For every barrel of oil extracted in Kazakhstan’s oil-rich regions, some of the proceeds go to the companies selling the oil, while some go to the central government in the form of either taxes or contributions to the National Fund. Only a slight margin of the windfalls go to the local government, so while residents expect to reap the benefits of the oil bonanza of the past few decades, local infrastructure, as well as labor conditions are lagging behind.

Leaving aside a long, profound, and entrenched history of bribery and corruption, typical of the oil business, new data shows that transnational corporations (TNCs) in Kazakhstan have systematically undercut local workers by hiring them through contractors who severely underpaid them.

Осы мақаланың қазақша нұсқасын оқыңыз.

Читайте этот материал на русском.

Trickle Down

Galymbek Mussin is the ex-director of Asia Operating Corporation (AOC), a manpower subcontractor based in Atyrau, the so-called “oil capital” of Kazakhstan.

Oil permeates the city, which hosts the headquarters of the two largest oil producers in the country: Tengizchevroil (TCO) and the North Caspian Operating Consortium (NCOC), which extract oil at the Tengiz and Kashagan field respectively.

AOC provided workers to TCO through an intermediary: Senimdi Kurylys, a joint venture established in 2000 by US’s Bechtel and Turkey’s ENKA. Senimdi Kurylys manages thousands of workers and participates directly in TCO’s (as well as NCOC’s) tenders. In 2023, it also ranked 31st in the list of top tax contributors to Kazakhstan’s budget.

TCO awarded Senimdi Kurylys contracts to supply construction workers, one of the most common and least specialized professions in the oil industry. Senimdi Kurylys has a small office in Atyrau and a room in a container at the Tengiz rotation camp, hundreds of kilometers to the south.

Mussin has repeatedly accused Senimdi Kurylys of driving his company to bankruptcy through cheap subcontracting agreements.

“I told Senimdi Kurylys that my expenses [per worker] were higher than the per-head payment they were offering. So I asked them for more for the following years. They told me to agree to these figures first and they would raise the salary afterwards. But after three years working for them, they refused to increase the pay,” Mussin told Vlast.

The multimillion dollar contracts that TCO awarded to Senimdi Kurylys, in fact, translated into marginal revenues for companies, such as AOC, which effectively supplied the workers, Mussin said, because Senimdi Kurylys’s own tenders only accounted for low hourly wages and drove manpower agencies to push down worker compensation.

Mussin said he asked for help from the institutions for years. His cause only gained momentum in mid-2023, after he sent a letter to the Presidential Administration.

“The Presidential Administration responded to my letter. As a consequence, the prosecutor launched an investigation,” Mussin told Vlast.

In January 2024, the General Prosecutor’s Office found Senimdi Kurylys in partial violation of the labor legislation due to wage arrears, leave refusals, safety code violations, and “a disproportion in the payment of foreign and local workers.” The Atyrau Prosecutor’s Office confirmed to Vlast that the company was fined but didn’t disclose the amount of the fine.

Body Renting

Mussin leaked to the press a number of documents showing that Senimdi Kurylys paid local workers a fraction of what Senimdi Kurylys received from TCO: Hourly ranges in a 2019 contract between AOC and Senimdi Kurylys fluctuated from a maximum of $9/h for a welder and $7.7/h for an electrician, to a minimum of $6.1/h for cleaners and other workers.

