Читайте этот материал на русском.

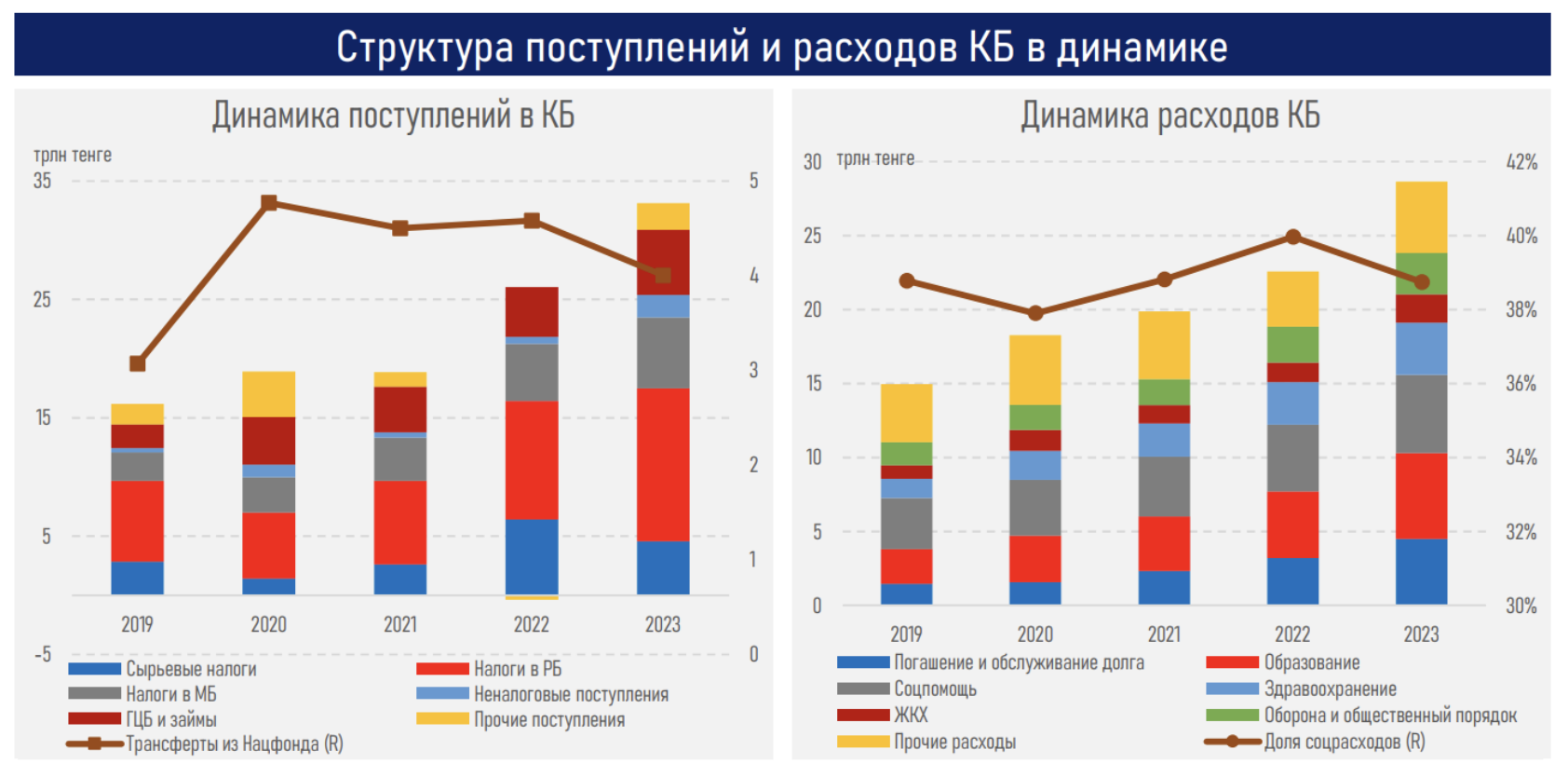

The gap between budget revenues and expenditures has grown steadily over the past five years in Kazakhstan. This explains how the deficit ballooned last year: According to various estimates, it amounted to between 4.3–11 trillion tenge ($9–23 billion) – a range so large because some estimates include the use of off-budget sources to finance government expenditures (National Fund, the Single Pension Fund, the Social Health Insurance Fund, and others). Off-budget sources, however, depend on Kazakhstan’s economic health, which in turn depends on the fluctuations in oil prices, making the whole infrastructure vulnerable.

