After years of campaigning for a transition away from coal-powered electricity and heat, in December 2023 Kazakhstan’s government surprised everyone and awarded Russian firms fresh contracts for the construction of new coal-fired power plants totaling 4.6 GW.

The decision came just 10 months after the adoption of a Strategy for Achieving Carbon Neutrality by 2060. According to Climate Action Tracker, Kazakhstan has “the world’s 16th highest per capita and fourth highest per GDP emissions,” and is implementing “insufficient” policies to reduce emissions.

Осы мақаланың қазақша нұсқасын оқыңыз.

Читайте этот материал на русском.

Air pollution continues to severely affect the country’s largest cities, with former capital Almaty regularly making headlines as one of the world’s most polluted.

This disconnect between government rhetoric and actual policy is obscured by frequent announcements of new renewable energy projects, often in cooperation with extractive companies or large development institutions.

Our deep-dive into the renewable energy sector reveals that Kazakhstan’s transition to renewables is hampered by three powerful forces: the coal lobby, government inertia, and oil and gas companies.

Kazakhstan’s Green Ambitions: Too Little?

For an oil-exporting country like Kazakhstan, focusing on renewable energy sources could seem counterintuitive. After all, most hard currency revenues from exports come from the hydrocarbons sector.

“I personally do not believe in alternative energy sources, such as wind and solar,” said then-President Nursultan Nazarbayev in September 2014.

Cheap, available oil and coal have fueled Kazakhstan’s economy for decades, and the latest decarbonization strategy appears to shift policy in the opposite direction. This had most of the government cheering on the policy shift.

According to Nikos Mantzaris, senior policy analyst at The Green Tank, Kazakhstan’s goals could reach deeper than just aiming for carbon neutrality in a couple of decades.

“Talking about carbon neutrality by 2060 is not very ambitious if you're only talking about power generation. They might present this as ambitious, but I don't consider it amazing. By 2050 in Europe we will be carbon neutral accounting for all energy,” Mantzaris told Vlast.

One of the main questions regarding the 2060 Strategy is that it talks about “alternative sources of energy,” not directly about renewables. This could include nuclear energy, something that is not widely considered as having the same decarbonizing effects as wind or solar and entails risks of failure, exposure to radiation, and waste storage that detractors of the prospective nuclear power plant have voiced in the past.

The government’s language, in this sense, is unequivocal.

“The development of nuclear energy is an integral part of the plan to reduce the carbon footprint,” Almasadam Satkaliyev, the former minister of energy, said earlier this year.

