The year 1995 marked a major turning point in the history of contemporary Kazakhstan. In just one year, then-President Nursultan Nazarbayev dissolved the Supreme Council, extended his powers through a referendum, imposed a new Constitution, and created a fully controlled parliament.

This way, Nazarbayev laid the foundation of a super-presidential form of government, which remains valid in Kazakhstan to this day. By centralizing power in his own hands, Nazarbayev facilitated the privatization of strategic assets, mostly for his own personal benefit.

1991-1993 Transition

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Kazakhstan maintained the Supreme Soviet, a government organ inherited from the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic.

At the time, Nazarbayev had made the transition from being the leader of the KazSSR to becoming the president of independent Kazakhstan.

In 1993, with the first Constitution, the Supreme Council replaced the Supreme Soviet. And this is when Nazarbayev’s conflict with the Council started, according to the former president’s autobiography “My Life: From Independence to Freedom.”

In his 2023 book, Nazarbayev wrote that the conflict began because the Supreme Council made it difficult to carry out unpopular reforms in Kazakhstan’s shift from the Soviet Union’s state-controlled economy towards a market economy.

According to Tulegen Zhukeyev, who served as deputy chairman and secretary of Kazakhstan's Security Council during the early years of independence, Nazarbayev’s focus on centralizing power laid the foundations for this conflict.

“Nazarbayev's actions took the form of an anti-parliamentary and anti-constitutional upheaval. Then he cracked down on opposition, held choreographed referendums, and orchestrated his early re-election as president,” Zhukeyev said.

Vitaliy Voronov, former deputy of the Supreme Soviet (until 1993) and presidential aide for relations with the legislative body from 1990 to 1994, explained Nazarbayev’s motivation, saying that Parliament was a strong institution of public control over the executive power.

According to him, the Supreme Soviet was composed of people with a popular mandate, which could be withdrawn in case of poor performance. The Supreme Soviet determined the composition of the government and the judiciary, and it could control economic policy and state finances.

“This interfered with the agenda of the executive branch [that is, the president] to carry out reforms unchecked,” emphasized the former deputy.

Some deputies opposed the radical market policy switch known as “Shock Therapy,” which was based on extensive and uncontrolled privatization of state assets, price liberalization, deregulation of the labor market, and cuts to social guarantees.

The implementation of these reforms negatively affected citizen welfare, leading to increased poverty and mass unemployment. In turn, by 1995 Kazakhstan's GDP had lost more than 40% compared to 1990, and inflation during this period increased between 1,000 - 3,000%.

Because of public dissatisfaction, the deputies tried to mitigate the effects of shock therapy. This pitted them against Nazarbayev, who seemed unbothered by the real-world consequences of his own decisions.

According to Voronov, in order to overcome the Supreme Soviet’s resistance, Nazarbayev orchestrated the self-dissolution of the Supreme Soviet by luring some of the deputies into government positions.

The Supreme Soviet was thus dissolved under the guise of a transition to a more “professional” parliament, which would rubber-stamp government bills without lengthy discussions.

At the same time, deputies offered little resistance to the dissolution of the Supreme Soviet, said human rights activist and journalist Tamara Kaleyeva, who then covered judiciary issues for the “Kazakhstanskaya Pravda” newspaper.

“No one back then was adept at political intrigue and backstabbing. They just did their job. But they were cleverly outsmarted.”

Ultimately, the dissolution of the Supreme Council in March 1995 gave Nazarbayev full reign to rule by decree. This laid out the legislative basis of the forthcoming privatization campaign.

Elections for a new, more controlled Parliament were only called in December 1995.

Fearing opposition from the new assembly, in 1996 Nazarbayev ruled that he would need to have a final say on legislative changes. This turned Kazakhstan into a country with a super-presidential form of government.

Parliament as an Obstacle

During the first years of his rule, Nazarbayev said that, without rapid and painful changes to the economy, the country would continue to decline. In his 1990 book “Without Rights and Lefts,” he insisted that any political fight, especially within the walls of the Supreme Soviet, would only slow the recovery from the crisis.

