- ВКонтакте

- РћРТвЂВВВВВВВВнокласснРСвЂВВВВВВВВРєРСвЂВВВВВВВВ

In early 2022, during the so-called January Events, former-President Nursultan Nazarbayev quit his post as chairman of the National Security Council. He was also later stripped of the Father of the Nation (Elbasy) legal status granting him and his family a range of privileges. President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev also indirectly criticized Nazarbayev when he pointed out that it was under his rule that “a group of people who are rich even by international standards appeared”. Almost three weeks after the initial protests broke out, Nazarbayev appeared on television meekly saying he was “just a pensioner”.

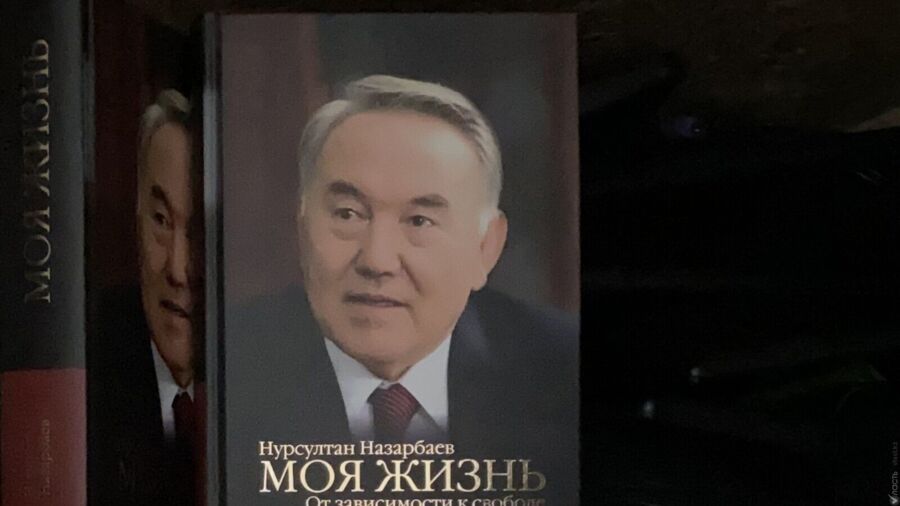

In his latest 700-page autobiography, “My Life”, Nazarbayev dedicates one chapter to the January Events, commonly also known as Qandy Qantar (Kazakh for ‘Bloody January’, a reminder of the violent repression of urban protests). The people at the time called for him to leave the political scene, but how does Nazarbayev remember Qandy Qantar?

Ignoring the Victims

“The road of history is difficult at all times. This was evident during the events of January 2022,” Nazarbayev opens, in a chapter just called “January”.

Nazarbayev follows this with a sentence that parrots earlier statements by Tokayev: “organized extremist groups staged mass unrest in the country and carried out terrorist attacks.” The former president writes unequivocally that “extremists” and “riotous crowds” seized administrative buildings, the Almaty airport, and gun stores while attacking law enforcement officers and beating up residents.

He skips the part where Tokayev gave the “order to shoot to kill without warning” and where special forces violently dispersed protesters across the country. Nazarbayev is also silent about the victims, including four-year-old Aikorkem Meldekhan (the officer who was accused of her killing was recently acquitted), and about the people who suffered torture while in detention.

Nazarbayev said he had to watch all this from the side, failing to acknowledge his role as the leader of the country for three decades.

Shifting the Blame

The space dedicated to the events pales in comparison to the number of words Nazarbayev dedicates to the causes.

“At all times, some people are unhappy for some reason. Life without difficulties does not exist,” says the former president, whose family members became wealthy during his reign.

What made it more difficult, Nazarbayev argues, were “alarming trends of a global nature”, such as a decrease in export revenues and the coronavirus pandemic, which “took a toll on people and frayed their nerves.”

