Since the Crocus City Hall attack on March 22, the Russian government has acted through immigration and legislation, in an attempt to curb the arrival of Central Asians and to enforce their deportation.

In the months following the attack, the Kyrgyz, Tajik, and Uzbek governments have advised their citizens against traveling to Russia. The Russian government has also set up new bilateral migration rules with Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan in an effort to outsource tougher screening procedures to the country of origin.

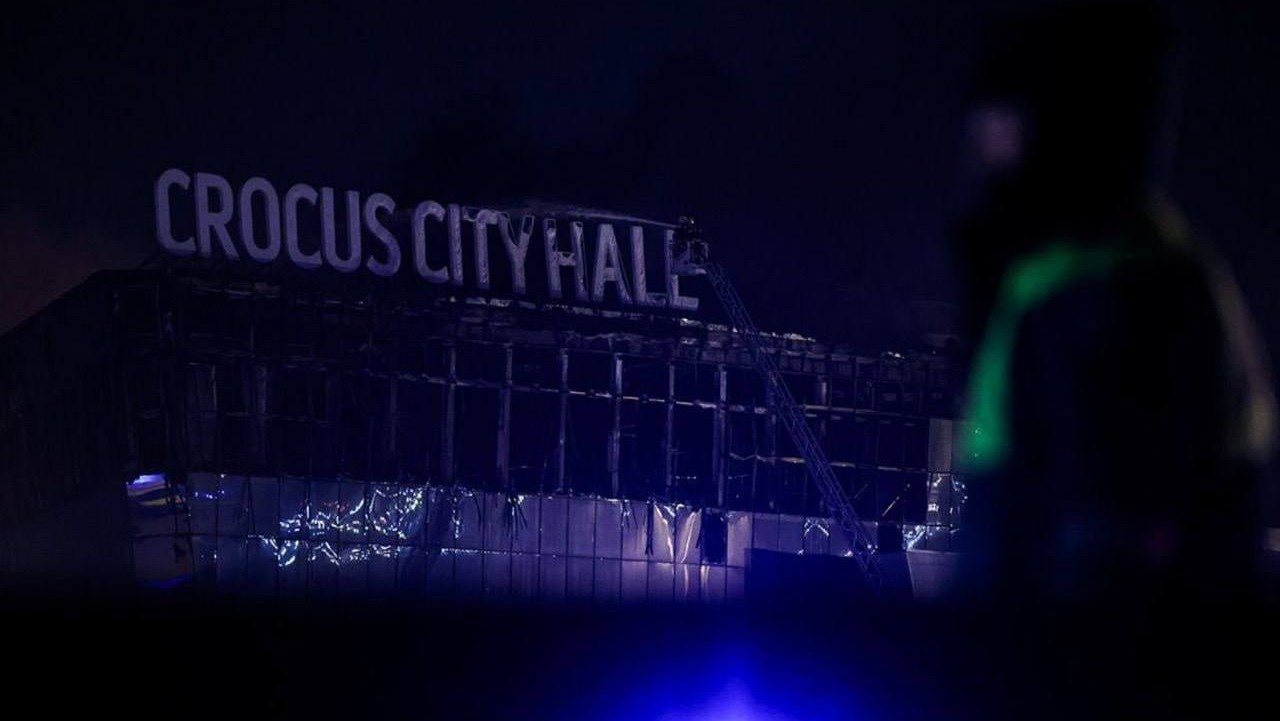

The Crocus Attack

On March 22, gunmen entered the Crocus City Concert Hall in Krasnogorsk, just outside of Moscow, and opened fire onto the public in and outside of the venue, before setting it ablaze.

In what was the deadliest attack in Russia in over 20 years, 145 people were killed and over 500 were left injured.

The Islamic State - Khorasan Province (ISIS-K) claimed responsibility for the attack after four gunmen identified as Tajik citizens were taken into custody. Initial claims from Russian authorities linked the attack to Ukraine, the United States, and other western countries.

This was the first ISIS-K attack outside of South and Central Asia.

Since the attack, instances of xenophobia, assault, and harassment towards Central Asians in Russia have been on the rise, regarded by many as ‘petty’ acts of ‘collective punishment.’

According to Nodira Abdulloeva, an advocate for the rights of migrant workers in Russia, the harassment against Central Asian migrants has deep roots.