In an interview to “Kazakhstanskaya Pravda” in summer 1993 he said, “Unless the executive branch becomes stronger, things are not going to go our way.” He also initially assured that he would not act against the Supreme Council.

However, the conflict between the two powers only intensified until Nazarbayev’s decision to dissolve the Supreme Council in 1995.

According to Voronov, the standoff began when Serikbolsyn Abdildin, an independent politician who openly opposed Nazarbayev, was elected Chairman of the Supreme Council.

“We nominated Abdildin, but Nazarbayev tried to halt the election. Deputies contested the president’s intervention, and Nazarbayev remembered this,” said the former deputy.

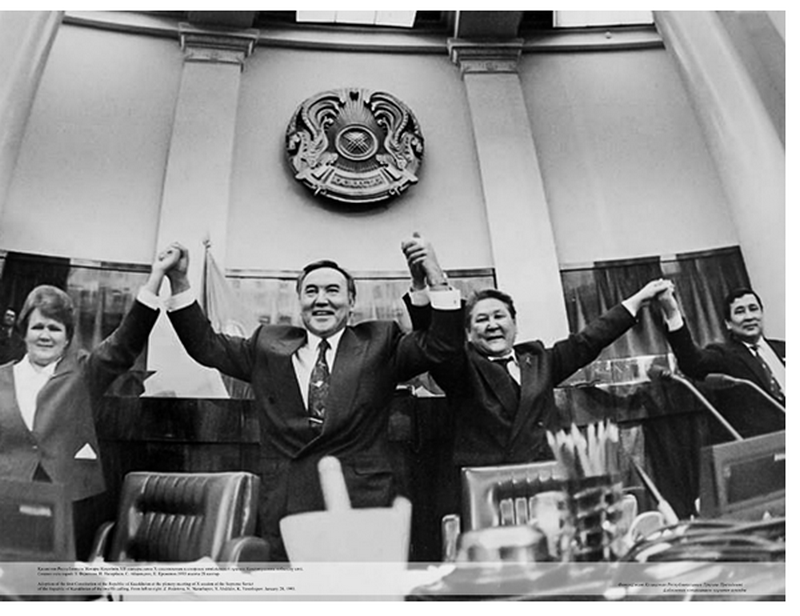

The conflict encouraged the adoption of Kazakhstan’s first Constitution in January 1993.

“Both Nazarbayev and the Supreme Council applauded the event. Nazarbayev said that the people of Kazakhstan authored the Constitution. But he was not fully satisfied with the outcome,” Voronov said.

In Nazarbayev’s opinion, this document created conditions for dual power, putting the legislative and executive branches on the same level.

“This way, budget approval and government formation turned into a nightmare,” Nazarbayev wrote in “My Life.”

He believed that he was leading the transition to the market economy and therefore should have the final word. At the same time, from his point of view, the Supreme Council maintained a Soviet mindset and hampered the transition.

Kaleyeva said she repeatedly witnessed how deputies challenged executive decisions that they believed would negatively impact citizen welfare.

“There were many fierce disputes regarding social support and guarantees. Deputy Vladimir Chernyshev argued that wages were [too low] and that it was impossible to live like that. Naturally, he was supported by many deputies.”

In 1994, the Supreme Council gave a vote of no confidence to the government's policies.

“The legislative branch was trying to prevent an unbridled privatization process,” Voronov said.

In his book “The Post-Soviet Political Regime of Kazakhstan,” political scientist Dmitri Furman wrote that at the time the opposition had built the “Respublika” coalition, headed by Abdildin.

The opposition planned to discredit Nazarbayev’s ploy to rule the country unchecked.

Throughout 1994, the opposition put forward proposals to limit presidential and executive powers in terms of selling state property and attracting foreign loans. They also proposed a judicial audit of the first wave of privatization. The opposition also planned to nominate a candidate for the next presidential election.

“Voluntary” Self-Dissolution

Recognizing the opposition’s growing influence, Nazarbayev proposed to replace the Supreme Council with a “professional parliament,” that he could control.

Furman noted that Nazarbayev refused to directly eliminate rivals because he feared the conflict would escalate into violent clashes, something that happened in Moscow in 1993, when Russia's then-President Boris Yeltsin sent military tanks to shell the parliament building.

