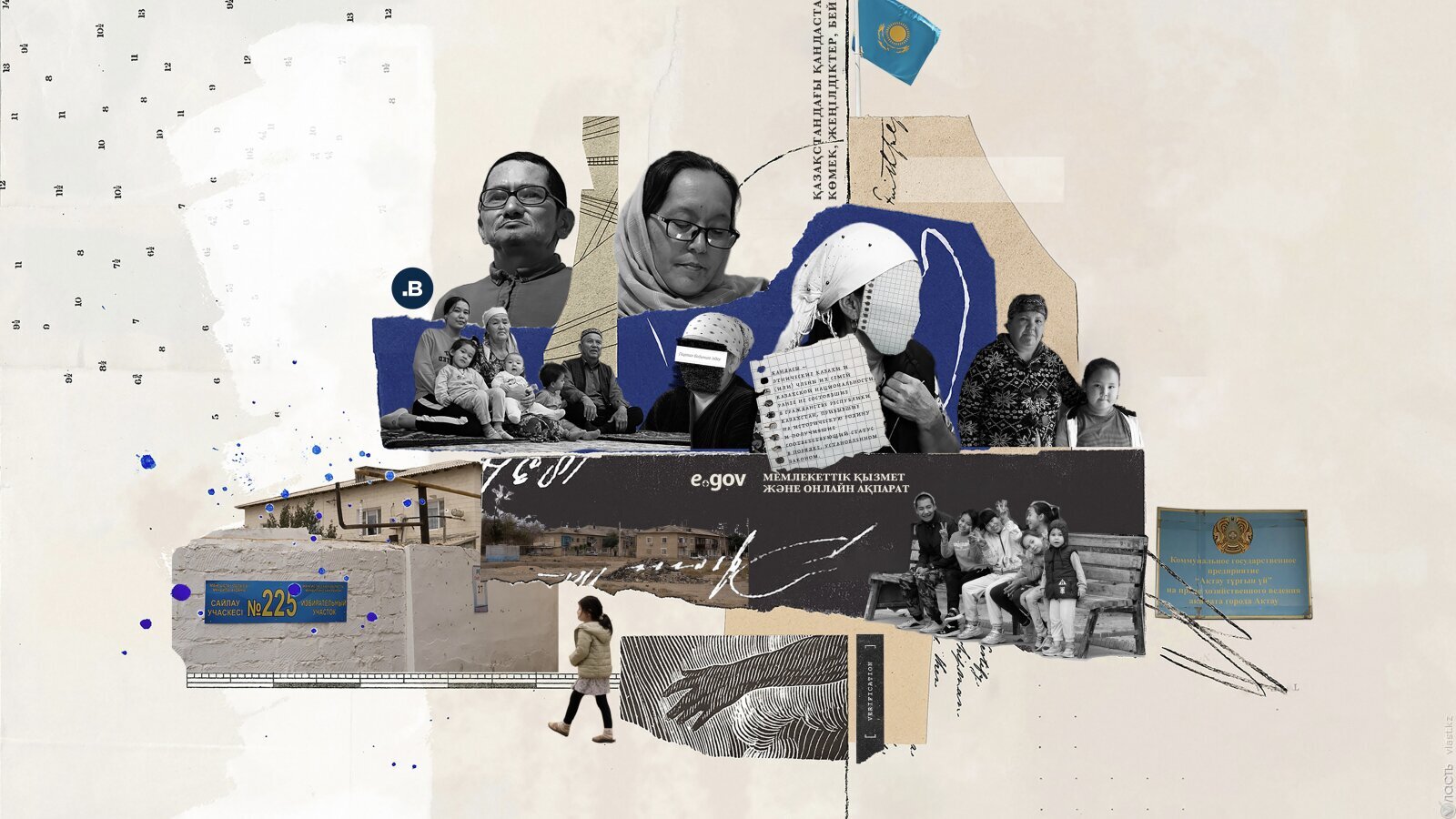

Hundreds of thousands ethnic Kazakhs “came back” to their homeland for the past three decades. Some hailed from other ex-Soviet republics, such as Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, others from faraway Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. While the returnees were initially welcomed in the regions of Kazakhstan where their ancestors lived, the most recent waves have faced a hostile bureaucracy that would have forced them to move to the north of the country.

