From the time it opened in 1964, up until the collapse of the Soviet Union, Tselinny worked for 27 successful years. This piece delves into the cinema’s golden era.

To go back to the time when Tselinny was first planned and built, read this piece.

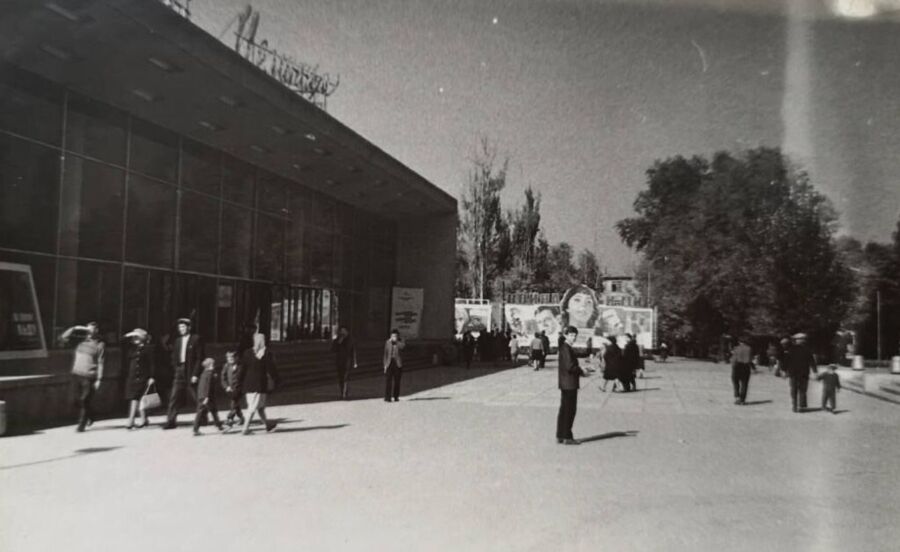

By the end of 1966, there were 19 movie theaters in Almaty, 10 of which had permanent shows. Eight million viewers sat on their chairs that year. Tselinny was the largest of the landmark theaters, serving as both an entertainment hub and an educational platform.

Tselinny’s commitment to education extended beyond its screens. School teachers were part of Tselinny’s own committee for children's education, which gave recommendations on which movies to show.

Senior school students could join a film club, during which viewers could meet with actors and directors, and watch Soviet and foreign classics. The documentaries that Tselinny carried spanned from air defense to a critique of religion as “opium of the people.”

Tselinny, as well as the other landmark cinemas, like Alatau and Sary-Arka, hosted a range of exhibitions: Asian, African, and Latin American film festivals, or the Week of Czechoslovakian films, or the Festival of Yugoslav and Ukrainian films.

Before IMAX

In the late 1970s, Tselinny switched from the panoramic to the wide format. The industry churned out fewer and fewer panoramic films, which were more costly and complex.

The panoramic technology used split images, each filmed with its own lens on a separate film. Muslim Chinguzhinov, a veteran in film distribution, says that the panoramic format is essentially the ancestor of today's IMAX.

“Three projectors worked at once beaming the images into a massive canvas. It was a huge spectacle. When Tselinny was panoramic, the screen was about 30 meters wide and about 8 meters high. At the beginning of the 1970s, the theater turned to a wide screen format, and the canvas was slightly reduced,” Chinguzhinov told Vlast.

“When a panoramic film about motorcycle races came out, the stereo sound effect moved around the perimeter of the hall as the motorcycles moved, it was as if the motorcycles were driving around the hall.”

According to Chinguzhinov, Tselinny featured unique barn door devices. This fabric, stretched over a frame to remove excess screen space, was used to eliminate the white stripes along the edges, something that gave the viewer the impression that they were watching a full screen, whichever the format.

Bella Akhmadullina in Tselinny

In the winter of 1980, Tselinny hosted a performance by Bella Akhmadullina, a renowned poetess. She had been at the center of a scandal two years prior, when Metropol, an independent publication (samizdat) featured uncensored works by a number of writers, including Akhmadullina.

