A hydrocarbon exploration company in western Kazakhstan could be grossly underreporting methane volumes leaked in the atmosphere, experts argue, thus underplaying its damaging effects on the environment.

Buzachi Neft, the company exploring the Mangistau region for gas, said on August 7 that methane emissions are insignificant because it mostly is burned off in the fire that has engulfed the exploration well continuously since an accident on June 9.

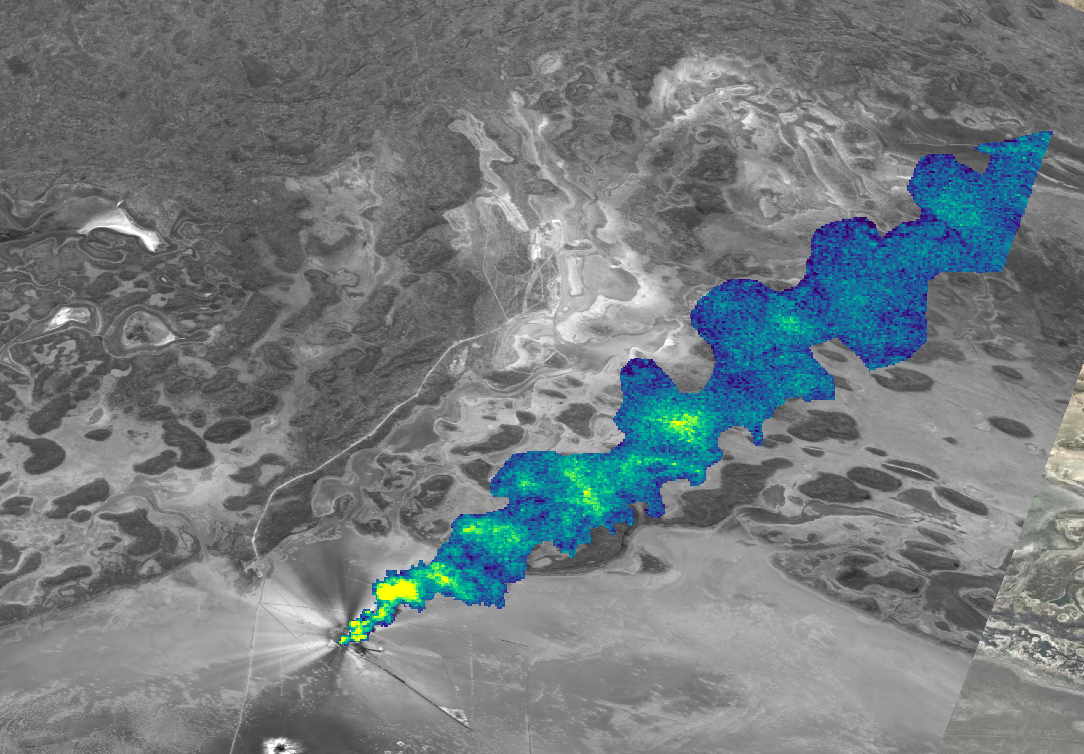

But Kayrros SAS, a French geoanalytical firm, said that it monitored the atmosphere with satellite imagery provided by several international agencies and found a massive methane leak, which it called “the largest emission from a single source this year, globally.”

The dispute over data, its analysis, the consequences for the environment, and the responsibility for the leak could misdirect the attention from methane, an invisible enemy that has a potent effect on greenhouse gas emissions globally.

Methane Pollution and Why It Is Bad

Methane is a highly-polluting gas that contributes greatly to global warming. Companies burn it to reduce the damage, because this process turns it into carbon dioxide, which has milder effects. When instead it leaks into the atmosphere unrestrained, methane’s contribution to global warming is 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Its dangerous nature for the environment is the reason that hydrocarbon companies flare methane that is extracted in association with crude oil and other gasses.

In the specific case of Buzachi Neft’s East Karaturun field, where well No. 303 has been burning since June 9, the company told Vlast that it has taken all measures envisioned in international standards to ensure minimal methane leaks.

“In order to avoid the unauthorized release of gasses in the area of well No. 303, the company regularly fires a burning charge into the clouds evaporating from the zone of active combustion,” Daniyar Duisembayev, deputy general director for strategic development at Buzachi Neft said in a written statement on August 8.

The cloud of smoke, according to the company, is a mixture of burned CO2 from the exploration drilling operations, which were conducted by Zaman Energo, a contractor of Buzachi Neft. The principal company, in fact, said they did not detect sizable volumes of methane.

“Not a single one of the burning charges that were shot sparked an ignition of the cloud above or around the emergency well, which is impossible were there a significant concentration of methane,” Duisembayev added.

The company said that these flares that were shot against the cloud would ignite a spark if methane were at levels above 5%. However, the company maintains that by their calculations and by the measurements done by the local department of the ministry of ecology, the concentration of methane is between 2% and 3%.

“Gross Underreporting”

Experts, however, point to a history of underreporting methane emissions, something that has been harder to conceal since the use of satellite imagery has allowed for a more precise, pin-point analysis.

Simon Pirani, honorary professor at the University of Durham, told Vlast in an interview that whenever there is a disagreement between independent monitoring and the company data, the public should trust the satellites.

“The companies have a history of underestimating the size of this problem. There's a big gap between the data they publish and the data from satellite monitoring. But we know that satellite data is tried and trusted. It's a very well developed technique,” Pirani said.

Antoine Benoit, a product manager at Kayrros SAS, said the company used two kinds of satellites and data from two different space agencies when they told the press that they had noticed a massive methane leak in the area.

“We detected the first emissions in early July with data from a satellite of the EU Space Agency, when the skies were clear and we could obtain unmistakable evidence. We were monitoring the area also because on June 9 we observed a massive smoke from that well, which we had detected from another test satellite, from the Italian Space Agency,” Benoit told Vlast in an interview.

