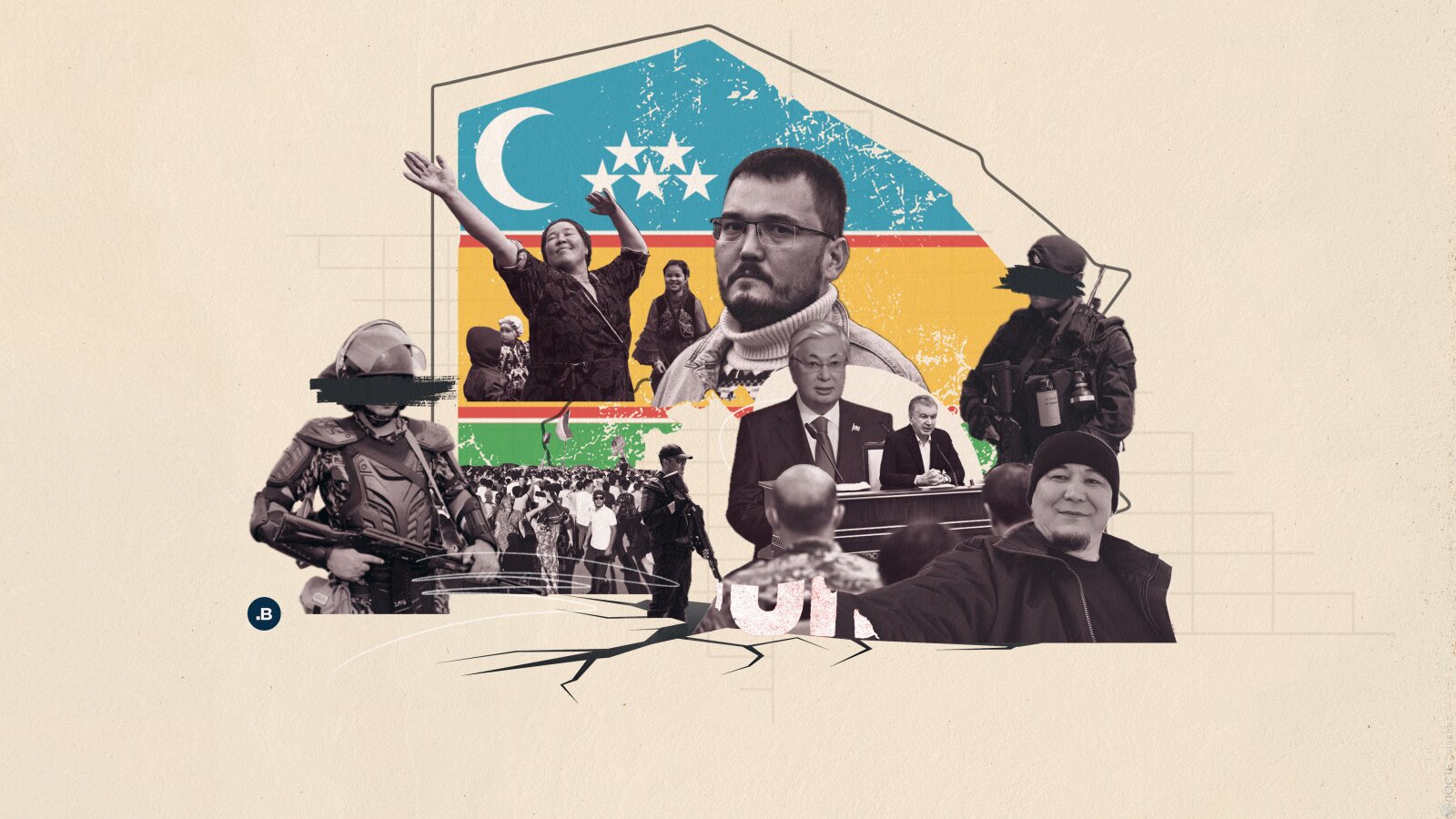

Ethnic Karakalpaks living in Kazakhstan have become the target of detentions and pressure after the July 2022 protests in Nukus, the capital of the autonomous region in Uzbekistan’s north-east. Uzbekistan’s government demanded that activists detained in Kazakhstan be extradited, after accusing them of “calling for mass riots” and “attacks against the constitutional order.”