Then a journalism student at the Kazakh National University, Olga Gumirova heard that Akhmadullina was coming to Almaty.

"Akhmadullina's visit was not covered much because she arrived after the release of Metropol. She performed several times here. Tselinny featured some of the most controversial shows," Gumirova, who went on to become a famous journalist, told Vlast.

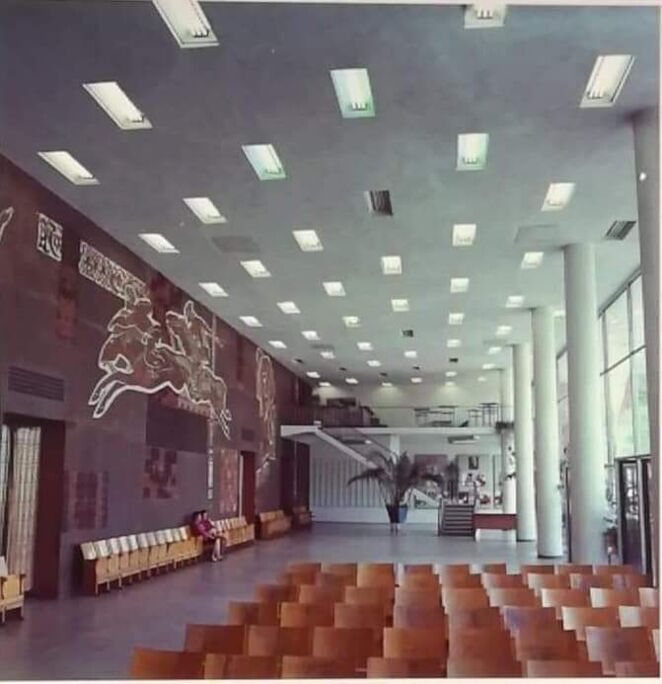

During one of these shows, someone gave Akhmadullina a note from her many fans who could not get tickets to her performance. The poetess asked to let everyone into the hall, which quickly became packed with the audience standing by the walls and sitting amid aisles.

“The huge number of people contrasted with the absolute silence there was when she read her poetry. We were sitting very close to the stage, and I remember her porcelain white neck, which stretched forward, like a bird, when she recited. She was wearing a white lace blouse, her hands donning rings so beautiful, we had never seen,” Gumirova said.

“Akhmadulina looked like the personification of poetry. She evoked absolute admiration, it was a pleasure to listen to every word. How did all those people know Akhmadullina? Most likely, from some underground reprints, because her books could not reach our city.”

A Test for Technicians

Tselinny also functioned as a training ground for projectionists who needed to be certified. Given how little they were paid, most projectionists were young people, which caused a fast-paced turnover. As soon as they mastered the profession, they had become of age to serve in the army. In the minutes of a meeting retrieved from the city archive, cinema directors discuss problems in this workflow and propose giving employees free accommodation to motivate them to stay on.

After receiving his certificate in Tselinny, Chinguzhinov started working as a projectionist at the Yunost cinema in 1984-1985. He would then continue at the Avangard and Kazakhstan cinemas. Chinguzhinov recalled the special technical room, equipped with everything, from narrow-film projectors to stationary 70-millimeter ones.

To make it into the first of three tiers of the trade, aspiring projectionists like Chinguzhinov went to a technical school and studied film for four years, specializing in "maintenance and operation of film equipment and design of cinema halls."

Chinguzhinov remembered that the best projectionists had worked in Tselinny’s technical office since 1978. They always wore blue robes in the cinema, their sleeves always buttoned up. They could not wear long hair for safety reasons.

“God forbid the film broke or there was a stoppage and it was the technician’s fault. At that time people were punished for this, they were deprived of bonuses, and sometimes demotes,” Chinguzhinov told Vlast.

Socialist Competitions

Like other enterprises in the Soviet Union, cinemas held “socialist competitions” among themselves. In 1965, such a competition started between Alatau and Tselinny.

The theaters committed to fulfilling the plan for cinema services ahead of schedule, outpacing each other in their educational-ideological role, and implementing the decisions of the Communist Party’s central committee.

