according to the CSTO website.

Armenia, however, is not treated with the same eagerness. On September 20, Azerbaijan launched a so-called "anti-terrorist operation" in the Nagorno-Karabakh region, which concluded with Armenia’s retreat and the incorporation of the contested territory into Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijan’s military offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh against Armenia failed to trigger an intervention from the CSTO, which many observers in the West call “Russia’s version of NATO”. This, in turn, has led to Armenia taking a distance from organizations such as the CIS and the CSTO.

Because of the CSTO’s inaction, Pashinyan called his country's security agreements with Russia "ineffective" on Sept 23.

Armenia refused to participate in a CSTO joint military exercise in Kyrgyzstan, ironically called “Indestructible Brotherhood” in October. Pashinyan also refused to attend a meeting of CIS heads of state in Bishkek, “due to a number of reasons” according to a readout of his telephone conversation with Kyrgyzstan’s President Sadyr Japarov.

The CIS and the CSTO comprise a different number of members. All CSTO member states, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Tajikistan are also part of the CIS, which also includes Azerbaijan, Moldova, and Uzbekistan.

Increasingly eager to apply to join the European Union, years ago Moldova started a process of withdrawal from CIS institutions.

Now, Armenia could be considering doing the same from both the CIS and the CSTO.

A Post-Soviet Transformation

The Armenian side, however, denies the existence of an exit plan.

“Armenia is not currently considering the possibility of leaving the Eurasian Economic Union or the CSTO,” Sargis Khandanyan, a member of Parliament and ally of Pashinyan, told Russian news agency TASS in October.

The transformations within the post-Soviet space pose a real threat to the existence of these organizations, Yauheni Preiherman, director at the Belarusian think tank Minsk Dialogue Council on International Relations, told Vlast in an interview.

“Both the CIS and CSTO are currently facing the most serious challenges since their inception, which is the result not of any specific conflicts or crises, but rather of the overall transformation of the post-Soviet space. We can now say that the post-Soviet space as such does not exist any longer,” Preiherman said.

Nathaniel Choi, whose research at the University of St. Andrews focuses on the CSTO, told Vlast that the role of these organizations is sometimes more symbolic than practical.

“The CIS serves as a domain for heads of state summits and overarching coordination. It is possible that Armenia’s cooperation within CIS structure will be reduced, given Pashinyan’s absence from the latest meetings. But this is unlikely to have a significant impact on Armenia’s alliance pattern,” Choi argued.

The CSTO, according to its charter, could not be involved in the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute.

“It is important to remember that Nagorno-Karabakh is not part of the CSTO zone of responsibility. The problem is that the CSTO did not intervene during the border incursion in Armenia proper last year, and that CSTO members refused to [condemn] Azerbaijan's incursions,” Choi said.

Despite these limitations, Choi contends that the CSTO still provides “organizational and bilateral perks” that Armenia is unlikely to find elsewhere. Preiherman agrees, making a direct link between these organizations and Armenia’s bilateral ties with Russia.

“I don't think that Armenia has many great alternatives security-wise, outside the CIS and CSTO. At least, not ones that can simply come as substitutes to Russia,” Preiherman said.

The Russia Factor

Russia contributes for 50% of the CSTO budget and pundits call it a “Russia-led” organization.

When the CSTO intervened in Kazakhstan in January 2022, more than 70% of its 2,500 soldiers contingent were Russian army men.

Thomas Baker, research analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit, told Vlast this approach was in line with the Kremlin’s goals to maintain regime stability in its neighborhood.

“The intervention in Kazakhstan during the violent protests showed that Russia is more concerned by disruptive regime changes rather than bilateral armed hostilities,” Baker said.

Yet, Kazakhstan has often rejected the label “Russia-led” for the CSTO. On November 15, a court in Shymkent imposed a fine on the local service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFERL) for “disseminating false information”. Sued by a local resident, RFERL had to pay 103,500 tenge (around $220) for having written that the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), a military alliance, was “led by Russia”.

Baker argued that the organization’s weakness has made it a bridgehead for Russia’s interest in parts of the former-Soviet space.

“The CSTO was not a strong military alliance to begin with. Its inability to intervene and resolve several conflicts over the past few years makes the organization appear more like a tool to promote and secure Russian interests in its so-called ‘near-abroad’,” Baker told Vlast.

After hearing about Pashinyan’s refusal to attend the Minsk CSTO meeting in November, Russia’s foreign ministry’s spokesperson Maria Zakharova said this is a Western plot against the organization.

“The West is obviously behind it. The West, whose plans in Ukraine have failed, is now gripping Armenia, trying to tear it away from Russia,” Reuters reported Zakharova as saying.

In September, when Armenia refused to host a CSTO joint military exercise, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said that decisions of this kind “require a very, very deep analysis”.

Armenia is also part of another organization, the Eurasian Economic Union, where Russia has a disproportionate weight. This is another organization that has come under criticism for its weakness in integrating its members’ economies.

At a forum in Moscow in May, Tokayev revived such criticism by saying that the close integration between Russia and Belarus, and the lack of progress in the integration of the economies of other members (Armenia, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan) represented an unresolved “conceptual issue”.

But Armenia’s lack of options makes it unlikely to cut ties with the CSTO, the CIS, or the Eurasian Economic Union overnight.

“Armenia is in a weak geopolitical position where it cannot trust Russia but also has not won the trust of the EU and the US fully yet,” Baker said.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.