Once known as “Oralman” (in Kazakh, ‘returnee’), ethnic Kazakhs who move to Kazakhstan are now defined as “Qandas” (in Kazakh, ‘compatriot’, literally ‘same-blood’). Around one hundred thousand Qandastar settled in the western region of Mangistau, a desert area tucked between the Caspian Sea and the Kazakh steppe.

Us versus Them

In Aktau, the capital of Mangistau, the government-sponsored office responsible for Qandastar is located inside the building of the Atameken business association, in the outskirts of the city. Locals know this place as “the House of Oralman”, although the label says “Aktau Housing”. At the back of the building, two dormitories house several families of Qandastar.

One of the locals opened their door to us, they were in a rush, late for a “toi”, a family celebration.

“I am disabled. Until recently, I lived near the Mangyshlak railway station. It’s a bit far from the city and then we got offered a place here. But what are the conditions? The apartment’s floor is in decay, light bulbs and the TV were snatched out. In other apartments, former tenants even pulled out toilets,” the woman living in the apartment said. “These flats are supposed to be assigned to us, but they did not give this one to me, I just applied for it and got it. There are families here where both parents work and they continue to live here, Oralman people too, what is this mess?”

The tenant complained of the disorganization because this kind of accommodation, on paper, should be reserved for single-parent families, people with disabilities, and orphans. She thought it was unjust that Qandastar also received social help.

On another floor, Svetlana Yergozhayeva invited us into her flat. There was a heavy smell and an elderly man covered with a blanket. Svetlana said she has not yet managed to find a cure for her husband, who is severely ill. She obtained the flat years ago because of her disability.

“There was nothing here. We fixed it up all by ourselves,” she said.

Upon their return from work, we met Golbibi Adai and her husband, Kadeh Soleiman. They are Qandas from Iran. In our conversation, the words “homeland” and “roof” resonated often.

“In 1929, at 16, my grandfather left Mangyshlak and moved to Gorgan, in Iran. He left because of the famine and repression. My father, six of my brothers and I were born in Gorgan. They are still there, while my little brother and I decided to come here. I was always interested in Kazakhstan, I wanted my children to grow up here,” Kadeh said.

For Kazakhs living in Iran, however, the path to return to the homeland is difficult.

“The consulate in Gorgan does not issue visas. But it’s quiet there and nobody protests. There are several Kazakhs and Turkmens in our city. Kazakhs in general are mostly based in three cities in the north of Iran, we all know each other and most of us are relatives to each other. We are not that many and we do not marry our children to other nationalities,” Kadeh added with pride.

Golbibi and Kadeh said that the “house, jobs, and conditions” that they were promised when they went to the Kazakhstani embassy were not provided in the end.

The couple and their children have lived in Kazakhstan for more than a decade. They were recently given an eviction notice for failing to keep up with rent. Their spot is now being claimed by other residents in need.

As a solution, the government offered Golbibi and Kadeh to move to the north of the country, but Kadeh said his family will have a hard time adjusting to the cold climate and widespread use of Russian language there.

“Iran is very warm, practically without snow or frost. I will have trouble working in the cold north and getting used to the language will be difficult. They tell us to go back to Iran, but why? My children are here. We, Qandastar, in general only need affordable housing. Once this is resolved, we can live here in peace,” Kadeh said.

Before we could leave their flat, Golbibi and Kadeh shared some traditional Kazakh greetings and gave us bread for the road.

Resettlement District

The Munailinsky district was established in 2007 near Aktau to host the wave of Qandas moving to Mangistau. According to local sources, more than 80% of the residents are immigrants. Several villages, now counting up to 40,000 residents, popped up. One of these is Batyr, a 10,000-strong settlement where people in line for social housing as well as Qandas (through the Nurly Kosh state program) were housed.

Local Kazakhs, born in Mangistau, have a two-sided attitude towards their Qandas compatriots. “If they are already here, there’s nothing we can do,” one said sluggishly.

A former construction sector specialist, having learned that our reportage focused on Qandastar, said that we should have paid attention to the locals instead.