Those who were detained had posted videos and published appeals on social media calling for an independent investigation of the violence of the summer of 2022.

Five of the activists spent a year under pre-extradition detention in Kazakhstan, although they were ultimately not extradited to Uzbekistan. Yet, Kazakhstan’s government rejected their applications to be considered political refugees. Once freed from detention, some activists tried to obtain asylum abroad, while others still remain in Kazakhstan.

Vlast spoke with activists of the Karakalpak diaspora and human rights defenders about their past legal quests and what future awaits them.

Осы мақаланың қазақша нұсқасын оқыңыз.

Читайте этот материал на русском.

Not so Sovereign

According to Uzbekistan’s Constitution, the region of Karakalpakstan is a sovereign republic, with its own institutions. Around two million people live there. Proposed amendments to the Constitution in 2022 threatened Karakalpakstan’s legal status, leading to popular protests in Nukus that were violently repressed In July 2022.

During the clashes between security forces and protesters, at least 21 people were killed.

Activist and journalist Dauletmurat Tazhimuratov was one of the first to speak out against the constitutional amendments and was singled out as the instigator of the unrest. He was detained in July 2022 and sentenced in January 2023 to 16 years in prison along with other people.

Pressure and persecution had been an integral part of the life of Karakalpakstan activists even before the July 2022 protests. People who openly expressed their opinions about Karakalpakstan’s sovereignty had been arrested and, in some cases tortured both under former President Islam Karimov and under his successor Shavkat Mirziyoyev.

Silencing Dissent

After quashing the protests in Karakalpakstan, Uzbek authorities moved to silence the voices of activists living in other countries, including Kazakhstan. The activists faced new criminal charges in Uzbekistan, whose authorities demanded extradition.

Ziuar Mirmanbetova, Tleubike Yuldasheva, Zhangeldy Zhaksymbetov, Raisa Khudaibergenova, Nietbay Urazbayev, Koshkarbay Toremuratov, and Akylbek Muratov were all involved in the Karakalpak diaspora in Kazakhstan.

Identity and Repression

The latest activist arrested in Kazakhstan at the request of Uzbekistan is human rights activist and informal leader of the Karakalpak diaspora Akylbek Muratov.

He was detained on February 15 and is currently in a pre-trial detention center in Almaty, awaiting the decision of the commission on his request for political asylum in Kazakhstan. Uzbekistan accuses him of “calling for mass riots” and “distributing material that threatens public safety.”

Muratov was mostly involved in protecting the rights of labor migrants and preserving the ethno-linguistic culture of the Karakalpaks in Kazakhstan.

“I used to focus on issues related to Karakalpaks here. So that the local Karakalpaks did not lose their identity,” Muratov told Vlast in an interview in 2022.

Born in Uzbekistan’s Navoi region, Muratov moved to Almaty in 2010.

After the events in Karakalpakstan in 2022, Muratov was summoned by the Almaty police and questioned by both representatives of the National Security Committee and law enforcement officers of Uzbekistan. They demanded that he stopped sharing video messages.

In September 2022, Muratov’s associate Koshkarbay Toremuratov was arrested. This was just the first one in a series of arrests of diaspora activists: Zhangeldy Zhaksymbetov, Ziuar Mirmanbetova, Tleubike Yuldasheva, and Raisa Khudaibergenova all found themselves behind bars in a matter of weeks.

Muratov reached out to international and local human rights organizations.

“We attract attention wherever we can. After Koshkarbay’s arrest, I could not sit quietly. I began to speak out. Arrest me, if you want, but I won’t sit in silence,” Muratov said in 2022.

Meanwhile, the chairman of the Karakalpak diaspora in the Mangistau region, Nietbay Urazbayev was put on Uzbekistan’s wanted list. As a citizen of Kazakhstan, he was not arrested.

In December 2023, however, his citizenship was revoked for not having communicated that he had given up his Uzbek citizenship. Urazbayev denied the Uzbek Consulate’s argument, saying it was just a “way of exerting pressure on him.” He moved to Almaty from Aktau for fear of being kidnapped and sent to Uzbekistan. In January 2024, Urazbayev died of a heart attack due to prolonged and severe stress.

