Despite the growing problems in global politics and economics, Central Asian countries can improve their position, Beata Javorcik, Chief Economist of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development believes. In an interview with Vlast, Javorcik said that Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan’s multi-vector foreign policy gives them the opportunity to bridge contentious economic blocs. This makes them an attractive destination for investors from many regions and countries: from Western Europe to China and the Middle East.

Yet, Kazakhstan still grapples with the long-term goal to diversify its economy. Javorcik argues that despite unsuccessful attempts at reindustrialization the country can pull through. According to her, Kazakhstan’s highly educated population could turn the country into a major exporter of services, because the salaries of skilled workers here are still lower than in developed countries.

Читайте этот материал на русском.

Are we facing a global economic crisis? What will be the consequences of the decisions made by US President Donald Trump's administration? Just how will this ‘new normal’ reshape the global economic system?

The global context remains fluid, these are times of heightened uncertainty. The pandemic was a situation of unprecedented uncertainty and we had hoped it was going to be over. But then a war against Ukraine started, then the conflict in the Middle East. And now we are witnessing frequent policy changes by the new US administration. This means that we’ll remain in this uncertain context for the foreseeable future.

Over the last two-three years, we have seen advanced Western European economies have performed poorly, even diverging from the trends seen in the US. In particular, Germany’s GDP shrank. The situation is quite fluid.

When you think about medium to longer term trends, we see the World Bank upgrading the growth potential of the US economy. There are big question marks about the European Union’s future competitiveness. In our report Regional Economic Prospects we analyzed 2,000 companies with the largest research and development spending. And we noticed that more than a third of these firms are American. A quarter are Chinese, and only a fifth comes from the EU or the UK. That's a very different picture from 20 years ago, when European firms were investing in R&D more than American ones, and China accounted for only 5% of the total.

Additionally, global growth has remained relatively stable over the past three years, but it's modest by historical standards. The world used to grow faster than it is growing now.

What’s in store for Central Asia?

Among the places where we work, Central Asia is registering fast growth rates. Last year, it grew twice as fast as the average of all the countries we monitor. Central Asia’s GDP grew by 5.2%, while the EBRD average was 2.7%.

Over the last ten years, we saw a greater synchronization of business cycles in the rich countries and emerging markets we monitor. Dependency on German exports was a negative contributor to growth in Central Europe, in Western Balkans, and even in North Africa. Central Asia, by the virtue of being further away, was less exposed to that trend.

We expect growth at 5.7% this year and 5.2% next year In Central Asia. That’s faster than, say, China.

Sources of growth are internal: increases in real wages drives private consumption. And in Central Asia wages are growing faster than in the pre-COVID period. Conversely, in Central Europe wage growth has been slower than the pre-COVID trend.

Public investment is also a driving force in some countries. And here commodity exports matter. For instance, Kazakhstan’s mining sector last year showed a weaker performance. Yet, remittances in some Central Asian countries remain strong. And for tourism we witnessed a post-COVID rebound, with some countries even registering a record level of inflows.

Do current geopolitical tensions and global economic downturns, including inflationary trends, affect Central Asia?

First, we have reported a slowing of inflation over the past two years, but our last report shows an uptick. We are now no longer on the path of slower inflation. One of the factors is wage growth, another is higher energy prices being passed down onto household budgets. In the countries where we operate, faster inflation immediately leads to more costly utility bills.

Second, there is a question of exposure. Everybody is wondering how US policies may affect the rest of the world. President Trump keeps talking about tariffs. In our Regional Economic Prospects report, we did a very simple back of the envelope calculation: What if the US introduced a 10% tariff on all goods? Essentially, our regions of operations would not be highly exposed. The three countries that have the highest exposure are Jordan, Slovakia, and Hungary. And even for them, the impact on GDP would be on the order of 0.3 – 0.5%. Central Asia is less exposed.

What’s going to matter more is the indirect impact of the performance of advanced European countries, particularly Germany. For Europe as a whole, the US is the largest export market. Now, 20% of German car exports go to the US. It's incredibly difficult to assess the impact of tariffs, because what matters is not just your tariff, but where you are relative to others.

Does that mean that the new US tariff policy will not greatly affect Central Asia?