In his book “My Life,” Nazarbayev said that the transformation of the Supreme Soviet was necessary because the deputies were incompetent.

Former deputy Zhukeyev argued that there was an objective need to restructure the legislative branch because most of the 350 deputies were representatives of the industrial and administrative elite.

“350 deputies — that’s a lot. Many of them were ignorant, and their work was unstructured. But Parliament would have inevitably become more professional through time, there was no need for Nazarbayev to intervene,” said Zhukeyev.

In her time as a reporter, Kaleyeva noticed that, despite the lack of expertise and political experience, the parliamentary assembly was an open place that journalists or citizens could attend.

In “My Life” Nazarbayev wrote that being at odds with the executive was convenient for the Supreme Soviet, because they could blame the deteriorating economic situation on the president.

Voronov, however, said the opposite. He argued that, at the time of independence, Nazarbayev had become the most popular politician not only in Kazakhstan but in the entire Soviet Union.

This widespread support, Furman wrote, allowed Nazarbayev to manipulate citizens' opinions by redirecting their frustrations towards the Supreme Soviet.

“The voters were blaming us for the growing poverty. They told us: ‘It was you who dissolved the Soviet Union,’” Voronov said.

Elite pressure pushed many deputies to side with Nazarbayev during the conflict with the Supreme Soviet, which eventually voted to self-dissolve, allowing Nazarbayev to abolish the institution.

Publicly, Nazarbayev requested the Supreme Soviet to relinquish the authority to manage the economy, but he really aimed to strip its authority to appoint key ministers, the chairman of the Central Bank, judges, prosecutors, and heads of local executive bodies.

Voronov and his fellow deputy Aleksander Peregrin published an appeal to save the Supreme Soviet in the “Respublika” newspaper. The issue was urgently printed the night before the final session was held.

“Before the session started, Nazarbayev said to me in the corridor: ‘Vitaliy, you are my assistant, why are you trying to hold me back?’ I replied that my job was to help the president, but without violating the Constitution. And then the meeting began, and the deputies agreed to self-dissolution,” Voronov said.

“It Was Unconstitutional”

In March 1994, elections were held for the new Supreme Council. Although the number of deputies was reduced from 350 to 177, the new legislature was still slow, according to Nazarbayev. He then decided to accelerate the transition to a “professional parliament.”

In March 1995, journalist and Supreme Council candidate Tatyana Kvyatkovskaya published an article exposing procedural violations during the elections. The Constitutional Court declared the election results invalid.

At the same time, journalist Kaleyeva noted that without a top-down direct instruction, the Constitutional Court could not have made such a decision.

“Neither Chairman Murat Baimakhanov nor any other judge irrefutably believed that the law is above everything. All of them were stuck in the Soviet era. None of them would have put up a fight for their beliefs,” Kaleyeva said.

It was only following Kvyatkovskaya’s exposé that the Supreme Council was dissolved and abolished.

“I remember seeing the tears in Abdildin’s eyes when he heard about the decision to liquidate the Supreme Council. Yet he was one of those who had agreed to self-dissolution [of the Supreme Soviet] in 1993. It seems that many deputies paved the way for their own overthrow,” Kaleyeva said.

Furman wrote that the deputies did not strongly resist Nazarbayev because some were demoralized by the 1994 elections, while others were promised new jobs in the positions of power.

Several deputies went on hunger strike and refused to leave their offices, but their electricity and phone lines were cut off, and they were eventually escorted off the premises under the pretext of renovation in the parliament building.

Chernyshev, the most principled opponent of Nazarbayev's agenda, only gave up after he was severely beaten by unknown persons.

Ordinary citizens, according to Kaleyeva, paid little attention to these events. The importance of the Constitution and the legislature for them had been devalued during the Soviet era. People perceived deputies as government puppets.

“At that time, businesses were closing down, thousands of people were losing their jobs. Most of us had not been paid our salaries for six months or even a year. In my editorial office, they paid me in canned meat and bags of beets and carrots. People simply did not care about the Supreme Council. Everyone was in a state of shock, trying to survive,” Kaleyeva said.

Rapid Privatization

Recommendations from the International Monetary Fund to sell state assets well matched the government’s privatization drive.