Revolving Prison Doors

Muratov was detained after other Karakalpak activists were released after having spent a year in pre-trial detention centers. On February 23, Muratov was granted a temporary certificate of asylum seeker in Kazakhstan.

Muratov’s sister Fariza Narbekova said her brother had been preparing for his arrest for a while and warned her in advance.

“Because he was regularly summoned by the authorities, he told me to be on alert if he failed to come back after a while. But it is impossible to be prepared for this,” Narbekova told Vlast.

She was relieved when they realized that he could not be extradited to Uzbekistan.

“I am proud of my brother. He protects the rights of other people, his children. He does this for me, too,” Narbekova said.

Torture in Uzbekistan

Born in Karakalpakstan, Koshkarbay Toremuratov moved to Kazakhstan in 2006 after having worked in universities and government agencies.

“Salaries were low, there was no way to feed my family, that’s why I moved,” Toremuratov told Vlast.

In 2014, Toremuratov traveled back to Karakalpakstan because his mother was sick. At the border, he was detained by local Karakalpak police officers together with the special services of Uzbekistan, accusing him of “illegally crossing borders.”

“I was detained as if I was a terrorist. It was a special operation. But this is also how they punished people who expressed their opinions,” Toremuratov said.

He served six months in a pre-trial detention center in Nukus, where he was tortured for two weeks. Beaten and with permanent injuries, Toremuratov was then transferred to a prison in Qarshi, around 700 km to the south-west of Nukus. After the death of former President Islam Karimov, he was supposed to benefit from an amnesty called by new leader Shavkhat Mirziyoyev. But he remained behind bars.

“Every six months they charged me with some violation so that I couldn’t get out. Only in 2018, they finally asked us to write an apologetic petition to the prosecutor, to justify releasing 37 of us.”

The court had taken his passport in custody, but said it lost it. So Toremuratov was unable to travel for several months. He noted that in the end, he was advised to pay a fine and leave for Almaty.

Toremuratov set up a YouTube channel in 2019 to voice current issues in Karakalpakstan and publish videos from there.

In 2020, when he published a video of a small demonstration called by political activists, the diplomatic mission of Uzbekistan, through Muratov, told the activist to “tone it down” and praise President Mirziyoyev’s reforms instead.

“When they detained me in 2022, they referred to this video,” Toremuratov said.

Toremuratov was accused of “encroaching on the constitutional order of Uzbekistan” and “distributing material that threatens public safety”.

While in detention, he wrote a petition for political asylum in Kazakhstan. In 2023, the commission rejected the petition.

“I told my wife not to panic and said: ‘Akylmen sheshіnder’, a phrase with two meanings. I meant to say both: ‘Let’s decide with our head’ [from Kazakh ‘akyl’ - mind], and “let’s decide together with Akylbek” [Muratov].” Toremuratov said.

After his release in September 2023, Toremuratov went to Poland to participate in the OSCE Human Dimension Conference. He asked Muratov to write his speech to raise the topic of Karakalpakstan.

After the conference, Toremuratov traveled to Austria, where he applied for political asylum. But on February 29, he was deported back to Poland, because the European Union’s “Dublin Protocol” requires people to apply for asylum in the first EU country they enter.

Now, Toremuratov intends to ask for political asylum in Poland and hopes to return to Karakalpakstan someday.

“I hope that the situation will change both in Karakalpakstan and Uzbekistan,” the activist said.

“Death Awaits Me There”

Ziuar Mirmambetova, 47, is one of the activists of the Karakalpak diaspora detained at the request of Uzbekistan. She arrived in Kazakhstan in 2000, but managed to obtain a residence permit only in 2012.

“It is difficult to obtain Kazakhstan’s citizenship. This is the second time I have received a residence permit. My husband is Kazakh, my children are Kazakhs. But I gave birth to one of my daughters when I was traveling to Uzbekistan, and we can’t get citizenship for her either,” she told Vlast.

When she went to Karakalpakstan in 2019 to celebrate Karakalpak Language Day, Mirmambetova was detained together with another activist, Yerman Eskendirov.