In 2024, the government risks facing another massive deficit. Due to lost taxes, budget revenues for the first six months amounted to slightly more than half of all expenditures. Almost two-thirds of this year’s planned transfers from the National Fund have already been used to cover these expenses.

A crisis in Kazakhstan’s public finances is looming, analysts say. They argue that, by increasing budget expenditures to combat the consequences of economic crises in 2008, 2015, and 2020 (the effectiveness of which remains questionable), the state was unable to restore a moderate level of expenditures in the years after the crises.

“Most likely, the state budget is currently inflated in order to finance organizations under the ministries and other government agencies (for example, KazSportInvest, the Kazakhstan Institute of Public Development, and others). These organizations do not bring economic growth, they only provide mass employment for many bureaucrats, especially in Astana," said Sholpan Aitenova, director of the Zertteu Research Institute.

Another issue is lack of control: The Parliament cannot fully oversee government spending, especially if the decision comes through a decree signed by President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev.

Murat Temirkhanov, advisor to the chairman of the board of Halyk Finance, said this is a perverse practice that makes the budget more opaque.

“Parliament must see and approve absolutely all state finances, with the exception of those related to local budgets. [Without this, the public] will not understand how and why decisions are made on state spending,” Temirkhanov told Vlast.

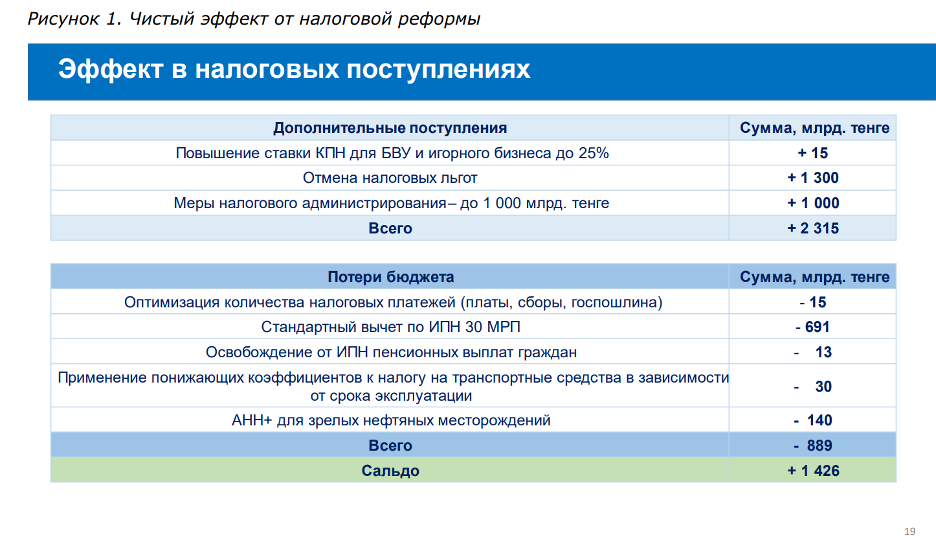

Kazakhstan’s authorities acknowledge that the imbalanced public finances are a problem, but show no rush to overhaul public spending and weed out wasteful lines of the budget. Instead, they propose raising taxes on both banks and the gambling business. At best, this will increase budget revenues by only 1.4 trillion tenge (or 6% of this year’s planned expenditures), not enough to overcome the crisis.

Experts interviewed by Vlast see a way out both through targeted changes to the Tax Code, in particular increasing the individual income tax to 16% and eliminating tax breaks, and through a new approach to budget planning.

Economist Kassymkhan Kapparov said the budget must include a safety net to weather emergencies.

“The government is stuck with too short a budget planning horizon and constant adjustments. Plus, the budget does not include a safety margin, so we regularly see the government scrambling for cash to recover from floods or power plant accidents,” Kapparov told Vlast.

Staring a Crisis in the Face

Last year, the gap between expenditures and revenues of Kazakhstan’s budget more than doubled compared to 2022, reaching 3.1 trillion tenge (or 12%).

The Association of Financiers of Kazakhstan calculated that, from 2019 to 2023, budget revenues grew systematically slower than expenditure. This prompted the state to increase the volume of public debt (in five years, a 1.7-fold increase to 5.5 trillion tenge) and withdrawals from the National Fund (20.9 trillion tenge withdrawn in five years).

But in 2023, the situation worsened. The government collected 10% fewer taxes than expected, a 2.3 trillion tenge hole mostly blamed on falling oil prices, the strengthening of the tenge, and a reduction in agricultural production.

