Joanna Lillis, for Vlast

The trial of 22 people accused of fomenting deadly violence in Uzbekistan’s autonomous Karakalpakstan region last summer reached a dramatic end this week, with defendants weeping tears of contrition as some received long sentences and one woman fainted as emotions ran high in the courtroom.

The court concluded that Uzbekistan had fallen victim to a separatist plot to break Karakalpakstan off from the rest of the country. This was despite all the defendants – even those who admitted guilt – denying the existence of any conspiracy, and prosecutors offering no proof of anyone hatching the sinister scheme.

The ruling was precisely the conclusion Tashkent desired, for the alternative is uncomfortable: that civil unrest which killed 21 people spiraled out of spontaneous anger over botched constitutional reforms launched by President Shavkat Mirziyoyev in a potential bid to extend his rule.

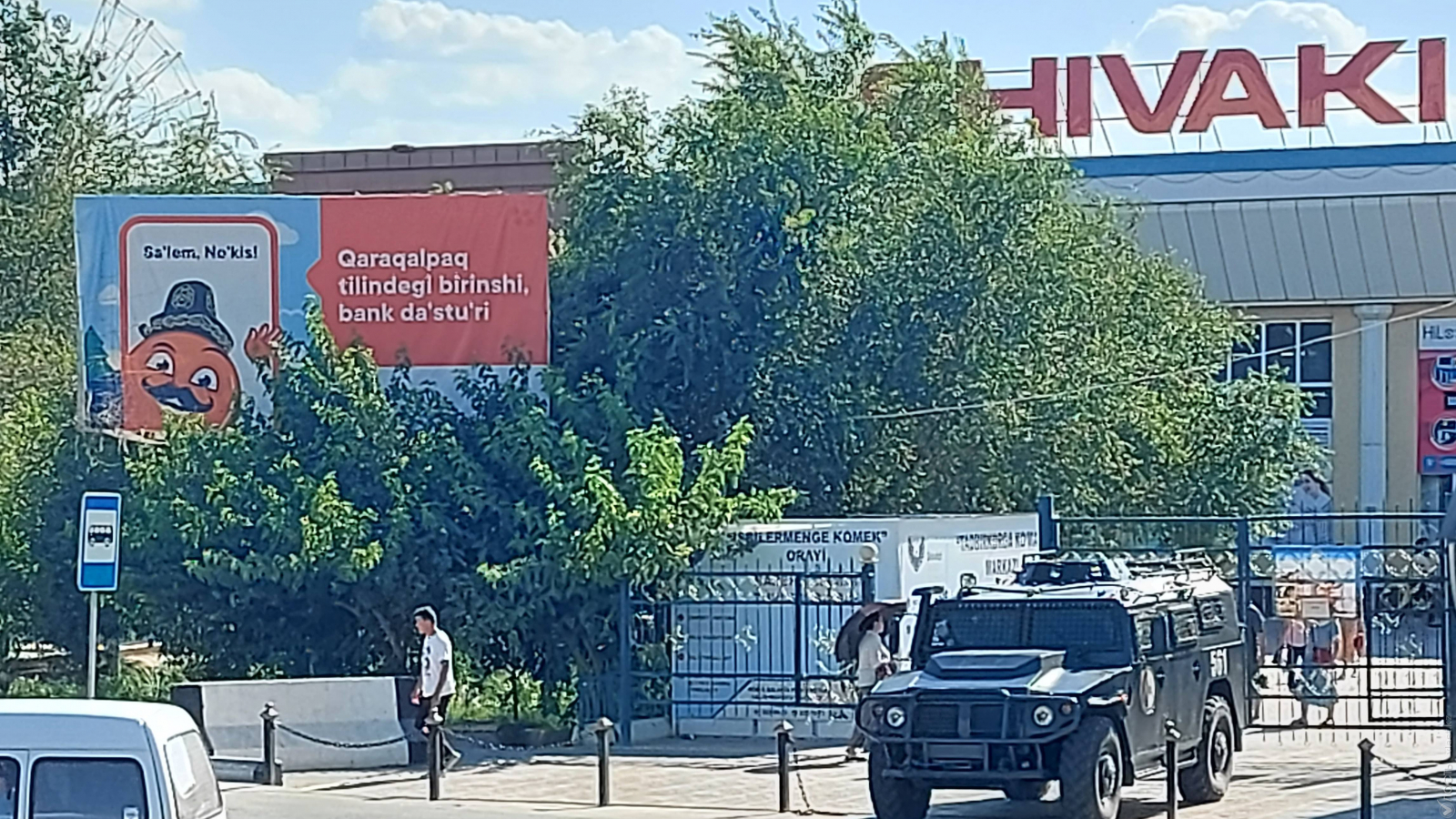

Turmoil erupted when the Karakalpaks realized that Mirziyoyev’s constitutional reform plans would affect Karakalpakstan’s autonomous status and strip them of their right to seek independence from Uzbekistan. The court glossed over this crucial detail.

Tashkent clearly sees this landmark trial as a way to draw a line under violence that seriously dented Mirziyoyev’s image as a reformer. But while some observers lapped up the government line that these proceedings were a model of transparent justice, others expressed concerns about the fairness of the trial – and lack of accountability over the deaths of civilians at the hands of security forces.

Clinging to Power?

Mirziyoyev floated the idea of amending Uzbekistan’s constitution in 2021, as he embarked upon his second five-year term of office, his last under the current Constitution. This he depicted as part of his efforts to build a democratic “New Uzbekistan” to replace the dictatorship he inherited from his tyrannical predecessor Islam Karimov, who died in 2016. His suggestion immediately sparked speculation that he planned this as a backdoor means of staying in power beyond 2026, via a mechanism favored by Central Asian presidents whereby the adoption of a new Constitution allows them to recount terms from zero and stand for re-election.

Sodiq Safoyev, the deputy speaker of the Senate, later confirmed the suspicion, saying that “all citizens, including the current president” could run in elections under a new Constitution, which could pave the way for Mirziyoyev to stay in office until 2040.

Initially, the proposed amendments did not focus on Karakalpakstan’s autonomous status. The government sprang this as a surprise in a draft of the proposed changes published in June 2022. For the Karakalpaks, an ethnic minority whose language and culture differs from those of the Uzbeks, the most incendiary proposal was to strip them of their right to call a referendum to secede from Uzbekistan. Though never exercised, this right was jealously guarded.