“They questioned me, but they tortured Eskendirov. He barely survived and I managed to get him to Almaty,” Mirmambetova said.

After her younger sister died in October 2021, she went to take care of her mother in Karakalpakstan. She was detained two months later.

“They kept me until 5 January 2022. There was no court decision, no charges. I was detained just because I was an activist. They only released me after the signs of torture were gone on my body,” she recalled.

Mirmambetova went quiet on social media, avoiding sensitive topics for several months, but the proposed constitutional amendments brought her back into activism.

“We held a conference in May in Almaty. Two months later, in July, the people in Nukus protested. We are now blamed for the uprising,” Mirmambetova said.

In October 2022, she was arrested at the restaurant where she worked. She was accused of “encroaching on the constitutional order of Uzbekistan.”

After a 12-month detention, she was released. Her appeal to receive political asylum was rejected, alongside all others. Now, Mirmambetova intends to file an appeal.

“There are nine more people in my family, some of them citizens of Kazakhstan. How will I manage if I go abroad?”

Mirmambetova said the number of people leaving Karakalpakstan is increasing, despite pressure mounting against activists in Kazakhstan.

“The authorities of Uzbekistan, as well as the leadership of Karakalpakstan, are letting our people down. But our words mean nothing to them, they used violence against their own people. Now I don’t know what will happen to Karakalpakstan,” she said.

Not without sadness, Mirmambetova admitted that she is unlikely to return to Karakalpakstan.

“I know that death awaits me there.”

What’s in Store for Karakalpak Activists from Kazakhstan?

Yevgeniy Zhovtis, head of the Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights in Almaty, said there’s a political and diplomatic struggle over the topic of political asylum.

“Kazakhstan does not want to give asylum, for obvious political reasons: It does not want to spoil relations with neighboring countries. Yet, due to criticism from abroad, Kazakhstan also does not want to extradite them. Therefore, they are kept under detention while an extradition request is considered for a year. [Kazakhstan’s authorities] are playing for time until they can allow these people to leave,” Zhovtis said.

Karakalpak activists, as well as many other asylum seekers from neighboring countries, are kept in a limbo. They must be extradited in accordance with the Minsk Convention, but they are also granted a temporary asylum seeker certificate.

Kazakhstan has used this stratagem for many years, according to Zhovtis.

“Uyghurs from Xinjiang, Turkmens, and Uzbeks found refuge in Kazakhstan due to this scheme. For some time, Uzbeks were sent back to Uzbekistan, which sparked a harsh criticism from the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees,” Zhovtis said.

Leila Nazgul Seiitbek, a lawyer at Freedom for Eurasia, a non-profit that also works with Central Asian asylum seekers, said that Kazakhstan should do more.

“We understand the political motives for such behavior, but there are international obligations that the country is obliged to fulfill. And this also impacts Kazakhstan’s international image,” she told Vlast.

Besides Toremuratov’s case, Freedom for Eurasia is now also advocating for Nauryzbay Menlibayev, another activist, to receive his refugee status.

A citizen of Kazakhstan since 2013, Menlibayev traveled to Poland in 2022 to attend a human rights conference and remained there for security reasons.

After following Toremuratov’s example and applying for asylum in Austria, they were deported back to Poland on January 8. Menlibayev’s case is awaiting a decision from the European Court of Human Rights.

Seiitbek criticized European judges who rule for deportation back to Central Asia.

“The authorities of European countries do not understand that extradition is essentially a death threat for the activists. They somehow believe that Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan are safe countries to return these people to,” Seiitbek said.

“It is absolutely clear that they will not receive any justice upon their return. And there is already enough evidence to understand that these people are subjected to inhumane treatment and torture throughout their detentions.”

People from Central Asia have a hard time obtaining refugee status, according to Zhovtis. The most recent influx of refugees from Ukraine, Russia, and other countries plays a role, as well as the growth of nationalist and conservative movements.

“More right-wing governments that don’t like migrants are coming to power and are trying to push them away. The only solace is that despite refusals Central Asian asylum seekers are not being sent back,” Zhovtis said.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.