And yet, the public learned that the budget deficit last year remained relatively small, at 600 billion tenge. A closer look, however, reveals the cracks in the system.

It was from the National Fund that the government took the money to plug the budget hole. Legal provisions, however, advise limited withdrawals from this “rainy day” fund during periods of economic growth.

In 2023, Kazakhstan’s GDP grew by a whopping 5.1%, a 10-year record. And yet, National Fund transfers continued. Last year alone, the government took 4 trillion tenge.

And then, because of a shortfall in tax collection, the government urgently withdrew 1.3 trillion tenge from the National Fund, in a complex deal to purchase a 20% stake in Kazmunaigas, the state-owned oil and gas company.

Considering both the planned and the emergency transfers, the government withdrew a total of 5.3 trillion tenge from the National Fund, which covered about 20% of budget expenditures. According to the law on guaranteed transfers, these withdrawals should not exceed 2.2 trillion tenge.

Another issue was the suspension of VAT refunds to businesses in 2023, which replenished the budget by 600 billion tenge. Adding it all up, the non-oil budget deficit was about 4.3 trillion tenge last year.

However, the real budget deficit may be much higher. Halyk Finance analysts wrote that the data published by the ministry of finance is full of imperfections. Importantly, it lacks granular, detailed information on government income and expenses.

Analysts note that the state has many other extra-budgetary financial sources at its disposal, beyond the National Fund: the State Social Insurance Fund, the Social Health Insurance Fund, the Kazakhstan Khalkina Fund, and the Fund for Problem Loans. In total, these government-owned funds spent 3.8 trillion tenge in 2023.

Along with this, the state uses assets from the Single Pension Fund to finance expenses, purchasing government bonds, as well as bonds of the sovereign wealth fund Samruk-Kazyna and the state holding Baiterek.

The government also has access to Samruk-Kazyna funds, which are used to subsidize railway transport tariffs along with gas and electricity prices, a price tag of 1.2 trillion tenge in 2023.

In addition, last year the National Bank issued 466 billion tenge to finance government spending.

All this adds up to a non-oil budget deficit of approximately 11 trillion tenge, according to Halyk Finance analysts.

In 2024, the deficit is poised to increase further due to declining tax collection. In the first half of the year, the state received 1.6 trillion tenge less than planned. State revenues stood at 5.6 trillion tenge, against expenditures of 10.6 trillion tenge.

Extra-budgetary sources like the National Fund continue to bridge the gap. Yet, since the beginning of the year, the budget has already withdrawn 3 out of 4 trillion tenge planned for this year for the National Fund. The government is likely to propose additional withdrawals from the National Fund to fulfill all budget obligations.

Weathering the Storm

According to Zertteu’s Aitenova, the development of the crisis in public finances can be tracked by the dynamics of withdrawals from the National Fund to overcome economic crises.

She points to the global financial crisis of 2008 as the starting point. In 2008-2009, the government transferred almost 1 trillion tenge (about $20 billion at the time) from the Fund to the budget to make up for extra expenditures. The bulk of these funds went to saving banks, a plan that was not discussed with the public and was not put to a referendum. The next stage of withdrawals was the commodity crisis of 2015, when around $10 billion were allocated to support the economy in the situation of collapse in oil prices.

In 2017, the government had to “finish healing” the banks it deemed “systemically important,” pumping another 2 trillion tenge in public money into the financial sector. And during the COVID-19 pandemic, the budget withdrew another 5.4 trillion tenge from the National Fund.

“But where budget expenditures grew, the revenues did not keep up. Now, expenditures increase faster than we can withdraw from the National Fund. This provokes a budget imbalance,” Aitenova told Vlast.

Kapparov added that along with the withdrawals from the National Fund, the sovereign debt is also growing, especially since the Nurly Zhol program to modernize infrastructure was launched in 2014.

Today, expenses for servicing and repaying the national debt make up 26% of all budget expenditures. Within the national debt, a major role is played by the assets of the Single Pension Fund, which are withdrawn as short-term loans to close cash gaps in the budget every quarter.

Over the last decade, Kazakhstan has financed major projects, primarily infrastructure projects, mainly through loans from international institutions like the EBRD and the World Bank: These loans are either US dollar-denominated, in which case they are subject to exchange rate fluctuations, or tied to inflation rates. Today, these loans account for 10% of budget expenditures.

