In January 2023, once it concluded a lengthy investigation, the Prosecutor General's Office offered a blunt explanation for Qandy Qantar (Kazakh for ‘Bloody January’, the violent repression of urban protests across the country): it was an attempted coup. This justified the use of weapons and disproportionate force on the part of the security forces against the participants in the uprising. Yet, human rights activists still contend that the Prosecutor’s version left several important questions unanswered, especially for the victims.

For the past two years, these activists have been involved, together with lawyers, in numerous trials against Qandy Qantar participants. We reached out to them to talk about their tireless effort in search for justice.

Not Everyone Fits the Mold

In early January 2022, peaceful protests were exploited to carry out a parallel coup, according to the government agencies - including the Prosecutor General’s Office - responsible for the investigation.

In his latest interview President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev explains that the January Events were organized by “a group of high-ranking officials” who had enormous influence within the security forces structures and criminals, and who were dissatisfied with the president’s alleged drive towards political democratization.

While the president noted that socio-economic problems were at the root of Qandy Qantar, he contends that the first protests in the Mangistau region were provoked by “inciters,” and that during the initial clashes, “law enforcement agencies” avoided the use of force – a version with which observers and journalists disagree. is not confirmed by the observations of journalists. Tokayev has also continued to argue that “outside terrorists,” connected to criminals and extremists, were the main protagonists of the events. This version has not been confirmed over the past two years, neither by any of the investigations nor by court proceedings.

Tokayev argued that “talking about an alleged popular uprising contributes to the justification and whitewashing of criminal acts,” and that these were not peaceful demonstrations, but mass riots and pogroms.

As for the organizers of Qandy Qantar, last year the Prosecutor General named former chairman of the National Security Committee (KNB), Karim Massimov, among them. In April 2023, after a closed trial, Massimov was sentenced to 18 years in prison for high treason, along with three of his former deputies.

Importantly, Samat Abish, Massimov’s first deputy at the time and nephew of former President Nursultan Nazarbayev, was not involved in these trials. In September, during another court hearing, a former KNB department head stated that Abish gave him orders during Qandy Qantar. The Prosecutor General's Office then confirmed that Abish was under investigation for abuse of power and that the trial would be held behind closed doors.

Human rights activist and founder of the NGO International Legal Initiative, Amangeldy Shormanbayev, said that the riots were initiated by special security forces, in cahoots with criminals and provocateurs, in an effort to suppress popular protests.

“When people reached the square in Almaty, 80 other towns and cities were protesting. It had become clear that this protest would continue and demand political [change]. We believe that criminal groups were used by the security services to create [a riot] and thus provide a legal basis for a forceful intervention. This is why many trials are held behind closed doors: Should they be public, the underlying strategy would become clear,” Shormanbayev said, adding that the government failed to conduct a truly independent investigation.

According to Shormanbayev, the dismissal of the initial government allegation that there were 20,000 terrorists roaming around makes the intervention of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) illegitimate.

The “Shoot to Kill” report, published in June by a coalition of human rights organizations, also found that “the level of violence in Kazakhstan does not qualify as a situation of armed conflict or as defined by the global war on terror.” Therefore, in the overwhelming majority of cases, the violent repression during Qandy Qantar was “arbitrary and illegal.”

Instead, Shormanbayev argued that the peaceful nature of the protest could not be dismissed only because “provocateurs and intelligence agents” organized riots.

Trials and prosecutions

A number of trials regarding Qandy Qantar were concluded In 2023. One of the most high-profile cases concerned the seizure of Almaty airport. Journalist Aigerim Tleuzhan was among those who were sentenced in July, and will serve four years in prison. In November, a court in Almaty upheld the verdict. Now Tleuzhan’s lawyer, Ainara Aidarkhanova, is preparing to appeal to the Supreme Court.

Aidarkhanova told Vlast that she noticed how strangers were being grouped together during criminal prosecution cases. Those convicted of the “seizure of the airport”, for example, did not know each other.

“In one case 25 ‘participants’ in Qandy Qantar were all grouped into one trial. These trials take a lot of time, and we noticed many procedural violations,” the lawyer said.

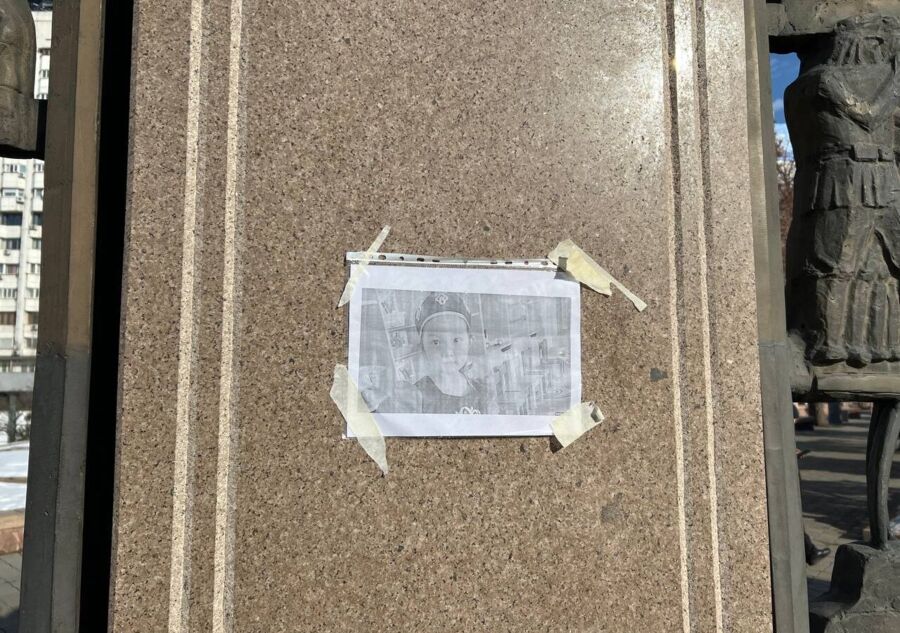

In another case, five young residents of the southern city of Taraz were posthumously sentenced in February 2023 for organizing a mass riot. Only one of them was later acquitted, but the relatives of the victims deny all charges.

