Around 98% of Kazakhstan’s oil is exported via Russia and despite attempts to diversify export routes, the geographic dependency on the massive neighbor is here to stay, experts argue.

Key Points

- For decades, Kazakhstan said it wants to diversify the routes it uses to export its oil, but it still depends on transit via Russia.

- Pipelines through Russia are under constant threat of sanctions from the West.

- Viable alternatives would need investment and time, while transit via Russia remains key.

- Any information about oil sales via non-Russian routes, though marginal, will be hailed as a success, mostly as a reassurance for Western partners.

After the beginning of Russia’s war in Ukraine, Kazakhstan’s government tried to set itself apart and continue trading with its Western customers as before. In the spring of 2022, the government decided to establish a new “brand” under which to sell its oil, Kazakhstan Export Blend Crude Oil (KEBCO).

In recent months, the government also hailed new agreements with Germany and Azerbaijan for the shipment of its oil as landmark, as well as meticulously counting and releasing to the press each of the barrels it exported via the new routes.

To Germany, via the Soviet-era Druzhba pipeline through Russia, since February Kazakhstan exports marginal amounts of the KEBCO oil blend - a total of 1.2 million tons are planned for this year, but just 290,000 tons were shipped in the first half. The crude is then processed at the Schwedt refinery, which is co-owned by Russia’s Rosneft, British-Dutch Shell, and Italy’s ENI.

Because of a halt in Russian supplies, Kazakhstan’s oil became key for the Schwedt refinery’s continued operations. In an effort to diversify its sources, on July 11 the refinery asked the German government for €400 million in aid to upgrade the Rostock-Schwedt pipeline that supplies the refinery from the port in northern Germany.

After the adoption of the European Union’s 11th sanctions package against Russia on June 23, a temporary permission to import Russian oil through the northern section of the Druzhba pipeline into Poland and Germany expired, leaving only oil originating from Kazakhstan into the massive pipeline.

Options Via Azerbaijan

One of the potential alternative transit routes for Kazakhstan’s oil exports could be Azerbaijan, but this is far from being a viable option, experts and data analysis showed.

In the second quarter, Kazakhstan’s pipeline monopolist KazTransOil said it increased shipments from the Tengiz giant field in the west of the country across the Caspian Sea to Baku and further through the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) a pipeline that pumps oil to a port in the south of Turkey, where traders pick it up and ship it further via sea tankers.

The BTC, built in 2005, had intermittently hosted Kazakhstan’s oil in its pipes. In the first six months of 2023, its flow increased overall by 6.6% compared to last year, the company said. In the same period, however, the contribution of Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan to the pipeline only grew by 3.8%, accounting for just 12.5% of the pipeline’s total capacity.

These volumes are poised to remain marginal, oil industry expert and research fellow at the University of St. Andrews, Aliya Tskhay, told Vlast.

“We will see increased shipments through the BTC and through other existing routes, but the quantity is so minimal that it’s almost negligible. It won’t change much for Europe, in terms of their energy crisis, and it certainly won’t make for a significant income jump for Kazakhstan either,” Tskhay said.

In late June, Kazakhstan signed an agreement with SOCAR, Azerbaijan’s state-owned oil company, to increase the quota of the BTC pipeline it could use from the current 1.5 million tons annually. The government did not disclose the quota allocated in the new agreement.

In the absence of a pipeline from Aktau to Baku, Kazakhstan’s oil can only reach across the Caspian via tanker. And the fleet at the moment could not shoulder a serious increase in shipments.

“To make it across the Caspian, Kazakhstan’s oil would either require beefing up our fleet of tankers, which is far from feasible in the short term, or building new pipelines, which are expensive infrastructure projects, and foreign investors are not necessarily keen on coming to Kazakhstan with the political situation and the business climate that we currently have. Also, negotiating and building new infrastructure needs years to complete,” Tskhay added.

In March, Japan’s INPEX sent a test batch of 7,000 tons of oil from the giant Kashagan field through the BTC. The experiment, however, has not been repeated so far.

Russian Oil Through Kazakhstan’s Pipelines

Statistical data presented at the Argus Media conference on Kazakhstan’s oil and gas industry, held in Almaty in June, showed that even when used at maximum capacity, existing alternative routes would allow Kazakhstan to export only around 20-25 million tons of oil annually. For a comparison, routes through the Russian territory are being used to export around 65 million tons per year.

