Special European Union envoy on sanctions David O’Sullivan stopped in Kazakhstan on November 28 during a tour of countries that have not joined the West in sanctioning trade with Russia in an effort to harm its continued military offensive against Ukraine.

The EU, along with the US, the UK, and other G7 countries, imposed sanctions on goods, companies, and individuals in an effort to thwart Russia's military operation. A secondary, but crucial reason for sanctions, is to weaken Russia’s economy to the point that its war in Ukraine becomes too expensive to carry on.

O’Sullivan’s press conference was largely misunderstood by local and international media, which only focused on the partial decrease in re-exports.

“The purpose of these visits is not to persuade countries to adopt our sanctions or to align with them, but to discuss with them how they can avoid their jurisdiction being used as a platform for the circumvention of our sanctions or indeed as a platform for servicing the Russian military industrial complex,” O’Sullivan said.

At the same time, the EU envoy made clear that a continuation of re-exports from Kazakhstan could put a dent on mutual relations and hinder future investment.

“For countries such as Kazakhstan which wish to trade with the EU and wish to attract investment to acquire a name as a place where sanctions are evaded is not good for the reputation of the country or for the likelihood of people to want to invest and trade here,” O’Sullivan said, having clarified that this should not be considered a threat.

The EU, together with an international coalition of G7 countries, has drafted a list of 45 HS codes of products that could be used for Russia’s military effort against Ukraine. He noted that, since his visit in April, the export of some of these products has declined, while certain other products have been sold to Russia at a higher rate.

“More work needs to be done,” O’Sullivan noted.

When asked about how many (and which) companies have been circumventing sanctions, he failed to give concrete numbers.

"Of course there are companies doing that. The question is whether this is something which is done in full knowledge of the ultimate destination or not,” O’Sullivan quipped.

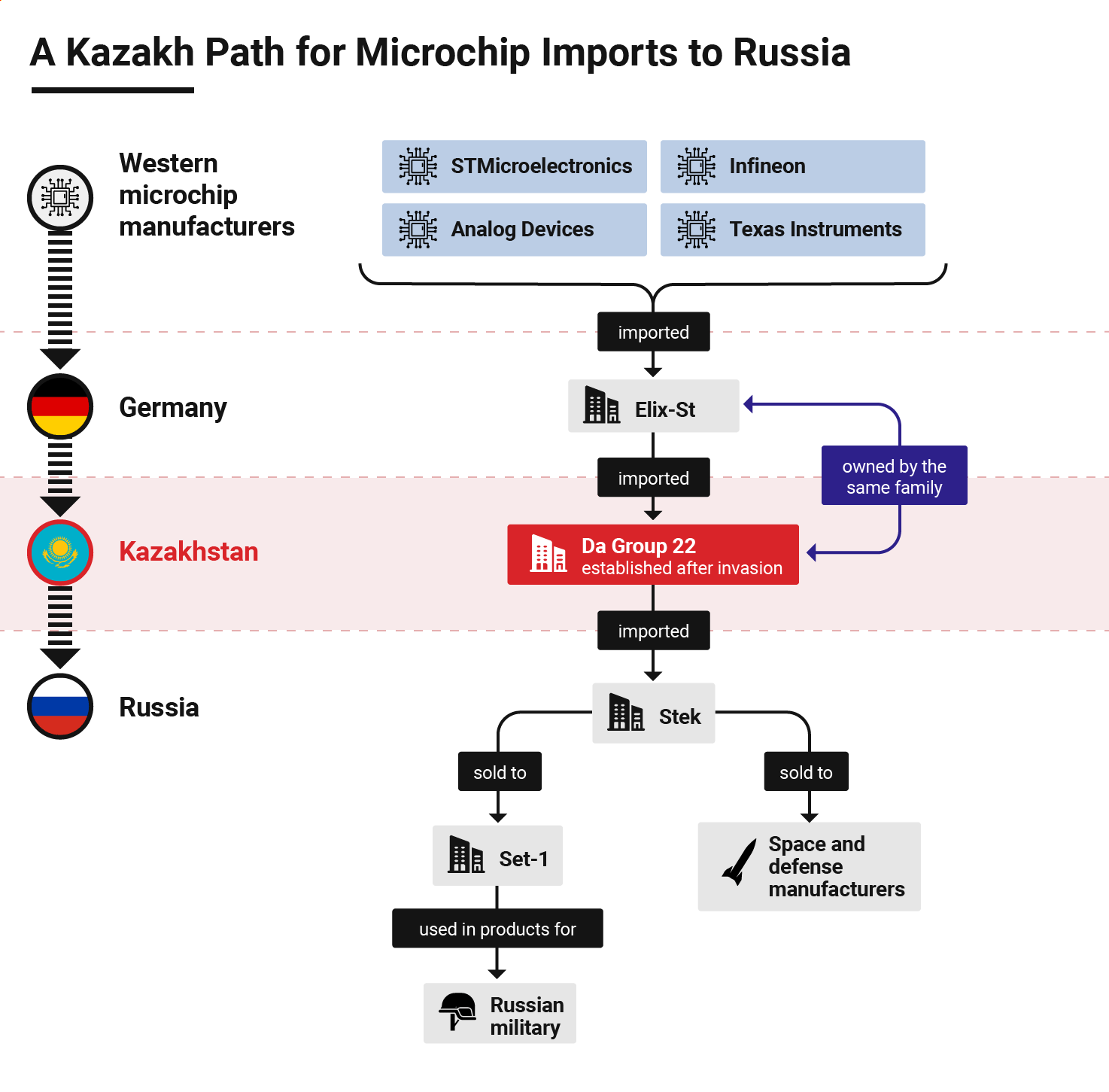

An infographic from an investigation by Vlast, OCCRP, iStories, and Der Spiegel published in May 2023.