He also acknowledges the issue of the national currency’s devaluation during his reign, which led to an increase in the price of essential goods. And yet he fails to describe his own role in the devaluation of the tenge. For example, he called the 2014 devaluation useful for the economy and argued that it was done in order to “improve the economic situation of our enterprises.” He confidently stated that devaluation “would not affect ordinary citizens in a negative way.”

When Nazarbayev had words of contempt about the “serious shortcomings” in the work of the government, he pointed to the dismissal of prime minister Bakytzhan Sagintayev, one of his last moves as president.

Those shortcomings made Nazarbayev simply “demote” Sagintayev to mayor of Almaty.

Someone’s Always Unhappy

When focusing on the people who showed dissatisfaction towards the government’s policies, Nazarbayev simply states that “such groups always exist.” He notes that the “protest vote” for Amirzhan Kossanov in the 2019 presidential elections was an indicator of the consolidation of dissatisfied groups. Officially, Kossanov received 16.2% of the votes.

“There had never been a case where a representative of the opposition received so many votes in a presidential election before this. Frankly speaking, after the 1999 presidential elections, in which Serikbolsyn Abdildin ran, no other serious rivals appeared,” writes Nazarbayev.

But for around 30 years, representatives of the opposition were persecuted, political protests were harshly suppressed, and parties and movements were routinely denied registration.

Despite changes in legislation, very little has changed since Nazarbayev’s exit: The opposition still cannot register their parties and rallies lead to detentions and preventive arrests.

Power Plays

The main reason that led to the clashes of Qandy Qantar was a “struggle for power,” Nazarbayev claims.

“In 2019, when I voluntarily resigned my presidential powers and, in accordance with the Constitution, transferred them to the Chairman of the Senate, many took this with hostility, which I know for certain.” Nazarbayev writes “Some of those who were (secretly, of course) against my decision to choose a successor, dreamed of taking the post of president”.

Nazarbayev also notes that he was ready to hand over the chairmanship of the Security Council to Tokayev.

“I personally and voluntarily transferred power to my successor. Why would I need to keep just a piece of power when I could have continued as president, given the people’s full support (as the 2015 elections showed),” he writes.

Tokayev, however, had said in January 2022 that he decided to replace Nazarbayev as chairman “literally on the fly.”

Pointing Fingers

In his autobiography, Nazarbayev argues that the January Events were an attempted coup that had been prepared throughout 2021.

In the book, he reprints an answer he gave to Vlast after casting his ballot at the 2022 presidential elections. He draws a comparison between the former chairman of the National Security Committee, Karim Massimov, and Judas, while he plays the part of the betrayed Jesus.

One year after the events, Massimov was named “the main organizer of the attempted coup” and later sentenced to 18 years in prison.

The former president’s sworn enemy, the leader of the banned Democratic Choice of Kazakhstan, Mukhtar Ablyazov also features in the roster of those whom Nazarbayev accuses of fueling the violence.

“Radical opposition finally revealed its true face during the tragic events of January 2022. From the very beginning of the protests, Ablyazov called on protesters to ‘coordinate actions’ [...] He openly talks about his involvement in the bloodshed. He speaks with pride and satisfaction. He perceives people's suffering as his victory in politics. What cynicism,” writes Nazarbayev.

He draws a line between the natural inclination for the opposition to criticize the authorities and the call on the demonstrators to take to the streets to violently seize power.

“The name for this is banditry and terrorism,” Nazarbayev concludes.

Self-Praise

Despite not-so-veiled criticism from Tokayev in the first months after Qandy Qantar, in his book Nazarbayev continues to support his successor. He mentions one rare sentence of praise by Tokayev, who said of him that “our first president did a great job of turning the country into a strong state.”

Nazarbayev writes that Tokayev’s assessment “was a great encouragement.”

In closing the chapter about January, Nazarbayev writes: “For a population to overcome this and retain their inner core, it means that they are strong. There is no doubt that our country has a bright future.”

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.