“Why don’t you write about us? We face unemployment, low wages, inflation. They came here thinking they could work in the oil sector, but there are no more jobs. Mangistau is full,” said the man. “Qandastar are like Russians fleeing to our country after the mobilization,” a taxi driver told us.

The villages around Aktau lie in the bare fields of Mangistau, dotted with cranes and construction workers. We reached the center of Mangistau (formerly Mangyshlak), the closest railway terminal to Aktau. The settlement is subdivided into neighborhoods, with a bustling core at the center, near the bazaar and the train station.

Agriculture and short-term gigs are the main source of employment here. Several people commute to Aktau to work.

At the bazaar, we meet Nurzhamal Serikbayeva, a trader of camel milk and other products. Originally from Karakalpakstan, she moved to Kazakhstan in 2002.

The Serikbayevs had five children. According to the government quota, they received a migration bonus of 120,000 tenge (around $800 at the time).

“Several of our relatives had moved before us, so we followed. At first, it was difficult, because to buy land you needed to pay at least a thousand dollars. So we were living in a one-room apartment. We were then given additional government funds and could build ourselves a house. Through the employment center, I found a job as a security guard and worked there for 15 years. Now, I’m working in this market,” Nurzhamal said.

The economic situation, however, has worsened, according to her. ”People struggle to save money, everything gets paid from loan to loan.”

Deceived

Crowding a small, temporary hut are Karlygash, her three children, her mother, and Marat, a Qandas who moved 15 years ago helping them with accommodation and bureaucracy. Both Karlygash and Marat requested their names to be changed in this story.

Marat said he was treated well in Turkmenistan, but longed for his homeland.

“The Turkmens were nice to us. But because many Kazakhs had started to move back there were fewer options to marry our children to other Kazakhs. It is difficult for us to let our daughters marry other nationalities,” Marat added.

He then turned to Karlygash and her family, describing the injustice they are facing.

“They are being sent to Pavlodar, this is vile and unexpected. They already sold their homes in Turkmenistan and delisted from the registry. They were invited to come here fraudulently and now they are sent to Pavlodar,” Marat said.

Pavlodar is a city of 350,000 near the border with Russia, thousands of kilometers away from Mangistau.

“We lived well, my husband and I used to graze cattle for a farmer. We recently decided to move only because we wanted to be closer to our relatives. We were told we could move to Zhanaozen, but they gave us a visa with a stamp for Pavlodar. When we arrived to Mangistau, they didn't allow us to register. They didn’t allow our children to enroll in school,” Karlygash said.

According to Marat, the process lacked transparency.

Karlygash agreed: “When they gave us the Pavlodar registration card they told us not to worry, that we could stay in Mangistau without problems.”

For Qandastar, Pavlodar is both far and unfamiliar. “Those who went found little to no assistance and some are even coming back now,” Marat said.

This kind of injustice appears to be systematic. Karlygash’s neighbor also returned from Turkmenistan recently. She is in her 50s.

“We came back here because we wanted to return to our homeland. Because of quarantine measures, we barely made it here. We were promised that we could register in Mangistau. Instead, they gave us a registration card for Pavlodar,” she said.

Moving to the Homeland

Bekaly, an elderly Qandas, lives in a nicer house nearby and invites us to come inside. Sitting on the living room’s carpet, he told us his story.

“I was born in 1942, my relatives had escaped the famine a decade earlier. They worked for decades in agriculture in a Turkmen village and then decided to come back to Kazakhstan. This is our land, where our ancestors are buried. The Turkmens didn’t send us away, they are good people just like us,” Bekaly said.

“We just arrived here and they told us to go to the north. Why would I go to the north at 80? Here, I go out in the morning and take nice walks. We don’t need help here, just the basic support,” he added.

Despite the initial difficulties, Bekaly said he felt welcome in Mangistau. He asked us if we understood him well. He feared that his Kazakh was not clear enough.

Without administrative restrictions, Bekaly is sure that at least 50 families he knows in Turkmenistan would move to Mangistau.

“We thought we would come to Kazakhstan, that they would understand and accept us here. They sent us to Pavlodar. But it’s cold there. What would we do there, in the north? Here we have all of our family. Our grandkids cannot go to school, even private schools don’t accept us. But I think everything will turn out fine,” Bekaly concluded with a smile.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.