Olzhas Kizatov, deputy head of the Agency for the Regulation of the Financial Market, confirmed in an interview with Vlast that the Agency does not have a list of companies in Kazakhstan that are helping circumvent the sanctions regime.

“The special envoy did not meet with us this time. The last time, he gave us a list of sanctioned goods, which is publicly available,” Kizatov said.

At the press briefing, O'Sullivan could not name any concrete steps by the government of Kazakhstan in their fight against sanctions circumvention.

“It would be best to ask the Kazakhstani authorities about what exact administrative mechanisms they are using,” O’Sullivan answered Vlast.

Sanctions Around the Corner

O’Sullivan’s words, while providing an optimistic outlook, were a call to action, because of the shortcomings in stopping trade of banned products to Russia. His remarks hinted at the possibility of punishing those companies that circumvent Western sanctions.

Chris Tooke, a director at the political risk consultancy JS Held, said Kazakhstan is aligning with the West, albeit in a constrained fashion.

“A fear of falling under secondary sanctions is an important factor, and the visits of foreign envoys have reinforced this fear,” Tooke told Vlast.

Besides O'Sullivan's visit in April, James O’Brien, head of the office of sanctions coordination at the US State Department and UK Minister with a portfolio on sanctions Nusrat Ghani also visited Kazakhstan in recent months.

“But we shouldn’t see this as just a response to Western pressure: it also reflects [President Kassym-Jomart] Tokayev’s balancing act between signaling tacit opposition to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.”

Zhanibek Arynov, assistant professor at Nazarbayev University, told Vlast that the EU envoy said nothing new, but perhaps reinforced the fear of secondary sanctions.

“I think it is unavoidable that some Kazakhstani companies will end up in the Western sanctions list,” Arynov said.

While Kazakhstan has shown good will in its responses to the EU’s requests, it is clear that halting parallel imports would impose a high cost on the country’s economy and would ultimately be difficult to implement, especially given Kazakhstan’s membership in the Eurasian Economic Union (together with Armenia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia).

Marcus How, head of analysis at VE Insight, a political consultancy, said that stopping the export of banned goods to Russia is ultimately a question of regulatory enforcement.

“On paper, the government has undertaken some important measures in 2023 to ensure compliance with Western sanctions on Russia. Yet the authorities will not – or cannot – take measures that would fully shut down parallel imports. There are two reasons for this: viability and costs,” How said.

Kizatov, at the regulatory agency, agreed. Kazakhstan’s banks, he said, must be careful but are still going to do business with Russia, one of Kazakhstan’s largest trading partners.

“Our banks have something to lose. They do not want to take unnecessary risks, but at the same time, they need to continue to finance trade between Kazakhstan and Russia,” Kizatov told Vlast.

“Because all major Russian banks are on the sanctions lists, our banks are now increasingly eager to open correspondent accounts in non-sanctioned medium and small Russian banks. This way, we comply with all sanction requirements,” Kizatov said.

Numbers Don’t Lie

At the press conference, O’Sullivan noted that the EU is the top trade partner of Kazakhstan, in another attempt to show the importance of the relationship. Once the numbers are broken down by country, however, the largest trading partner in the EU is Italy, with around $11.7 billion (mostly in imported oil) in the first three quarters of 2023. In the same period, China ($21.7 billion) and Russia ($19 billion) overshadow Kazakhstan’s western partners.

The statistics also show that Kazakhstan has been used as a conduit for parallel trade to Russia. Compared to the first nine months of 2022, this year’s imports from countries outside the Eurasian Economic Union have increased by 51.5%. At the same time, exports to Russia have jumped 12.3%, whereas exports to other countries have generally stagnated or declined on the back of weaker oil prices.

In short, the Kazakhstani vector for the sale of Western products to Russia has worked, and it has proved to be a lifeline to Kazakhstan’s economy at a time of diminishing returns from oil exports.

Robin Brooks, chief economist at the Institute of International Finance, who regularly highlights odd statistical trends in trade flows, showed how the chart of EU exports to Kazakhstan has changed significantly since Russia started its war on Ukraine.

Monthly exports from the Euro zone to Kazakhstan have doubled since Russia invaded Ukraine. Since Feb. '22, "excess" exports to Kazakhstan total EUR 7 bn, so the numbers aren't small. Only way to stop this is to lower the G7 cap. If Putin runs out of cash, he can't import... pic.twitter.com/6ZqYzoyLrL

— Robin Brooks (@RobinBrooksIIF) November 29, 2023

In the first months after February 2022, it became clear that trade flows would have to be redrawn, as some of the largest economies reshaped their diplomatic relations. Since the establishment of a sanctions regime against Russia, the EU is putting its efforts into ensuring that its companies abide by the new trade rules and that other countries do not become a platform for sanction circumvention.

“We are progressively making it harder, slower, and more expensive for Russia to acquire military-use equipment,” said O’Sullivan. Yet, the numbers and a range of investigations tell a different story.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.