- ВКонтакте

- РћРТвЂВВВВВВВВнокласснРСвЂВВВВВВВВРєРСвЂВВВВВВВВ

Kazakhstan’s oil history starts in the Caspian region, when oil gushed out of the Karashungyl field in 1899, under the Russian Tsarist rule. The following years drove Russian and Western engineers to establish production companies and ventures in the Emba region, until the Bolshevik revolution led to a nationalization of the oil fields.

This is, in brief, the first chapter of Kazakhstan’s oil history. In a continued effort to build the country’s identity around his figure, former President Nursultan Nazarbayev, wrote a 700-page autobiography in which he also talks about the country’s oil industry, not without mistakes and omissions.

Nazarbayev notes that Alfred Nobel, of the oil business family known as the Nobel Brothers, was among the first oilmen to visit Kazakhstan.

“Yes, don’t be surprised, the man behind the prize started his business career in our steppe,” Nazarbayev argues.

He is wrong by about 25 years and a few hundred kilometers.

In fact, the Nobel Brothers had famously exploited the nascent oil business in Azerbaijan, producing oil in the Absheron peninsula in the 1870s, and built a pipeline across the South Caucasus to Georgia, all before the oil fountain spurted at Karashungyl.

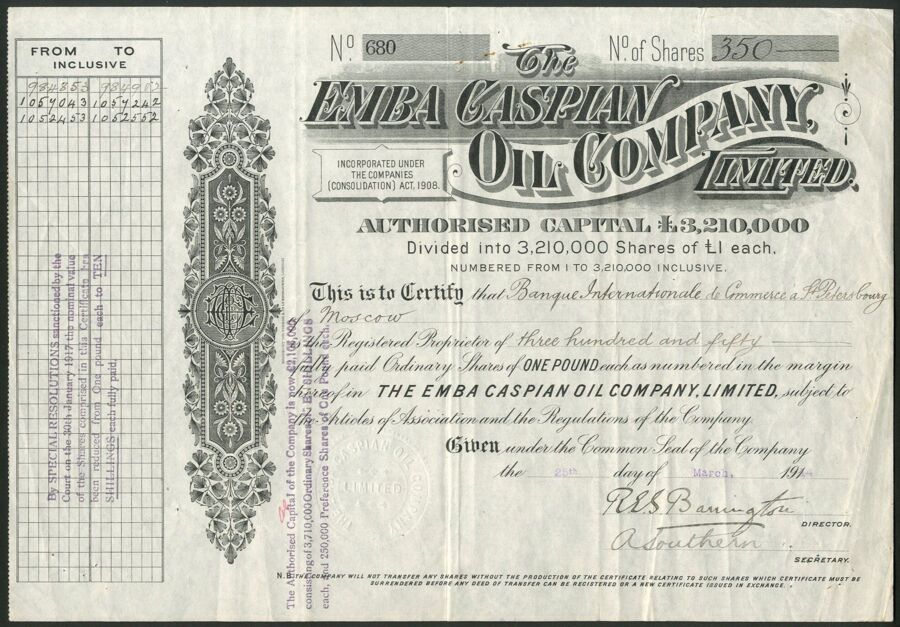

Nazarbayev then skips over what could be defined as a “looting” of Kazakhstan’s oil industry in the first two decades of the Twentieth Century, with foreign companies leveraging their expertise to produce and sell Kazakhstan’s oil. When the Emba Oil Company was founded in 1912, its shares were listed on the London Stock Exchange in an effort to boost production.

Instead of focusing on this period, during which hundreds of workers were killed or injured in the process of building a pipeline connecting the Emba oil fields to the Volga region, Nazarbayev accuses the Soviet regime of taking ownership away from the people of Kazakhstan.

“Although such riches were found in its subsoil, Kazakhstan could not own them. The entire oil industry was led by the Union ministries. The top leadership of the USSR did not give us the opportunity to develop and produce hydrocarbon raw materials by ourselves and were jealous of all our initiatives.”

Against Gorbachev

In his 2008 book Space, Oil and Capital, scholar Mazen Labban argued that then-Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev opened the door to foreign capital investment into the Union’s oil and gas sector.

This was also true in Kazakhstan’s case, as Gorbachev and his ministers made plans with US company Chevron to help Soviet enterprises develop the giant Tengiz oil field, discovered in 1979. In the 1980s, Chevron beat the competition of other foreign companies in a process that excluded the participation of the local government of the Kazakh SSR, according to another book, The Black Blood of Kazakhstan, by journalist Oleg Chervinskii, published in 2017.