In his 2018 book “Neoliberalism and Post Soviet Transition: Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan,” researcher Wumaier Yilamu writes that shock therapy was a condition for obtaining an extended credit line and attracting foreign investment to support Kazakhstan's economic transition.

Nazarbayev's shock therapy sped up Kazakhstan’s market transformation. But this was still not enough to meet IMF conditions.

The state still held a 75% share in the economy. To reduce it, the government planned to privatize around 37,000 enterprises.

After the Supreme Council disbanded in March 1995, the Constitutional Court confirmed Nazarbayev’s right to assume the powers of parliament under a law passed as early as 1993. This meant that the president could issue decrees with the force of law.

At the same time, a new parliament could be convened when the president deemed it necessary.

In the meantime, in August 1995, Nazarbayev devised and ratified a new Constitution.

Parliamentary elections were eventually scheduled for December 1995. Nazarbayev ruled without a parliament for about nine months.

In “My Life,” Nazarbayev claimed that in this period, he passed more than 140 “market-oriented laws” through decrees.

“Of course, we used this tactic only until the election of the new parliament. It was not excluded that the laws enshrined at the same time by my decrees and enacted at the same time might not be supported [by parliament],” he writes.

Voronov explains that legislative powers were essentially transferred to Nazarbayev, who changed almost all legislation by decree.

“In fact, he built a whole new constitutional order,” the former deputy said.

As he continued to push for market reforms, Nazarbayev's personal power grew.

Immediately after the abolition of the Supreme Council, Nazarbayev established the Assembly of People of Kazakhstan, a body under his direct control in lieu of parliament.

Pretending to answer a “request from the people,” the Assembly formally asked Nazarbayev to hold two referendums: one to bypass elections, extending his presidential powers until 2000 (29 April 1995) and another to adopt a new Constitution (30 August 1995).

According to official data, both referendums were approved with more than 90% of the votes. This allowed Nazarbayev to expand his powers.

Deputies of the new parliament convened for the first time in January 1996.

The new parliament, which convened in January 1996, according to Voronov, was a well-controlled and compact institution with 131 deputies (67 deputies in the Majilis and 64 deputies in the Senate) rather than 177.

Nazarbayev's rule by decree and a more accommodating parliament made it possible to push for the privatization of strategic state assets.

The number of large enterprises subjected to privatization increased from five in 1995 to 166 in 1997-1998. Among them were Zhezkazgantsvetmet (now Kazakhmys), Karagandashakhtougol (later ArcelorMittal, now Qarmet), Mangistaumunaigas, Kazakhtelecom, as well as the enterprises later consolidated under the Eurasian Resources Group.

EBRD data show that, as a result of accelerated privatization, the share of the private sector rose from 25% to 60% of Kazakhstan’s GDP by the end of 1999. Thereafter, the rate of privatization slowed down and almost halted.

“[Privatization] caused big problems, big scandals… The process took place in the most concealed way, sometimes disguised through offshore companies. The true owners remained in the shadows,” writes economist Arystan Yesentugelov in his book “The Economy of Independent Kazakhstan: The History of Market Reforms.”

Yesentugelov noted that Nazarbayev was in a hurry to introduce market mechanisms because their effect could have encouraged his adversaries to repeal the reforms and return to the previous, state-driven welfare system.

According to Yesentugelov, Nazarbayev and his team of reformers failed to ensure a just privatization.

Nazarbayev, according to former deputy Zhukeyev, was offered different privatization options, but he chose the route that best suited his personal interests.

“By eliminating the Supreme Council and establishing a one-man rule, Nazarbayev realized that he could take assets for himself. He transferred some assets to pseudo-businessmen who were not independent. In doing so, he was able to extract money through them for his own purposes,” Zhukeyev said.

In his 2006 book “Central Asian Economies Since Independence,” economist Richard Pomfret states that during the second wave of privatization, state assets became concentrated in the hands of elites: oligarchs, entrepreneurs, and family members close to the president.

Several of them were later found in Forbes’ list of the 50 richest businessmen in Kazakhstan.

An edited version of this article was translated by Zeina Nassif.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.