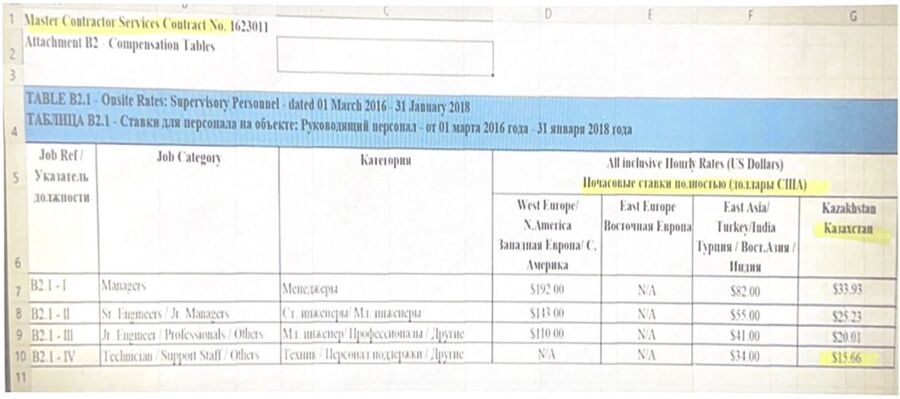

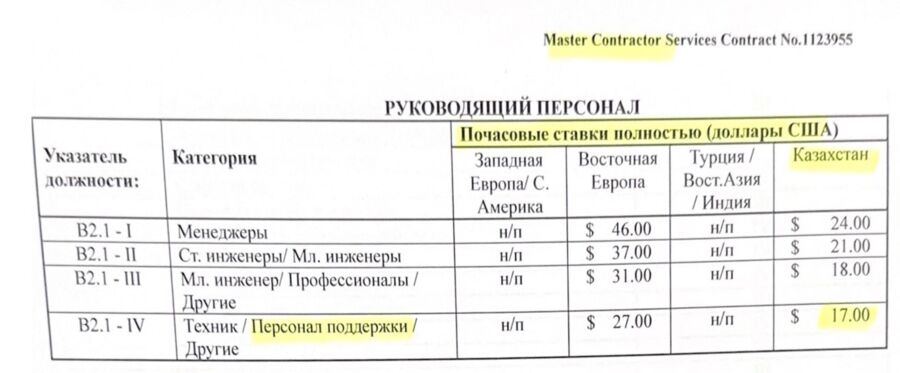

The minimum that TCO allocated to workers hired through Senimdi Kurylys in their 2016-2018 agreement was $16/h. Therefore, Senimdi Kurylys was earning a margin between 44-62% per AOC worker, Mussin argued.

While it is normal for contractors to mark up the subcontractor’s services, the margin that Senimdi Kurylys enjoyed was far too much, Mussin said.

“This is a process called body renting,” a manager at a western-owned manpower agency in Atyrau who asked not to be named for fear of retaliation, told Vlast.

“Because TCO has high requirements, only a few big manpower agencies can access their tenders. This, however, means that these agencies then can win large packages and subsequently subcontract for much less to other companies or smaller manpower agencies,” the source said.

In a written response to Vlast, TCO said its procurement system is fair.

“TCO has a transparent tendering system. [...] TCO tenders are conducted in accordance with established internal rules and procedures, ensuring equal conditions and opportunities for all participants.”

Aidos Koldasov, general director of Kazservice, a business association of oil and gas service companies in Kazakhstan, disagreed. He said TCO’s procurement system is skewed towards larger contractors, which eventually leads to a pay gap.

“We are not satisfied with Tengizchevroil’s procurement system because we don’t see it as transparent. The role of ‘general contractors’ is always played by foreign companies. Why can't local companies have this role? If the contracts were smaller, [local companies] wouldn’t need to always work in subcontracting mode,” Koldasov told Vlast in an interview.

“The problem of wage disproportion exists. And service companies have addressed this question to TCO,” Koldasov concluded.

Senimdi Kurylys didn’t respond to Vlast’s request for comments.

Saulesh Yessenova, a professor of anthropology at the University of Calgary, said that the contractors that win tenders would try to undercut their workers.

“The assumption is that, once you meet TCO’s requirements, the contract is awarded to the lowest bid, which also includes a kickback. This means that they save on worker pay and cheat the workers,” Yessenova told Vlast in an interview.

A former supervisor who worked for companies frequently subcontracted by Senimdi Kurylys, told Vlast that contractors control the entire workflow.

“The Turks [Senimdi Kurylys – ed.] decide who to hire, they have us on call at all times, but sometimes they just don’t call. Jobs are mostly assigned based on who’s your krysha [a Russian metaphor for ‘patron’]. Workers shift around according to the company that wins the contract. But sometimes Senimdi Kurylys puts either companies or workers on a black list and that’s the end of them,” said the source on condition of anonymity.