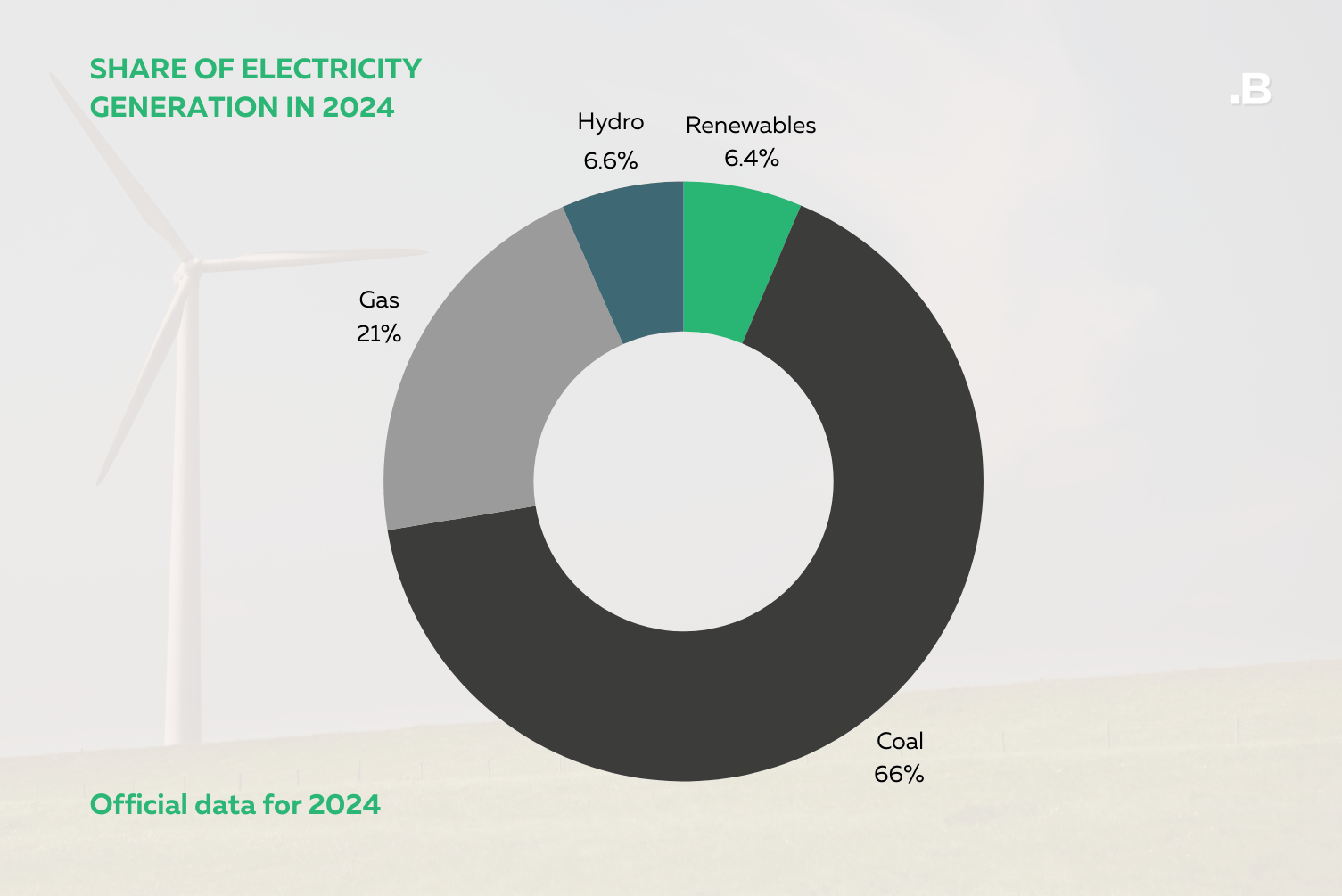

“By 2030 the volume of electricity produced with renewable energy sources should be around 30%. Today it is [a little less than] 7%. Therefore, new alternative energy sources will be introduced,” Yerlan Nysanbayev, the minister of ecology told Vlast.

Jean-Pierre Callens, a senior consultant in renewable energy projects based in Astana, told Vlast in an interview that Kazakhstan’s potential in terms of wind and solar power could turn it into a regional leader.

“Kazakhstan has huge resources, plenty of sunshine, plenty of wind. This country could easily become the number one supplier of energy for the whole Central Asia region if it bets seriously on renewable sources. That needs a long-term government vision for the next 20–30 years and, crucially, incentives,” Callens told Vlast.

As argued in a 2024 analysis, “Kazakhstan could have the potential to increase the share of clean wind and solar electricity sources at least fourfold to 20% by 2030, above the current target of 15%, reducing coal dependence and increasing the reliability of the grid and building an independent power generation sector.”

But what is hampering a long-term vision on renewables? Our investigation found three currents pulling in different directions: The coal lobby, ministries and government agencies, and oil and gas companies.

The coal lobby has, for decades, kept a stronghold on the energy industry in terms of both electricity and heat generation, in concert with the distribution lobby and the highest echelons of the government.

At the same time, the government, between ministries and agencies, has turned to renewable energy projects as a way to recycle its own investment and artificially allocate resources, no matter whether these projects are useful or effective, or even if they are eventually connected to the grid; this strategy ultimately creates rent-seeking projects to the benefit of government institutions and businessmen close to them.

Oil and gas companies, on their part, have used a number of investments into renewable energy projects to either power their own extractive industrial bases or to “greenwash” their reputation.

The three problems we describe are ultimately part of a bigger issue: the enduring absence of clean options on the agenda to power Kazakhstan. Citizens are unable to choose fairly among the market players, they cannot make a choice between cheaper or less polluting options, or options that would satisfy both their wallet and their need for clean air.

The Coal (and Gas) Lobby

The government has bowed to the coal lobby, spending billions in the renovation of coal infrastructure leading to limited benefits for the people and massive windfall for coal companies.