Nazarbayev confirms that he, as the industrial secretary of the Central Committee, as well as Politburo member “[Dinmukhamed] Kunayev were not in the loop about the Soviet-American negotiations over Tengiz. And the information about the reserves at Tengiz became a state secret, kept under lock and seal”.

The former president then goes on to argue that he was the architect of a sort of re-nationalization of the oil industry already before the fall of the Soviet Union.

“In July 1991, I wrote a letter to Gorbachev [which said] that ‘from this moment on, Kazakhstan takes control of the field’.”

At the time, Nazarbayev had started his own negotiations with Chevron.

And yet, according to Chervinskii, the local specialists had already been involved in the negotiation process already in June 1990, with Kazakh SSR officials being involved in September 1990.

After independence, Kazakhstan’s oil industry represented the main attraction for foreign investors. As Chervinskii writes, with reference to the early months of 1992: “At the airports of Almaty and Atyrau, planes approaching outside the regular schedule land with only few people on board, all carrying bundles of dollars.”

These envoys were sent by international oil and gas companies to set up their new headquarters in the countries.

Selling Out

The much-criticized “secret negotiations” during Soviet times did not become more transparent under Nazarbayev. The landmark agreement between the government of independent Kazakhstan and Chevron from April 1993, in fact, has never been public.

In “My Life”, Nazarbayev contends that he improved the conditions of the contract that Gorbachev had signed with Chevron.

“We reduced the land plot assigned for oil production from 23,000 square kilometers to 2,000 square kilometers, we reduced the length of the agreement from 50 to 40 years, and we [obtained] that the American side only received 19% of the revenues, and not 29% as they wished.”

According to Nazarbayev, under these conditions (the land plot was later increased to 4,000 square kilometers), the government agreed to sign the joint venture contract that established Tengizchevroil, which remains to date the country’s largest taxpayer.

The share of revenues was - allegedly - ultimately set in a 80:20 split in favor of Kazakhstan’s government. But Kazakhstan’s public has little clue of what went on behind closed doors since the signing of the so-called “deal of the century”.

Kazakhstan’s government quickly sold off part of its 50% stake in Tengizchevroil to Mobil (now ExxonMobil, which bought a 25% stake from the government for $1 billion), and Russia’s Lukoil (which purchased 5%, leaving Kazakhstan’s stake at 20%).

In 2002, then-prime minister Imangali Tasmagambetov candidly admitted that the deal to sell the shares to Mobil entailed the creation of secret Swiss bank accounts, which could only be accessed by Nazarbayev, ex-oil minister Nurlan Balgimbayev, and former prime minister Akezhan Kazhegeldin. This was just one of the bank accounts that US and Belgian prosecutors found, ironically, after Kazakhstan’s government requested an investigation on Kazhegeldin’s foreign holdings, once he became a sworn enemy of Nazarbayev’s.

My Life, My Country

The Tengiz deal was brokered by James Giffen, an infamous middleman from California, who obtained a per-barrel royalty from the deal (he became known as Mr Seven-and-a-Half-Cents), making hundreds of millions of dollars over three decades. Giffen was also instrumental in helping Nazarbayev set up a bank account in Switzerland, used to funnel opaque funds, in a scheme that hit the headlines as “the largest foreign bribery cases in US history.”

The case, known as “Kazakhgate”, was described by the New York Times in 2006 as “a labyrinthine trail of international financial transfers, suspected money laundering and a dizzying array of domestic and overseas shell corporations”. At the time, Giffen was facing trial for channeling more than $78 million in bribes to Nazarbayev and the head of the oil ministry, Nurlan Balgimbayev. The US attorney named Nazarbayev “an unindicted co-conspirator”.

In 2010, however, Giffen left a US courthouse a free man after paying a mere $20 fine (yes, twenty US dollars). He had claimed to have acted on behalf of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), when in the 1990s the CIA aimed to gain political and diplomatic influence in Kazakhstan.

Besides the well-documented cases of corruption, in the “oil” chapter of his latest memoir, Nazarbayev also glossed over the worsening conditions of the industry’s workers, the abysmal industrial and environmental conditions, and the common offshoring practices that his regime first facilitated and then formally condemned.

Nazarbayev repeatedly accuses the Soviet leadership of taking Kazakhstan’s oil resources away from the people. Yet, the former president fails to finally admit that, when he got to power, he too was the protagonist of a personal, large-scale, secret, and opaque extraction of oil wealth from the public.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.