Yessenova said these processes are familiar to those who have studied worker issues in Atyrau.

“It looks to me that nothing has changed since the time I worked there. Senimdi Kurylys was deeply ingrained in the oil sector in Atyrau and at the epicenter of worker riots. It was never investigated and never punished. After the 2005 strike, the government set up an office at the site, a surrogate trade union, where people could go to file complaints about their work conditions. This is not the way to go, however. All that happened because there were no independent trade unions, because Chevron destroyed the trade union at TCO, turning it into a pocket union,” Yessenova told Vlast.

“The rest of the contractors, subcontractors, and sub-subcontractors are not unionized at all, there is absolutely no transparency and no way for workers to seek conflict resolution through legal instruments.”

Special Treatment

In theory, workers hired for a specific task through a manpower agency should receive a higher-than-average hourly compensation, compared to a regular salaried worker, because their expertise is only required for a limited amount of time, making their job more precarious.

Yessenova confirmed that contracting out jobs and tasks makes it easier to terminate contracts. “And this way, companies like Chevron are not responsible or liable, because contractors and subcontractors are independent entities.”

The documents that Mussin leaked showed in detail how the process of undercutting local workers is set up.

The table presented by TCO shows that the company divides workers into four “geographic” categories: 1) West Europe/North America; 2) East Europe; 3) East Asia/Turkey/India; 4) Kazakhstan. The fact that the salary range was “not applicable” in the “East Europe” column is an indicator that this is a format used also in other jurisdictions by companies like US-based Chevron, which leads the TCO venture.

A foreign manpower agency manager who lived in Kazakhstan for more than a decade, told Vlast this was a practice that TCO established years ago, first by differentiating between “expat” workers and then by assigning salary levels according to the country of residence.

“TCO first came up with the idea of ‘Expat-A’ and ‘Expat-B’, which led to salary cuts for the latter. Several people left the company at that time. Then, about nine years ago, TCO came up with another magic formula, which weighed salaries against the cost of living in the worker’s country of origin. That was an Excel spreadsheet with more than a hundred countries listed in detail,” the former manager told Vlast on condition of anonymity.

From managers to junior engineers, workers from “West Europe/North America” earn around 5.5 times more than local Kazakhstanis with the same job. Compared to workers from “East Asia/Turkey/India”, instead, local workers earn around 2.2 times less.

“In certain times, these gaps were wider. People from Kazakhstan would make $150/day compared to Western expats doing the same job for $1,000. If Kazakhs found out what foreigners really earned, there would probably be an uproar,” the source said.

Various sources also claimed that there is a widespread unwritten rule among large foreign corporations in the oil sector that local salaries could not be as high as the international standard, otherwise this would create a massive gap with the much lower average salaries outside the sector.

When asked about the salary disparity shown in the documents provided by Mussin, TCO said that they do not control salaries at contracting companies.

“Contracting companies are independent employers and independently determine the system of remuneration of their personnel and are responsible for their personnel and for compliance with the requirements of the legislation of the Republic of Kazakhstan,” TCO told Vlast.

When asked about this disparity, the Atyrau Prosecutor’s Office told Vlast that this practice is lawful.

“The contract between TCO and Senimdi Kurylys does not provide for the regulation of legal relations with subcontracting organizations, including the remuneration of their employees,” the prosecutor said.

TCO also argues this process is legal.

“TCO is a law-abiding company operating within the framework of [Kazakhstan’s] legislation. To perform work and provide services, TCO enters into relevant contracts with contractors, including Senimdi Kurylys,” a TCO spokesperson told Vlast in a written response.

In 2006, then-energy minister Bakhytkozha Izmukhambetov argued in Parliament that the previous rule obliged contracted companies to show the employees’ wages in the contract.

“This provision could lead to discrimination against staff whose salaries are fixed in the contract,” Izmukhambetov said.