At the same time, the government has been slow in building a natural gas distribution network in the northern regions of the country, a move that gas industry lobbyists argue could be the gateway to a cleaner energy mix.

Now, the government’s plan to build new coal power plants (with the controversial help of Russian companies) has been tied to a prospective reconversion of these same plants into gas plants in the future, thus potentially more than doubling the cost of energy infrastructure that still fails to truly make Kazakhstan’s production greener.

“The prospective coal-fired power plants are considered a temporary measure to cover the electricity deficit until [other] large facilities are launched. All three new stations may be converted to gas in the future,” Satkaliyev told Vlast.

Experts argue that this plan is economically unsound, leading to excessive costs and delays in the transition to cleaner energy.

“Building new coal power plants now with the idea to readapt them into gas in a few years doesn't make any sense to me. When you build a power plant, it's not for six months, it's for 50 years. It's a complete waste of money,” Callens told Vlast.

The plan will entail a waste of both money and time, given that it would essentially postpone the decarbonization of the energy mix. Given the significant and constant fall in costs for installing renewable energy capacity, investing in new coal or gas plants would be economically counterproductive.

“It's complete nonsense from an engineering and financial perspective,” Callens told Vlast.

The Government Recycling Money

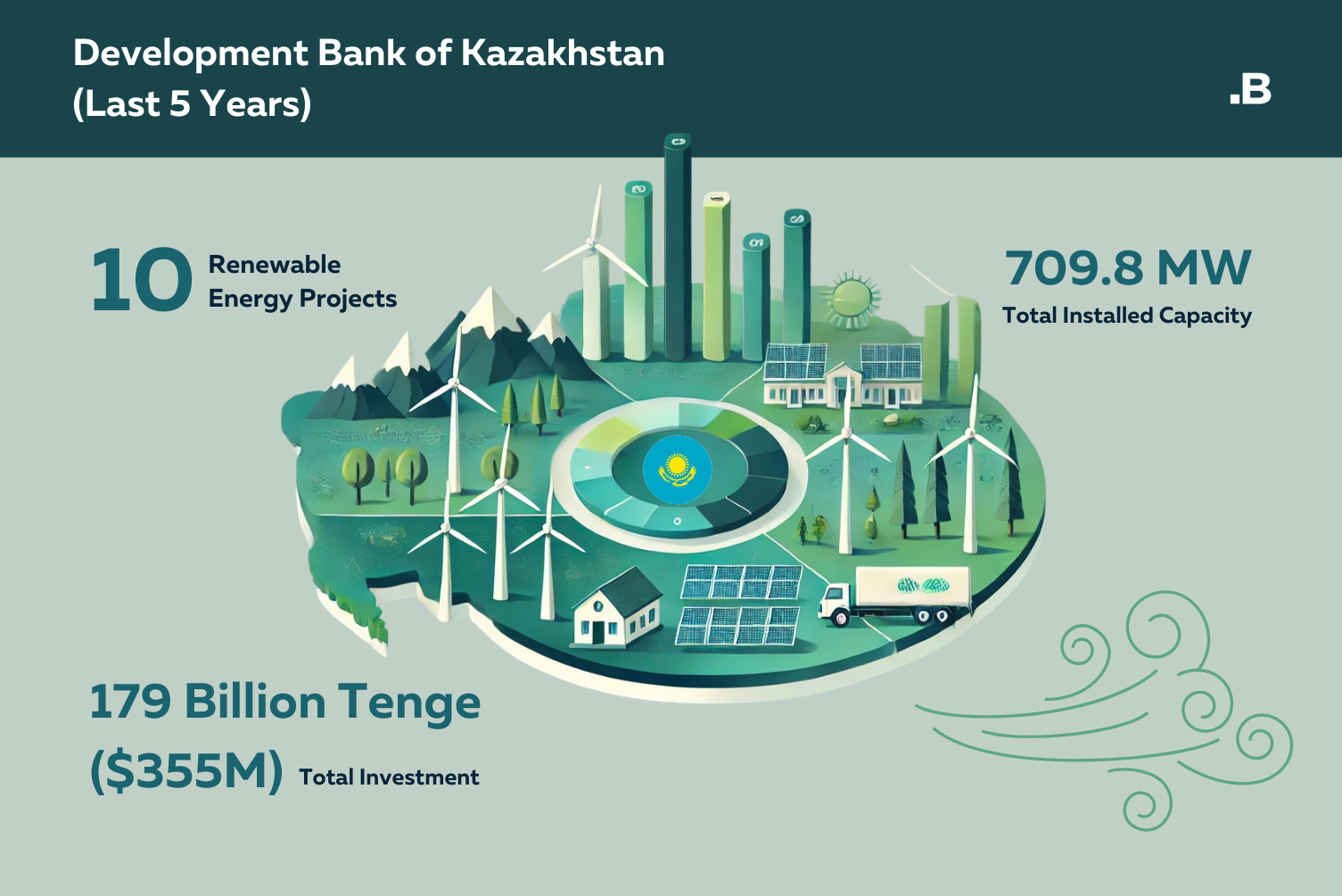

In the past five years, the Development Bank of Kazakhstan financed 10 renewable energy investment projects, with a total installed capacity of 709,8 MW. The total investment amounted to 179 billion tenge ($355 million).

Vlast reached out to an industry insider, who said on condition of anonymity that it would be difficult to develop a lively private sector in the renewable energy sphere because of low prices.

“Basically all wind projects in Kazakhstan are state-backed,” the source said.

Economist and former manager at the state-owned electricity distributor KEGOC, Asset Nauryzbayev told Vlast that for consumers, at the moment, nothing is cheaper than electricity produced from renewable energy sources.

“Renewable energy simply wins in price over any traditional source. And no government support is needed anymore,” Nauryzbayev said.

But agreements between companies and the government are opaque, according to Nauryzbayev.

“Tariffs for renewable energy are low right now in the market. But we only have one case of electricity being sold at market price. Everyone else signs agreements for twice as much. Instead of 2 cents, the government-owned utilities buy it for 5 cents. This is economic hardcore porn,” Nauryzbayev said.