The test satellite passed over the area four times on July 11, 17, 23 and on August 3, always detecting a methane leak. The lowest estimate recorded was 35 tons, while the largest was 107 tons per hour.

If we take the leak to be an average between the two extreme values, in these past two months this leak could be comparable to the worst anthropogenic methane leak in US history, recorded in 2016.

Another Two Months

Buzachi Neft, according to the latest financial data, is owned by businessman Murat Safin, who once figured among Forbes’ list of Kazakhstan’s richest. He owned upstream and downstream oil operations ultimately controlled by Timur Kulibayev, the son-in-law of former President Nursultan Nazarbayev. According to UK filings, Safin owns the company via AIL Alpha Corporation, registered in the Isle of Man.

Saule Assanova, the company’s director, said in a press release in July that Buzachi Neft plans to complete the extinguishing of the fire and the leak by October.

“Buzachi Neft LLP plans to complete all emergency work in October 2023.”

The date was later confirmed in a communication to Vlast. Deputy director Duisembayev added that “the main work on extinguishing the emergency well will begin on August 25. All measures to eliminate the consequences of the accident are coordinated with the ministry of energy and the local authorities in Mangistau.”

Assanova also passed the responsibility of the accident to the company’s contractor, drilling company Zaman Energo.

“According to a preliminary analysis, the accident [...] was caused by a violation of the technological regulations, which occurred due to [a] mistake or negligence of the drilling crew of Zaman Energo,” Assanova said.

To repeated requests for comment, the ministry of ecology did not answer.

It is unclear whether and how the company and the government would be able to extinguish the fire and the leak at the field, which are poised to become this year’s largest super-emitter.

Super-Emitting

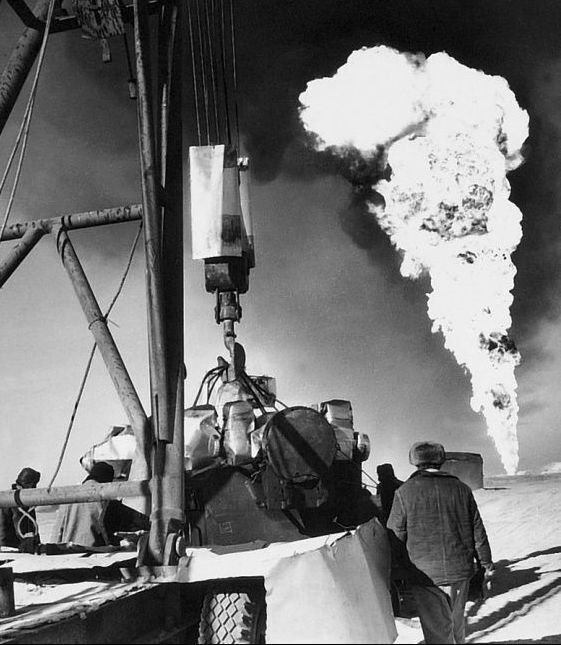

The flames at Karaturun bring back haunting memories in Kazakhstan, especially for what concerns the timing needed to extinguish the fire and to stop the leak.

In 1985, a fire at the Tengiz field, at the infamous Well No. 37, could not be extinguished for more than a year. Soviet engineers called up a team of international emergency workers to join forces to seal the gaping hole that was letting out gas and oil. In July 1986, 400 days after the original accident, the fire was extinguished.

The accident “significantly impacted biodiversity and public health within a 50–100 km radius,” the government later confirmed.

But accidents are not the only super-emitters, analysts say.

Pirani said that methane leaking from hydrocarbon infrastructure is not a new problem in the region.

“The high level of methane leaks from aging pipelines and hydrocarbon fields in Russia and Central Asia was a serious contributor to the greenhouse gas problem for many, many years,” Pirani said.

Antoine Halff, an energy industry veteran and one of Kayrros’ founders, told Vlast that oil and gas operations are generally leaky.

“New wells tend to emit quite a bit at the beginning. Plus, in countries like Turkmenistan and Nigeria, infrastructure and pipelines are in a state of disrepair, which turns them into super-emitters of methane,” Halff said in a conference call.

In order to avoid methane leaks, oil and gas operators should enhance their maintenance practices.

“The best way would be to capture the gas, which is not that expensive and would also be a win for the company,” Halff said.

An Easy Win

Halff also highlighted what in industry parlance has become known as “an easy win”.

“If we cut half of super-emitters, we could reduce global warming by 0.3 degrees Celsius in the first 50 years. It's impossible to reach climate objectives without addressing methane,” Halff said.

But oil and gas producers continue to rely on flaring, the burning of excess gas, or venting, the release of these gasses into the atmosphere.

For the environment, venting is the worst scenario. Methane is a far worse polluter than carbon dioxide, which is produced when methane is flared.

Flaring has thus become a common industry standard, said to eliminate at least 98% of the most dangerous gasses, such as methane. Or so the industry told the public.

“Flaring persists to this day because it is a relatively safe, though wasteful and polluting, method of disposing of the associated gas that comes from oil production,” the World Bank said on its website.

Last year, however, a group of US scientists also significantly downplayed the role of flaring in effectively burning off methane.

"Our findings indicate that flaring is responsible for five times more methane entering the atmosphere than we previously thought," Genevieve Plant, the lead author of the study at the University of Michigan told NPR.

In Kazakhstan and the neighboring region, Halff said the problem is in the approach to methane and its dangerous effects on the environment.

So far, at the East Karaturun field, the fire and the methane leak continue unabated according to video evidence and satellite observations.

“We received data just five days ago and the massive methane leak was still there, and we can see that it’s there, at the source of the accident,” Benoit said.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.