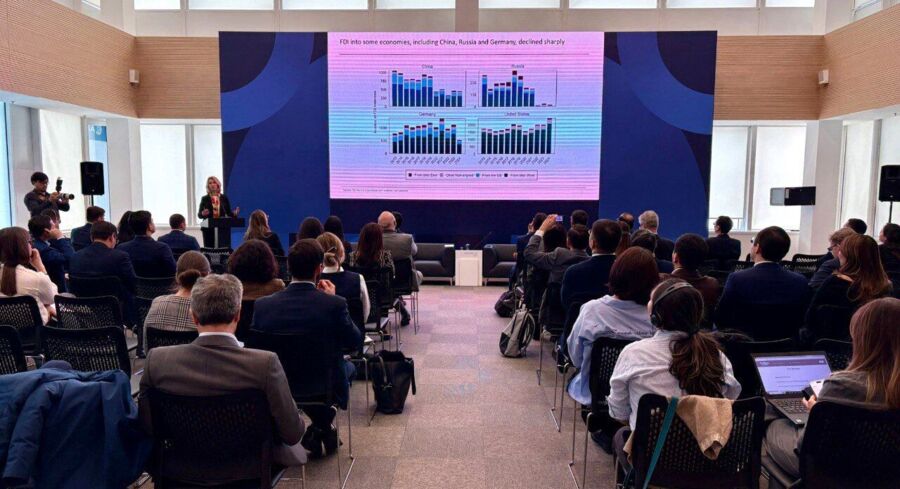

This fluid geopolitical context may be actually good for Central Asia. We used to talk about fragmentation, that is, the possibility of the world splitting into blocs. Now it's more accurate to talk about reconfigurations. The “Western bloc” is no more. In our report we analyzed data on inflows on a number of greenfield FDI projects, facilities that are built from scratch. This is a very good indicator of investor sentiment.

We saw Russia getting close to zero FDI. Also, there was a big drop in FDI going into China, because of dwindling interest from American and Western European investors. Conversely, we saw India and Vietnam getting a lot of FDI. The same goes for the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan also saw an increase.

What the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan have in common is that they are seeing FDI inflows from everywhere, from the West, from China, and from the Middle East. In other words, this multi-vector geopolitical strategy of trying to be friends with everyone, helped these countries become more attractive for FDI. The IMF coined a new term calling them “connector countries”. These countries could sell more logistics services and become an alternative trade route between east and west.

What are the risks that EBRD sees specifically here in Kazakhstan?

As a big commodity exporter Kazakhstan is vulnerable to fluctuations in, say, oil prices. The OPEC+ group recently decided to increase production, which will translate into lower oil prices.

A second short term risk is the slowdown in China, driven by a potential US-China trade war. China matters because it’s a big commodity buyer.

And the world continues with green transition and decarbonization policies. Of course, the future of hydrocarbon exports is less rosy, so alternatives are needed.

Kazakhstan’s president announced a new national development plan, which is supposed to double our GDP. What’s your understanding of this set of reforms?

The plan involves the desire to bring in more FDI, especially through liberalization and increased competition. There are privatization plans for some state owned enterprises. The plan also focuses on stronger property rights and a predictable business environment. The ingredients are there, but what matters is the actual implementation.

FDI has driven the development of Central Europe and other countries of post-communist space, because FDI is not just money, It's knowledge, technology, and access to foreign markets.

So far, the export of services has primarily been driven by foreign firms. Investment promotion is also a marketing strategy, which helps provide information to foreign investors, so as to lower information barriers and entry costs.

In our transition report we show the importance of openness: Once you allow FDI inflows, foreign players can bring in competition and improve the country’s export position. We stand ready to help with privatization plans.

Which sectors would be more interesting for you?

We both invest and provide advice. We’ve helped in many countries. The EBRD is a proud owner of a 5% stake in Air Astana.

According to our strategy, we don't do “old energy.” We rather focus on renewable energy. Our investments support the green transition.

You mentioned Kazakhstan’s multi-vector policy. At the same time, we see foreign investors feeling pressure from the government, as is the case with the fines and arbitration proceedings involving oil companies working on the Kashagan project. Is this consistent with the multi-vector policy?

Investor servicing is key, committed investors need to be helped. One of our functions is being an advocate, serving as an intermediary between investors and the government. In the case of Kazakhstan, the Foreign Investor Council serves this purpose.

Disputes happen, it’s normal in business. It’s important to reach an agreement and to create a predictable environment for investors.

Is Kazakhstan trapped in a dependent position within the global economy? We rely on oil exports and we don’t have enough agency to withstand price fluctuations.

For resource rich economies, diversification is a decades-long challenge. But it is achievable, because you can use revenue from these resources to support a diversification policy. However, now it is much harder for countries other than China to start exporting goods they never exported before.

Since the global financial crisis of 2008, exports of manufactured goods alone has not been enough for growth. So what are the alternatives? For a country like Kazakhstan, exports of agricultural products particularly to the Chinese market could be a possibility.

In the longer term, countries [like Kazakhstan] could focus on exporting renewable energy and services. Central Asia, for example, has yet to jump on the bandwagon of computer services exports.

Importantly, many post-communist countries manage to do this through education. Firms engaged in sectors such as computer services ask for skilled workers with advanced degrees. And while wages of low skilled workers here are not competitive compared to China, the wages of highly skilled workers are more competitive than in Western Europe.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.