Economist Almas Chukin, who also has direct experience in private renewable energy projects, agrees.

“Market players were forced out by the state. Only at first, the mechanisms of the renewable energy market were effective. The auctions were regular, open and transparent,” Chukin told Vlast in an interview.

“Then foreign giants flocked in to participate in the auctions and work without any local partners. Plus now there have been several government-to-government deals,” which have undercut private local producers, according to Chukin.

One example of government-to-government deals include the agreement Kazakhstan signed with UAE’s Masdar for a 1 GW wind farm.

“There, the process is built backwards: first they sign the agreement, and then they discuss the technical part and the price,” Chukin said.

According to Nauryzbayev, the government’s approach should be reversed.

“Rather than having a single developmental model for the energy sector, government agencies are guided by the president’s instructions and work with the figures he gives them. These agencies then go to private companies and ask them to build models that fit the requirements on paper,” Nauryzbayev said, adding that this is not how the process looks in other countries.

The reason that the final numbers are more important than the economics of renewable projects lies in the fact that the government uses investments into renewable projects as a way to inject cheap money into the economy.

“Companies receive low interest cash from the Development Bank of Kazakhstan, which gets it directly from the ministry of finance. The money stays in tenge, which means it’s not at risk of devaluation or inflation. Once the electricity is sold to state-owned companies at high tariffs and then to consumers, the money essentially returns to the state in the form of profits and taxes,” the industry insider said.

Experts agree that this upside-down process is only useful to balance the budget, not to foster decarbonization.

“Samruk-Kazyna is interested in the total number of wind power plants, not in their quality or their timely delivery. It just needs to accelerate the pouring of capital. Whether the plant will work or not is irrelevant. The more they invest into such projects, the more they earn.”

Greenwashing as a Corporate Strategy

Some of the largest industrial complexes in Kazakhstan are energy-thirsty and need continuous supplies of energy. Companies involved in fossil fuel extraction and steel-making, among other industries, consume around half of the electricity the country produces.

In an effort to slash the cost of fueling their operations, some of these industrial giants have embarked on investments in renewable energy projects tied to their own production base.