“The racialization of Central Asians had already picked up during the COVID-19 pandemic and especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But since the Crocus attack, the number and intensity of harassment and attacks have reached an unimaginable level,” Abdulloeva told Vlast.

Pen in Paper

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin signed a fresh set of amendments on border crossing and migration into law on August 8, which will take effect on 1 January 2025. Many human rights activists claim these amendments specifically target and restrict the rights of non-Slavic migrants.

Vyacheslav Volodin, the chairman of the Duma, the lower house of parliament, made it clear that “those who do not comply with Russian laws, who have lost the right to legal residence in Russia, should not be in our country.”

Migrants can land themselves in the expulsion regime for offenses that include disobeying a police officer, petty hooliganism, and providing false migration information.

The amendments state that those in the expulsion regime will be prohibited from traveling outside their residence, driving a vehicle or obtaining a driver’s license, conducting any banking activities outside of mandatory operations, or getting married, among other restrictions.

According to Valentina Chupik, a Russian pro-bono migration lawyer, the new rules will allow the police to fully control and monitor the lives of labor migrants, restricting their everyday actions once they fall in the expulsion regime.

To obtain a work permit, migrants are required to acquire a certificate demonstrating their knowledge of the Russian language, history, and laws. If the police determine that a migrant’s certificate is invalid, then they may be subject to the expulsion regime and deportation.

The migration process is by no means easy, particularly from an administrative perspective. According to Syinat Sultanalieva, a Central Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch, the legislative ambiguity around legal migration is a big worry for many who try to make a move further north for work.

“It’s almost impossible to be legal. Migrants know how problematic it is to illegally stay in Russia, but the system is so complicated. Then, when they do get caught by the police, that’s when the problems start,” Sultanalieva told Vlast.

Taking Matters Into Their Own Hands

Reports in Russia of ethnic Central Asians being harassed, detained, deported and their homes raided have gone rampant since the Crocus attack.

Central Asians have been detained at border crossings without reason and held in detention centers for days on end in inhumane conditions. Many have just been told to turn around and not come back, even though they possessed all the proper documents.

There are already existing cases of Russian police tracking the location of migrants and storing their biometrics. Police are deceiving migrants about their immigration status, falsifying migration offenses, and are now legally allowed to detain anyone and prosecute them without any proven violation or offense.

Central Asian migrants often have to pay bribes to be released from the police, amounting to an average of $150 per bribe, according to a source of The Moscow Times.

According to Noah Tucker, an associate at the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard University, Russian laws only go so far.

“Very rarely has the law prevented a police officer or military recruiting officer in Russia from doing whatever they wanted to Central Asians at that moment,” Tucker explained to Vlast.

Local government leaders have begun banning Central Asians from working certain jobs they previously held. In Yakutia, migrants have been banned by the local government from driving taxis or other public transportation vehicles.

Russian citizens have also made life increasingly challenging for migrants, according to Edward Lemon, Assistant Professor at The Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University.

“In the days following the attack, [Central Asian-owned] businesses were firebombed and there were dozens of cases of ethnically motivated violence. Tajiks have reported being evicted without reason. Screenshots have circulated on social media showing taxi riders on apps like Yandex refusing to ride with Tajik drivers. Viral videos are circulating social media calling on Tajiks to be deported, claiming they are all ‘terrorists’ and calling for the death penalty to be reintroduced,” Lemon told Vlast.

A Murky Future

“People have gotten the message. Central Asians don’t feel welcome or safe in Russia right now, and a lot of migrants are saying they’re going to migrate somewhere else,” Tucker told Vlast.

The Russian labor shortage reached 4.8 million workers at the end of 2023, primarily due to the country’s war efforts in Ukraine. With the adoption of the new amendments, that number could increase further.

However, given Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan’s heavy reliance on remittances from Russia, Tucker remains concerned about the feasibility for Central Asians to work elsewhere.

“Next spring, most of these migrants will have to go back to Russia again, and Russia might use these tools to force them to accept conscription to fight in Ukraine,” Tucker told Vlast.

Multiple reports have indicated that Central Asian migrants have been enticed to join Russia’s war efforts in Ukraine, either forcibly or in exchange for state benefits, including Russian citizenship.

Andrew Gundal is a contributing writer on Central Asian affairs.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.