That the government proposed “constitutional amendments about depriving Karakalpakstan of its sovereign status and abolishing the right of the republic’s residents to a referendum on seceding from Uzbekistan” was the main reason behind the protests, explains Aqylbek Muratbai, an activist from the Karakalpak diaspora based in Almaty. Broader factors that ripened the protest mood included the blighted environment in a region that is home to the shrunken Aral Sea, profound socio-economic problems and resentment over what Muratbai calls the “Uzbek-ification” of Karakalpakstan.

Heated debates broke out on social media, which the government tried to stem by blocking the Internet.

Spiral of Violence

But the catalyst for the violence was the arrest of Dauletmurat Tazhimuratov, a 44-year-old lawyer, journalist and blogger who had long been a thorn in the side of the authorities, after he announced plans to apply to legally hold a peaceful rally against changing Karakalpakstan’s status. This would later be held against him in court, dressed up as part of a purported separatist plot. Anger erupted over his detention, beginning in the bazaar in Nukus, where traders and shoppers rushed onto the central forecourt to protest. As thousands took to the streets to demand Tazhimuratov’s release, the authorities set him free and took him to the bazaar in an effort to calm the crowds, where he received a hero’s welcome.

He was captured on video urging calm and telling protesters this was not a legitimate way to seek independence – if indeed this was what they were doing. Some of those who took part said they simply wanted to retain the status quo; others had a push for secession in mind. One was Lolagul Kallykhanova, a prominent journalist who published a video address calling for her countrymen to seek independence, and was soon arrested. Tazhimuratov was later detained again.

From the scant verified information available, the violence broke out at night, after the crowd had marched towards the seat of the Karakalpak government and parliament, where fierce clashes erupted between security forces and demonstrators. Both sides blamed each other for starting the violence, which spread around Karakalpakstan and continued into the next day and a second night. While video evidence did emerge of protesters attacking law-enforcement officers, the protesters came off far worse as live fire and stun grenades were deployed: of 21 dead, 17 were civilians. Human Rights Watch (HRW) later published a damning report alleging that the security forces had “unjustifiably used lethal force” against “mainly peaceful demonstrators”.