“When budget revenues grow, these loans can be repaid. But when the state budget goes in the red, risks increase. In this case, Kazakhstan may need to restructure loans. But creditors will not agree to this, because Kazakhstan has the National Fund,” Kapparov explained.

Halyk Finance’s Temirkhanov, in turn, focused on the long-standing problem of political promises during elections and annual messages to the people, which always promise the growth of budget expenditures on increasing salaries, medicine, agriculture, and other items.

“All these expenses are necessary for the development of the country. But we at Halyk Finance have never seen anyone put them together in a single long-term budget strategy and look at how budget expenditures are balanced with revenues,” Temirkhanov said.

Kapparov argued that National Fund assets could be at risk if the government continues to use them to buy shares of national companies – last year Kazmunaigas, this year KazAtomProm.

“Tokayev said the plan was to grow the National Fund's assets to $100 billion, but even avoiding their shrinking is questionable. The National Fund is gradually turning into a holding of securities of national companies, which may lose value over time," Kapparov said.

Aitenova questioned whether large withdrawals from the National Fund and the growing national debt (could grow a further 5% this year) are really stimulating economic growth – something that could eventually bring new tax revenues into the budget.

“If we ignore it, we could end up with a budget crisis where we won’t be able to provide basic things, such as government services, education, and the maintenance of the government apparatus,” Aitenova said.

A Way Out?

The government has admitted there is a problem. Former prime minister Alikhan Smailov, now the chairman of the Supreme Audit Chamber, criticized the budget policy in June.

“In recent years, expenditures have significantly grown. At the same time, their coverage with non-oil revenues stays at around 50%. The remaining gap is mainly covered by transfers from the National Fund and borrowing. Therefore, it is not enough to simply maintain the deficit. Long-term plans for the formation of a deficit-free budget are needed,” Smailov said, making reference, inevitably, to his own drawbacks, having left the top government job only in February.

Senate Speaker Maulen Ashimbayev also commented on the situation and suggested the following solution: “We need to bring expenses closer to income and optimize and reduce some positions somewhere. And we need to honestly say that we will not collect so much corporate income tax, because businesses are not developing. We will not collect VAT either.”

So far, however, there have been no budget cuts, Aitenova said.

“The system does not want to change, it has become bigger and more rigid. And the fact that we are not touching expenditures is a big problem. There is a huge corruption component in it.”

For now, the government has only proposed solutions via a new Tax Code, which would hit banks and gambling businesses with higher corporate tax, abolish some tax breaks, and improve tax collection.

The government expects that these measures would bring in an additional 1.4 trillion tenge, an optimistic figure, according to Kapparov:

“The question is whether the authorities will be able to navigate this process. Most likely, this will lead to the fragmentation of business, the transfer of assets [abroad], or going into the shadows. As a result, businesses will optimize taxes, and the government will not collect the required amount.”

Both Kapparov and Temirkhanov argue that one possible solution via the Tax Code would be to resume the discussion of raising the individual income tax from 12% to 16%, because its collection is easy to administer and it will still remain low by international standards.

According to Temirkhanov’s calculations, this will bring an extra 2.5 trillion tenge to the budget. And possible negative effects for the population can be mitigated by introducing a progressive income tax as well as by increasing the social tax for businesses.

“Now everyone says that taxes cannot be raised because everything will collapse. But in the past, we were actively developing even with higher taxes. Then the authorities lowered them so that there would be less shadow economy and more production volumes, so that diversification would increase. But none of this happened. That is, the problems were not in taxes, but in the model of development of the economy of Kazakhstan,” Temirkhanov said.

At the same time, Temirkhanov is convinced that the crisis cannot be overcome by raising taxes alone. The key solution should be to increase the role of Parliament in the budget process. Currently, the president and the government bypass Parliament when they decide to increase social spending or to use off-budget sources of financing:

Aitenova believes that stability in budget planning must be achieved.

“The budget is approved in each December for the next year, and come every spring or summer the government inevitably adjusts it to solve immediate problems such as raising salaries for public sector employees due to high inflation. This creates the need to seek additional revenue for the budget,” Aitenova said.

According to Kapparov, the budget planning process needs to be improved, especially in light of a rapid population growth, which is not always taken into account. The government will have to increase social infrastructure, such as schools and hospitals.

And the Tax Code, which is now being discussed, according to him, should focus on stimulating the economy: “The new version still lacks mechanisms that would allow businesses to grow larger and ultimately bring more taxes and investments into the economy. Instead, the government is driving itself into the trap of tunnel vision, when the only task will be to balance the budget.”

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.