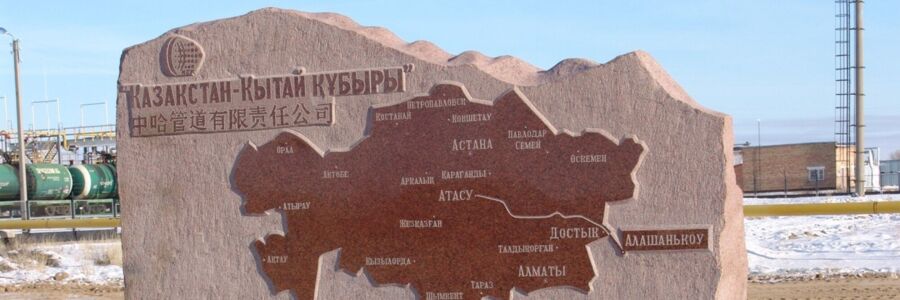

And Russia is also using Kazakhstan’s pipeline system to export its own oil. The Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline, with a 20 million ton capacity, is currently being used, below capacity, to pump around 10 million tons of Russian oil from Siberian fields north of the border with Kazakhstan.

Russia and China have a long-term oil trade agreement and its lack of export capacity via other routes has led Russia to ask Kazakhstan for permission to transit oil through the KazTransOil pipeline system. In 2022, only around 1.2 million tons of Kazakhstani oil reached China.

In addition, KazTransOil said it resumed this year the transit of Russian oil destined to Uzbekistan, although it only represents a marginal volume at around 350,000 tons in the first half of 2023. The company also agreed with the Russian government to transit oil destined to Kyrgyzstan.

With Kazakhstan as a key transit route for Russian oil, and vice versa Russia being a key transit route for Kazakh oil, the two countries are still as intertwined as ever.

The most important pipeline outlet for Kazakhstan’s oil, in fact, is the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC), which runs from the fields in western Kazakhstan to Russia’s Novorossiysk port on the Black Sea. The CPC transports 80% of Kazakhstan’s oil exports.

Since the start of the war, industry experts have wondered whether and how Western countries would have included the CPC in the sanctions list, since it also transports Russian oil, which is blended into the pipeline with the Kazakh crude, making it indistinguishable. So far, the pipeline has managed to escape sanctions, but certain EU-based actors, such as Deutsche Bank, have gradually cut ties with the Russian legal entity that makes up half of CPC.

In its 11th sanctions package, however, the EU has ruled that maintenance equipment for the CPC could be sold to Russian customers without consequences.

Despite the relative regulatory calm, the CPC has suffered repeated interruptions in 2022, mostly caused, according to official statements, by inclement weather at the marine terminal, but arguably also tied to diplomatic spats. Any disruption in the flow of oil through the CPC could be detrimental to Kazakhstan’s budget.

Breakdowns and Stitches

On July 3, an emergency shutdown at MAEK, a major power plant in the western Mangistau region, caused a massive blackout and brought operations to a halt at the Atyrau refinery, majority-owned by Kazmunaigas, and at several pipeline pumping stations operated by KazTransOil and CPC. A daily drop of 21% in oil production was registered on July 4.

MAEK, owned by the Mangistau regional administration, is responsible for heating and electricity for a wide area of the Mangistau and Atyrau regions. Its failure led the government to question the grid’s readiness to withstand emergencies.

Each oil extraction operation and several of the connected industrial facilities have their own power generating infrastructure, with the notable exception of the Atyrau refinery.

Electricity generated by the facilities linked to the Kashagan field - which were briefly affected by the July 3 outage - was injected into the main grid, effectively helping to restore power supplies.

The ailing local power infrastructure could represent another risk factor for Kazakhstan’s oil exports, besides the existing worries about sanctions against pipelines through Russia or supply interruptions, as it happened repeatedly with the CPC.

“Kazakhstan’s infrastructure crisis is clearly the result of years of neglect of critical physical infrastructure,” Ben Godwin, director of analysis at London-based PRISM Political Risk Management, told Energy Intelligence last week. “Corruption must be a part of this story.”

Industrial Recognition

Starting in August, Platts, a company that sets industrial standards in the petroleum industry, will launch new assessments of the KEBCO blend, a move that would allow Kazakhstan’s exporters “to receive fairer valuation conditions, which will improve their negotiating positions in the global market,” the KAZENERGY lobby group said in a statement.

At the Argus Media conference, several company officials openly lamented that KEBCO, which has traded at prices above Russia’s flailing Urals blend, has not been actually used by traders, who still refer to other price benchmarks when drafting up contracts.

Oil and gas - but mostly oil - represent the backbone of Kazakhstan’s exports. In the first four months this year, hydrocarbons accounted for around 75% of total exports according to the World Bank. But while oil sales were up in terms of volume, the income that extractive companies garnered was lower than the same period last year, because prices have declined.

And finding new routes might not ultimately change much for the pockets of oil and gas companies.

While several media reports have argued that exports bypassing Russia have “ramped up”, the reality is that quantities that find alternative routes still represent a drop in the bucket.

“Alternative routes were always discussed within the government’s narrative of diversification of transit routes. At the same time, nothing was practically or technically developed, and these plans were not tied to actual capital investment,” Tskhay said.

“Pipelines are not made out of rubber,” Tskay said, hinting that the capacity of alternative routes cannot be expanded at will, without accounting for significant investment and construction time.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.