“[British oil company] Shell or Eurasian Resources Group build wind farms for themselves. If they install 200 MW, they know for sure that they will be able to consume it. ERG is building a facility in Khromtau, and all of it will go to the Khromtau Mining and Processing Plant, they will not care about the tariff set for this electricity. They will simply include the cost of electricity for their furnaces in the cost of the export contract for chrome. Therefore, they will always be in profit.” the industry insider told Vlast.

Companies profit from an energy strategy tailored to their needs, according to Nauryzbayev.

“Traditional electricity producers are all inside the Coal Energy Association. Kazakhstan’s energy strategy was written as a business plan for these companies,” Nauryzbayev said.

Despite a marked focus on traditional electricity production, micro grids have been used alongside industrial projects.

“Smaller pools of solar and/or wind power plants are an obvious solution for large manufacturing companies,” Nauryzbayev said.

Without state intervention, however, these would not be connected to the grid, thus contributing to meeting the domestic demand.

One solution would be to build a large number of smaller wind and solar projects.

“There should be 50 projects with an average operational capacity of 35 MW. For wind, for example, this means that installed capacity at each project should be around 110 MW,” Nauryzbayev said.

The goal, according to Nauryzbayev, should be to disseminate these projects across the country to prevent and address risks of gaps in electricity generation.

Bottlenecks and Solutions

Despite progress in the renewable energy market, bottlenecks still stifle the development of a competitive environment.

One of the main drawbacks of the current market for renewables in Kazakhstan is the overly fragmented distribution network, according to Nauryzbayev.

“Our market is very segmented. We have more than 50 electricity producers, but they do not compete with each other. They negotiate their tariffs with the minister of energy… in his office,” Nauryzbayev said. “These are not public hearings, so we have no idea what drives these negotiations.”

Such opaque practices could be made more transparent through open tenders, according to the expert.

In a recent speech, former minister Satkaliyev said that renewable energy capacity is poised to grow in the next few years.

“About 6.6 GW of new renewable energy capacity will be introduced through auctions until 2032. [Plus, another] 5-6 GW of new capacity will be introduced through large projects with large investors, each with a capacity of more than 1 GW,” Satkaliyev said.

The latter capacity will be built through projects such as Masdar’s wind project and Total’s wind farm.

Satkaliyev also said that these projects will “not use money from the budget.” Instead, companies will bear the costs, alongside financial institutions like the Development Bank of Kazakhstan and the EBRD.

If the past is of any guidance, however, these new projects will be set up by either public companies spending “quasi-public” money (funded by the Development Bank of Kazakhstan) or by massive corporations through government-to-government agreements, leaving little to no space for smaller investors.

Instead, industry experts suggest that commercial and investment banks should be more involved in the process in order to guarantee a proper allocation of the funds and an on-time delivery.

“The best way forward is with private finance. Because when you have privately-financed projects you cannot increase the budget at will. Let's say that a 10 MW project is projected to cost €10 million. The builders must stick to this price tag. They cannot just increase the budget like mad. The bank would point to the financial plan and say no,” Callens said.

By making banks bear a financial risk within the project, Callens argues, construction will get done faster.

“Once the project kicks off, the bank would become anxious to see the project done and the first kWh delivered, with the money it has allocated.”

In looking at Kazakhstan’s geography and electricity consumption, experts consider it important to decentralize the production base. This, however, is being planned without renewables in mind.

“Recently the authorities came up with the concept of cluster development of the energy sector. The state said that they will develop everything: coal, nuclear, and renewable energy. This is a funny situation: why would our consumers support more expensive sources?” Nauryzbayev said.

Lastly, one of the structural drawbacks is the aging electricity infrastructure, which reduces profitability due to network losses that are far above the 5% guidance set by the International Energy Agency.

“Corporations will not invest in some of these projects due to the massive network losses: around 10-15% of the energy is wasted every 100 km. And this is inevitable because the network is located too far from some regions where there is potential for wind energy,” the industry insider told Vlast. “Only the government can afford to lose money on these projects.”

The scattered nature of Kazakhstan’s renewable energy landscape essentially calls for the government to focus on building market-friendlier mechanisms, alongside commitments to optimize the grid and invest capital.

While it would have to overcome a three-pronged pressure to hold off on renewables and maintain its focus on fossil fuels, the government is still in the best position to steer Kazakhstan towards a steadfast decarbonization path, according to industry experts.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.