“There is no justice. We proved our children’s innocence in every way. The court reached its decision in just one hour,” Nigora Zakaryaeva, the mother of the deceased Yerzhan Baizhanov, told Vlast.

Lawyer Galym Nurpeissov said he noticed a growing use of closed courts. In some cases, online closed courts make it even more difficult to follow.

“After the COVID-19 quarantine, offline trials resumed. But when the cases concerned activists, and people lined up outside the courthouses, the authorities ordered online, closed trials,” Nurpeissov said.

The lawyer also said that the government has not given a comprehensive assessment of Qandy Qantar, leaving the public in the dark.

Charged without Evidence

The trials against those accused of attacking the municipal building and the presidential residence in Almaty are ongoing. In the dock in this case were activists Kosai Makhanbayev and Nurtas Karaneyev, victims of torture while in detention. The torture cases that they had brought to court were closed and they believe these latest charges were applied to them because of their activism.

“We believed that we could achieve justice, that there would be a New Kazakhstan. They didn't like it. So they charged me in this case despite there being no evidence,” Makhanbayev said in court.

Akylzhan Kiysymbayev, another activist who suffered from torture, also found himself under criminal prosecution. On November 17, 2022, he was arrested as a suspect in “organizing mass riots” for the upcoming presidential election day.

Nurpeissov, who was his lawyer, said he believes that this case was initiated to legitimize Tokayev’s statement about the presence of “20,000 terrorists.”

“Akylzhan needed rehabilitation for his injury. It’s ridiculous to think that he could be involved in the preparation of a coup. Lots of the accused are simple hard workers, who try to get by for themselves and their families,” Nurpeissov said.

“The State Has Violated the Right to Life”

The Ar.Rukh.Khak Foundation, led by human rights activist Bakhytzhan Toregozhina, started collating an independent list of the victims immediately after the tragic events. According to their data, several passers-by were among the victims, which led human rights activists to focus on rehabilitation and compensation for them and their families. An unwelcoming legal system, however, is complicating their work.

Toregozhina said that victims were awarded compensations in only 20 out of 53 cases. Most of them were citizens who suffered arbitrary detentions and ill-treatment. For those cases in which the perpetrators of violence could not be identified, however, the current legislation does not provide grounds for compensation.

“We have now filed appeals. And we are also working with the Supreme Court to initiate amendments to the law, because relatives of those killed should have the right to compensation,” Toregozhina told Vlast.

The foundation has repeatedly requested an official and complete list of those killed during Qandy Qantar, including the circumstances of their death. Toregozhina said their request was rejected. The authorities said that court cases were still ongoing and referred to a previously published list compiled by the Prosecutor General’s Office, which was marred by errors, according to human rights activists.

Shormanbayev said human rights groups are now planning to file appeals to UN bodies regarding violations that Kazakhstan’s court system has failed to process. Some of the 50 cases that Shormanbayev’s NGO worked with were dismissed during the initial stages of the investigation.

“The cases of those who were killed are often dismissed before they reach trial. They simply say that there is no crime. This validates the shootings, that is, the state believes that the use of weapons was legal. The few cases that went on trial ended in the same way as the case of 4-year-old Aikorkem Meldekhan [who was shot to death on January 7, 2022]: The shooters always turned out to be innocent,” Shormanbayev told Vlast.

Shormanbayev’s International Legal Initiative will also file a final appeal in the case of the death of Zhasulan Anafiyaev. Seven police officers were accused of his death; they were charged with abuse of power with the use of violence and manslaughter.

“This cannot pass as torture, he was deliberately beaten to death. The perpetrators should have been tried under Article 99 – Murder,” Shormanbayev said, adding that he holds little hope of achieving justice in the Supreme Court.

“I am very dissatisfied with the work of the Supreme Court, they only treat cases formally.” Some of the most outrageous cases, according to Shormanbayev, ended with either lenient sentences or dismissals. “How many similar cases are being fought by lawyers throughout Kazakhstan, how many have not been investigated, how many have not been reported to the police due to pressure on the relatives of the victims?”

This paints a dark picture for Kazakhstan’s justice system.

“By international standards, Qandy Qantar cases show that the state has violated the right to life. That’s why I believe that all these cases should be monitored by the UN. I don’t believe the official information that only 238 people died. According to our research, corpses were removed from the morgues and many of the victims’ relatives were under pressure,” Shormanbayev said.

Shormanbayev also believes that the Qandy Qantar trials have been carried out only to confirm the government’s version of the events.

The tireless effort towards justice should not wane, Shormanbayev argued.

“We must record who shot, which judge, which prosecutor considered this case. One day the government will change and the guilty will answer for this. According to our Criminal Code, a mass shooting is considered a terrorist crime and there is no statute of limitations in such cases.”

Toregozhina also places faith in the future.

“Time will restore justice. These people will be rehabilitated, because the truth is on their side.”

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.