At a meeting in Atyrau in 2014, Geir Nilsen, the trade union representative at Norway’s Statoil (now Equinor), said that in Kazakhstan wage calculations are counterintuitive, because they are only based on the country of origin of the worker, not on experience or qualifications.

“In Norway, this is impossible because there, industry salaries are regulated by the state with the participation of trade unions,” Nilsen said.

This is a long-standing issue in Kazakhstan, where local workers have been traditionally paid several times less than their peers from other countries, whether they are “expats” from the Global North or “migrant workers” from the Global South.

Academic literature increasingly considers colonialist heritage to be the driver behind the differentiation between “expats” and “migrant workers.” In most cases – including TCO pay scales, according to sources interviewed for this – companies set a salary according to the country of origin, rather than skills or experience.

Locals, however, seem to continue to be shortchanged. In a 2018 email recently leaked in the Caspian Cabals project led by ICIJ and seen by Vlast, TCO managers said they audited some of their contractors and found that two of them violated their “minimum wage requirements,” preparing a “notice to comply with immediate effect and repay all historic under-payments.”

A Widespread Issue

In Atyrau, a local worker expressed his dissatisfaction with this discrimination, and this led to his firing.

“When I worked in Kashagan, our people were making 10 times less money than foreigners. Workers were not allowed to talk about salaries. When I brought up this issue, I was fired,” the worker told Vlast on condition of anonymity.

Yessenova said that the business-focused approach by the government weakened labor rights.

“At the beginning, the central government wanted the local government to support business, but they didn’t say how. And so the local government interpreted it as a permission to close their eyes on labor issues,” Yessenova said.

Trade unions grew weaker in a context of diminishing rights. The Labor Code was modified a decade ago, together with the law on trade unions, in the aftermath of the bloody repression of a worker strike in the western oil town of Zhanaozen in 2011. These changes cemented the companies’ supremacy: Workers could be fired without explanation or just cause and the right to strike was further limited.

In most cases, especially at projects operated by trans-national companies, workers are discouraged from joining trade unions, a clear violation of the principles established by the International Labor Organization (ILO) and that Kazakhstan signed up to.

ILO’s Convention n. 98 says that “workers shall enjoy adequate protection against acts of anti-union discrimination.”

And safety is an issue as well. In a 2017 email seen by Vlast, TCO managers said they stopped work with one contractor for “unsafe work at height” and were drafting a letter to the contractor using language “from the similar letter we sent to [another contractor].” This highlights how frequently contractors and subcontractors bypass safety measures that TCO considers the bare minimum.

Running out of Gas

According to TCO, the massive expansion project that has lasted for the last eight years and cost around $37 billion is on track to be completed in the first half of 2025. When the so-called Future Growth Project (FGP) is over, however, most of the construction sites and plans would shut down, creating a worker surplus.

“With FGP stopping, there are going to be a lot more unemployed locals. Some of them will end up working abroad, in the Gulf countries for example, where they are considered cheaper than most expats,” the former manpower agency manager said.

“The work conditions of full-time employees as opposed to contractors or subcontractors are markedly different,” the former supervisor in Tengiz, said.

In the case of subcontractors, “money gets eaten up by the time it reaches the worker,” he added. “The subcontractors only get crumbs. It would be great if contractors did not eat up the money in the middle and people were hired directly, it would be good for our people.”

Observers noted that the government is now pressuring TCO to avoid laying off workers and contractors at a fast pace, because this would cause a shock to the work environment of the Atyrau region.

But the strategy of hiring “too many workers” has its drawbacks, Yessenova argued.

“When I was doing research around Tengiz, TCO had no idea how many people were working there, how many companies were working there. This created an unsafe situation at the workplace. It was a mess,” Yessenova said.

“Although they would try to sell you the idea of subcontracting as ‘efficiency’, in reality, this translated into too many workers earning too little, without job security or workplace safety. And TCO has zero liability for whatever is happening. Chevron is like a little god sitting on a bunch of money and resources, and it’s untouchable.”

Almas Kaisar contributed to the story.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.