“Uzbekistan owes it to the victims to properly investigate how this happened and to hold accountable those responsible for serious violations,” HRW’s director of the Europe and Central Asia division Hugh Williamson said. Government promises to investigate have so far come to nothing. Furthermore, official inaction over claims that police tortured detainees, made by Tazhimuratov among others, is “highly worrying” and “raises the serious concern that evidence tainted by torture or other prohibited ill treatment may have been accepted at trial”, said Mihra Rittmann, HRW’s senior Central Asia researcher.

Divide and Rule

Convicting all 22 defendants on January 31 after a two-month trial, the court handed the longest sentence to Tazhimuratov, who received a 16-year prison term on charges of plotting to seize power and overturn the constitutional order; organizing mass unrest; possessing material threatening public order; and money-laundering and embezzlement. The first charge “harkens back to the era of President Islam Karimov”, HRW noted, “when human rights defenders and others were sentenced to lengthy prison terms in politically motivated trials”.

Tazhimuratov had vehemently denied all the charges against him. In his final impassioned speech to the court he dismantled the prosecutors’ case, based on testimony of other defendants and circumstantial evidence. Tazhimuratov drew attention to holes in the prosecution’s case, including missing evidence from video cameras in Nukus, the epicenter of the violence, that he believed would have exonerated him. He highlighted contradictions in witness testimony, which he had challenged throughout the trial, once causing a female witness to burst into tears and admit to fabricating testimony about payments made to protesters.

“I did not try to achieve independence,” he told the court.

In their rush to condemn separatist tendencies, the authorities have ignored that the right to seek independence is a constitutionally-protected one for the Karakalpaks. And, since Mirziyoyev shelved the changes affecting its status when violence broke out, it still remains so.

Other defendants rushed to admit guilt and blame Tazhimuratov as the ringleader. Kallykhanova, a well-known journalist respected for setting up Karakalpakstan’s only independent – now shuttered – news outlet, accepted responsibility for inciting incendiary feelings with her appeal for independence, and asked “forgiveness from those who lost their children.” But she hinted at official responsibility, too. “No-one paid attention, no-one got involved,” she said, citing inaction by the government and the Karakalpak parliament, whose then-head, Murat Kamalov, “never mixed with the people and took no interest in their concerns”.

Kallykhanova was one of six defendants rewarded for their demonstrative shows of contrition with non-custodial sentences. Other defendants received prison terms of up to eight and a half years.

Mirziyoyev’s “modern Uzbek renaissance turned into a revival of late dictator Karimov policies of ruthless suppression of dissent,” tweeted Sweden-based rights campaigner Muzaffar Suleymanov after the verdicts.

It was “important” that the trial had been open to journalists and observers, Rittmann said.

Meanwhile, in Kazakhstan, five Karakalpak diaspora members who had criticized the constitutional amendments remain in detention following their arrests on Uzbek extradition warrants on suspicion of involvement in the unrest. There are glaring holes in their cases: 55-year-old cardiologist Raisa Khudaibergenova was at work in Almaty when, according to her charge sheet, she was fomenting riots in Nukus, 2,000 kilometers away. Late last year Kazakh courts remanded the five in custody for a year while extradition proceedings grind on.

End of an Era?

Mirziyoyev’s reform package, including the high-handed plan to reform Karakalpakstan’s status without consulting the Karakalpaks, was the spark that led to the turbulence. Yet his administration shrugged off responsibility, claiming the initiative came from the Karakalpak corridors of power –implausibly, in Uzbekistan’s top-down system.

For some observers, the tragedy marks a turning point in Mirziyoyev’s rule. “History is usually divided into eras which have a beginning and an end,” said Muratbai, the Almaty-based activist.

“There may be more economic reforms in Uzbekistan, but the short era of Mirziyoyev’s political reforms, I think, ended with last year’s attempt to reset to zero his presidential terms and remove Karakalpakstan’s sovereignty. And it was the blood of those who died in Nukus who placed the full stop on this mini-era.”

Joanna Lillis is an Almaty-based journalist reporting on Central Asia and the author of Dark Shadows: Inside the Secret World of Kazakhstan.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.