In addition, the employees promised to bring down energy and operating costs. According to archival documents, “Team Tselinny” actively took part in this socialist duel in 1965-1966. There is no record of the ultimate “winner.”

During this time, cinemas introduced innovations. They now featured new box offices for advance ticket sales and offered the possibility to buy tickets on credit for a period of one month. Twelve billboards around the city near Tselinny announced new movie shows. On Sundays, unlike the typical Soviet tradition of “subbotnik,” cinema employees went out to paint trash cans or benches, and restore flower beds around the building.

In 1966, Tselinny’s management committed to major renovations ahead of the 50th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution and the 100th anniversary of Lenin's birth. The cinema managed to exceed the plan every month, "satisfying the viewers’ spiritual and aesthetic needs and improving the culture of service to the people."

Judging by the box office receipts in 1970, Alatau was more efficient than Tselinny. The former held 2,987 screenings, 306 more than Tselinny. Yet, the latter’s much larger hall, allowed Tselinny to attract more viewers. Panoramic format shows at Tselinny garnered 905,000 roubles. Both cinemas exceeded the state plan.

In 1970, the local Communist Party awarded Tselinny with an honorary diploma. Tselinny was now officially recognized as the best cinema in the Republic.

"What Kind of Jungle Have You Created Here?"

Maira Kubaniyazova worked as an emcee at Tselinny from 1981 to 1986. She set up film festivals and theme nights.

“I organized everything, invited people, wrote the scripts, and went on stage. We had events for New Year’s, Soviet Army Day in February, the Eighth of March, Cinema Day, May Day, and so on, all year long,” Kubaniyazova recalled.

She had studied to become a teacher, but then got a job at Tselinny by chance:

"The cinema was beautiful and large. The foyer was small and cozy, with lots of plants. I remember palm trees,” Kubaniyazova told Vlast.

“There, I met a woman who worked as a ticket inspector, but doubled as a gardener as well. And she loved it. One day, a film official came to Tselinny and was indignant: ‘What kind of jungle have you created here?’ We had to remove half the plants."

Back then, cinema was the only entertainment available. When a good film came out, especially a foreign one, you had to buy tickets in advance. On weekends, Tselinny was packed already from early morning.

Because she worked in “the country's most important movie theater,” Kubaniyazova was constantly asked to get tickets. Viewers even offered bribes: They would try to pay three or five roubles for a ticket that cost 50-70 kopecks.

The films were shown for about two weeks, but if a certain movie proved popular, the screening could be extended for a month. This created competition among cinemas: Since Tselinny, Alatau, and Sary-Arka got the premieres, the others had to wait until their showings finished before they could get their hands on the reels.

Cinemas were part of the Soviet Union’s planned economy. If a theater met the goals set in the central plan, the employees were given a bonus.

Kubaniyazova recalls that they collaborated with other state-owned enterprises to attract viewers. Large factories would feature mobile box offices and a “cinema corner,” where new movies would be advertised. Each ticket inspector at Tselinny had their own enterprise to woo. Kubaniyazova’s prior experience took her to schools and education institutes.

"We gave schoolchildren subscriptions. They were a booklet of tickets that would be torn off at each visit. Through this, we had guaranteed viewers, which contributed to the fulfillment of the plan. We called universities and enterprises, went there to tell about movies coming out soon. This is how we got our bonus."

The advertising near the cinema was produced locally. Tselinny had two artists on staff, a designer for the poster and a typographer for the fonts. In total, in the 1980s, Tselinny employed about 60-70 people.

"From the outside, it might seem that you only need a cashier, an inspector, and a technician. But you also need cleaners, an electrician, and many other figures," Kubaniyazova said.

In 1986, Almaty hosted for a second time the All-Union Film Festival, prompting the renovation of Alatau, Tselinny, Sary-Arka and Arman. were renovated.

This centralized film distribution system collapsed with the fall of the Soviet Union. What ensued were hard times for movie theaters. In this piece, we tell how Tselinny survived the 1990s.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.